Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Walmart And Target Take Aim At Hazardous Ingredients

Big retailers formulate policies to regulate the chemicals that go into the products they sell

by Melody M. Bomgardner

February 17, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 7

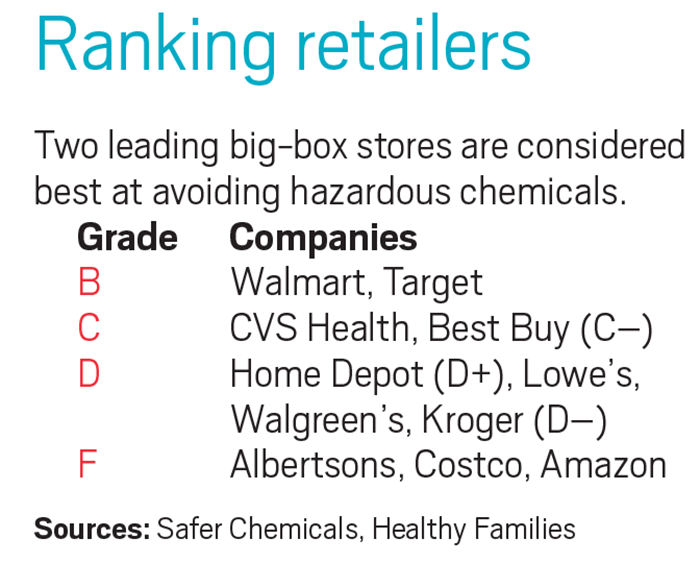

Megaretailers Walmart and Target announced last fall that they would reduce or eliminate ingredients in household goods that they deem harmful to human health and the environment. The policies, which focus on cleaners and personal care products, were applauded by advocacy groups that are pushing companies to disclose ingredients and apply more stringent safety criteria than required by law.

In the months since the announcements, both companies have gone silent about the policies. Neither Walmart nor Target agreed to speak with C&EN for this story. But interviews with executives and advocates who have worked with the firms on their strategies make it clear that the programs are still works in progress.

Although both retailers devised their approaches to respond to pressure from consumers, that is not the only driver, experts say. “The retail regulation you are seeing is a direct response to the failure of government to directly regulate those chemicals,” says Martin Wolf, director of product sustainability at Seventh Generation, a consumer goods company that focuses on environmentally friendly products. The proliferation of state chemical laws is another driver.

Walmart and Target plan to start their sustainable product odysseys by making it easier for consumers to find out what chemicals are present in products they carry. And they plan to assess the safety of products on the basis of their contents. But from there, their plans diverge.

Walmart has identified 10 high-priority chemicals to reduce, restrict, or eliminate, although it has not made this list public. Observers call this the “stick approach.”

Target is taking a “carrot approach.” It has devised a point system that will “reward” products that contain zero hazardous ingredients. Insiders say incentives could include desirable placement on store shelves. Whereas Walmart has identified 10 least-wanted chemicals, Target says it is going after compounds on several existing lists, such as the European Union’s list of “substances of very high concern,” which add up to more than 1,000 chemicals.

To some degree, Walmart and Target have taken their cues from state hazardous chemical laws such as those in California and Washington, says Joel A. Tickner, an associate professor of community health and sustainability at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. The laws require that consumer product makers and retailers disclose the presence of toxic ingredients. “The first step is just to know what is in the products you are selling,” Tickner points out.

At the same time, companies know that activist groups can send consumer products to labs for chemical analysis and then post the results online. Those chemicals can be compared to substances found in blood, breast milk, and cancer tumors. A company such as Revlon or Macy’s is just one social media campaign away from having a very bad day.

“Consumer awareness, online activism, people reading labels and asking questions—all of that is happening,” says Sarah Vogel, director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s environmental health program. EDF has worked with Walmart on an unpaid basis since 2005.

Walmart, no stranger to activist anger, began its effort to gather product information in 2008, when it began requiring suppliers to disclose sustainability information. To aid the effort, the company put together a consortium that includes consumer goods companies and advocacy groups. EDF even set up an office in Bentonville, Ark., where Walmart has its headquarters.

“Early on, we had conversations about identifying the chemicals in products,” Vogel recalls. The consortium examined tools that allow users to score consumer products using data on the human health and environmental effects of their ingredients.

However, consumer brand owners and their suppliers do not necessarily want to reveal their formulations for competitiveness reasons. And a system that tracks a small list of chemicals can quickly become outdated as more substances come under scrutiny.

Europe’s 2006 adoption of a program for the registration, evaluation, authorization, and restriction of chemicals, known as REACH, has made European retailers familiar with the slippery slope of chemical tracking.

Kingfisher, an England-based owner of hardware stores, began its implementation of REACH with a scorecard approach, says Paul Ellis, the company’s environmental regulation manager.

“We filtered down our product list to the 20% or so that may potentially have a chemical risk. Then we started to look to confirm that chemical content with suppliers,” Ellis says. “But often, suppliers don’t know precisely what’s in the products.” As the list of substances of concern expanded, the program became untenable.

“It’s okay when you have a small number of substances—we started with 14, then 20, then 40, then 60,” Ellis explains. “Now it’s 144, and we’re like, ‘Oh my God.’ We find ourselves going around in circles.” Now, Kingfisher is testing a new database that contains each product’s full bill of materials. It requires a computer model to estimate the likelihood that a material contains a substance of concern such as a particular plasticizer.

Walmart is likely to use its power as the world’s largest retailer to get suppliers to provide more complete product information. The company may build on a system developed by The Wercs, a compliance software firm, that it installed years ago to manage waste from its stores.

To populate the system, Walmart asked companies along its supply chain to input their chemical information, says Tom Carter, The Wercs’s vice president of strategic initiatives. For many companies, the request was a wake-up call.

“One Friday, a letter went out from Walmart to suppliers saying, ‘If your product contains chemicals, you have to log in to The Wercs and supply this very confidential information on Monday,’ ” Carter recalls. Suppliers were assured that the system would not disclose proprietary product information to Walmart. Rather, the store’s employees would use it only to generate waste-handling instructions. Still, “the day the letter went out, I think you could feel the ground shaking. It was a big deal,” Carter says.

The tool, called WERCsmart, is now being used by Target, CVS, and many other chains, Carter adds.

Walmart and the other retailers have an add-on tool called GreenWERCS to assess the health and environmental characteristics of all the chemicals in their suppliers’ formulations on the basis of any criteria, Carter says. But using corporate criteria, rather than legally mandated ones, requires a careful retailer strategy for working with the supply chain.

With the new policies, though, ingredients will soon have fewer places to hide. Walmart is requiring online public disclosure of ingredients by January 2015. And Target’s reward scheme devotes 20 points (of a possible 100) to public disclosure. Although cleaners and personal care products carry ingredient lists on their labels, some substances, such as phthalates used as fragrance carriers, do not appear.

Because Walmart and Target have built a great deal of flexibility into their policies, many unknowns still exist. Will brands be able to use generic terms such as “fragrance” that protect proprietary formulas? Are the alternative chemicals any safer? Which criteria will be nonnegotiable?

The retailers may choose criteria similar to that of green brands. Both have turned to Seventh Generation for advice, Wolf says. “We start with what we don’t want—carcinogens, mutagens, endocrine disruptors, neuro- and reproductive toxins. It’s a fairly clear statement of principle.” At the same time, he says, Seventh Generation stands up against unfounded public concerns about ingredients. For example, the firm has pushed back against Internet rumors that sodium lauryl sulfate can cause cancer.

Leading consumer brands including SC Johnson, Procter & Gamble, and Johnson & Johnson have already begun reformulating products and putting ingredient lists online. They have targeted substances including triclosan, phthalates, parabens, synthetic musks, and ingredients that form trace amounts of formaldehyde and 1,4-dioxane. J&J recently said its iconic baby shampoo, and all of its baby products, no longer contain formaldehyde or 1,4-dioxane.

Sustainability experts say retailers can also show leadership by making their own store-brand products safer. Walmart, for example, will begin to label store-brand cleaning products that comply with the Environmental Protection Agency’s Design for the Environment program, which restricts ingredients to chemicals judged to be safe by EPA.

Although many details remain a mystery, safe chemical policies from large retailers could have a major impact on how brand owners formulate their products, UMass’s Tickner anticipates. “Walmart is reaching far deeper in the supply chain, and people are listening,” he says, “because Walmart is Walmart.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter