Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Europeans Sing Biomaterial Blues

Industry is losing out to North America and Asia on commercial manufacturing opportunities

by Alex Scott

October 20, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 42

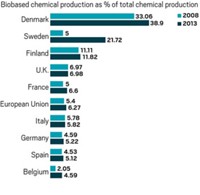

Leaders of Europe’s biobased chemicals industry spent time earlier this month comparing the progress of their sector with that of North America’s, and they didn’t like what they saw.

They were gathered for the annual European Forum for Industrial Biotechnology & the Biobased Economy (EFIB) in Reims, in the heart of France’s Champagne-Ardenne region. The perception among many of the executives was that innovations coming out of U.S. and European Union labs may be at a similar level but that North America is a better place to raise money and build commercial plants.

Still, the weeklong meeting in Reims, which featured about 600 delegates mostly from the biobased chemical sector in Europe, wasn’t completely glum, as there was plenty of optimism about the region’s future, not least from the emergence of a series of new companies.

“Don’t believe we are in exactly the same position as we were one year ago,” said a determinedly optimistic Stephan B. Tanda, a board member of the Dutch company DSM, at the closing of the conference. A $4.7 billion European Commission public-private fund for biomaterials plant projects that became available during the past year “is massive” for the sector, he said.

Tanda’s company is involved in a joint venture that manufactures commercial quantities of biobased succinic acid in Italy. But his upbeat message was not enough to convince a host of senior industry executives that Europe has everything in place to enable the shift from a fossil-fuel-based economy to one that is biobased. For example, some pointed out that of the $4.7 billion, the EC will contribute just $1.3 billion—and only if industry ponies up the rest.

What the EU is offering and what happens in reality “does not match up,” said Marc Verbruggen, chief executive officer of NatureWorks, a U.S. producer of a lactic acid-based biopolymer. He was clearly exasperated by his firm’s failed efforts to secure public funding for a European plant.

Barend Verachtert, deputy head of the biotechnology unit in the EC’s General Research & Innovation Directorate, was on the receiving end of comments such as those made by Verbruggen. Verachtert acknowledged that the EU needs to do better to ensure Europe is a suitable investment location for the biomaterials industry.

“The policy environment is not very stable or predictable. This is something we need to work on,” he said. In addition to providing financing, the commission is seeking to prepare the market by introducing measures including product certification and standardization, he said. Public-private partnerships between the EC and industry will play a role in the development of the sector and enable companies to get organized, Verachtert added.

But the EC’s pledges are too late for BioAmber. A producer of biobased succinic acid, it established a pilot facility in Pomacle, in Champagne-Ardenne, but has since begun building a commercial plant, set to open in early 2015, in Sarnia, Ontario.

The three key criteria involved in the decision to locate in Canada were the cost of the facility, the availability of feedstock, and financing, said Denis Lucquin, managing director of Sofinnova Partners, a Paris-based venture capital firm and an early investor in BioAmber. Financing considerations played a key role in the selection of the site in Canada, Lucquin said. Europe’s high cost of energy and limited availability of feedstock were further issues.

Discussing BioAmber was a tricky topic for representatives of agricultural cooperatives in Champagne-Ardenne seeking to attract biomaterials firms to the area. “We have learned a lot from BioAmber about providing a quicker response and putting public money on the table,” said a rueful Franck Mode, business adviser for CADev, the regional development agency for Champagne-Ardenne.

As home to a major sugar and starch refinery and to 1 million tons per year of biomaterial readily available as feedstock, the region is confident that—with the right financing in place—it can attract the big commercial projects of the future.

Others, though, cautioned that any improvement in the EC’s famous bureaucracy will be slow. “It takes several miles to turn around a supertanker,” says Anindya Mukherjee, president of i2i, a U.S.-based consulting firm specializing in technology development. The EC still has some way to go to mitigate financial risk for companies looking to establish biomaterials plants in the region versus the U.S. or Asian countries such as Malaysia, he said.

What Europeans do appear to be good at is launching start-up companies with novel biomaterials technologies. One such firm, France-based Stratoz, a spin-off from Montpellier University, told EFIB attendees about its process for recovering metals such as copper and cobalt from contaminated soils near mines using hyperaccumulator species of plants. The firm processes the leaves to produce catalysts for chemical synthesis.

The approach, developed by chemistry professor Claude Grison, has multiple environmental benefits, including soil remediation, avoidance of metals mining, and the option that some of the catalysts can be used in reactions without solvents, said Stratoz CEO Jacques Biton.

Other technologies showcased at EFIB included a process being developed by U.K. start-up Jellagen to convert a common jellyfish into medical-grade collagen. Jellagen plans to source jellyfish in U.K. waters and process them in Wales.

But even some of the most promising European biomaterials start-ups present in Reims, such as England-based Green Biologics, already are seeking to establish their manufacturing base outside Europe. Green Biologics is developing fermentation processes for making C3 chemicals, such as acetone, and C4 chemicals, such as 1-butanol, from C5 and C6 sugars using Clostridium microbes. The firm already manufactures 1-butanol through a partner in China and plans to open its first fully owned plant, in Little Falls, Minn., in 2016.

Despite the upbeat comments from Tanda and EC regulators, many of those at EFIB believe that Europe has serious work to do to ensure that its start-ups, as well as more mature companies, stay in Europe. EFIB attendees from European biomaterials firms might have been meeting in the Champagne region, but few were in the mood for popping corks.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter