Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Immediate Results

Case Study 3: Lonza helps Pharmacyclics quickly bring a cancer drug to market

by Michael McCoy

March 3, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 9

Near the end of the Nov. 13, 2013, press release announcing Food & Drug Administration approval of the cancer treatment Imbruvica (ibrutinib) is a short sentence: “Imbruvica is commercially available immediately.”

Winning FDA approval for a drug is a major achievement for any firm. Ensuring that the drug is immediately on hand in hospitals and pharmacies is almost as impressive. For that, Imbruvica’s developer, Pharmacyclics, can thank a 15-year partnership with Lonza, the contract manufacturer of the drug’s active ingredient.

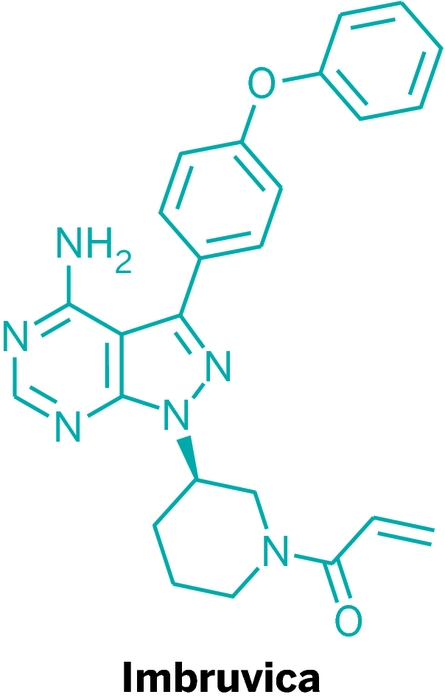

Imbruvica was approved to treat patients with mantle cell lymphoma, a rare and aggressive type of blood cancer diagnosed in about 2,900 people in the U.S. each year. Last month it was also approved to treat the most common adult leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Imbruvica works by inhibiting an enzyme, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, needed by cancer cells to multiply and spread.

COVER STORY

Immediate Results

It’s only the second drug to go through FDA’s breakthrough therapy pathway. Unveiled in July 2012, the pathway speeds up the review of drugs that may offer real improvement over available therapies for patients with life-threatening diseases.

Pharmacyclics submitted its New Drug Application to FDA for Imbruvica in late June 2013. Approval came quickly, in a little more than four months.

Pharmacyclics’ overall journey to market, however, was much longer. The company was founded in 1991 to develop porphyrins invented by Jonathan L. Sessler, a chemistry professor at the University of Texas, Austin. It went public in 1995.

Lonza entered the picture four years later when Pharmacyclics hired it to manufacture two porphyrin-like molecules: motexafin lutetium, in development to treat atherosclerosis, and motexafin gadolinium, for brain and lung cancers.

The picture got more interesting in 2007 when the investor Robert W. Duggan joined Pharmacyclics’ board. According to the Forbes 400 list of the richest Americans, on which Duggan is number 342, he was interested in Pharmacyclics because one of his sons suffered from brain tumors.

Imbruvica (ibrutinib)

\

Discoverer: Zhengying Pan

Mechanism of action: Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Years in development: Less than five

Approved: Nov. 13, 2013

Disease indication: Mantle cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Price: $130,000 annually for mantle cell lymphoma, $100,000 for chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Neither of the motexafins panned out. Notably, in 2007 Pharmacyclics received a nonapproval letter from FDA for the brain cancer treatment. The following year, Duggan staged a boardroom coup and took over as Pharmacyclics’ chief executive officer.

With Duggan at the helm, Pharmacyclics turned its attention to a family of oncology drug candidates it had licensed in 2006 for $2 million from Celera Genomics, which wanted to exit small-molecule drug development. One of the compounds, discovered by Celera chemist Zhengying Pan, was ibrutinib.

In February 2009, Pharmacyclics initiated its first clinical trial on ibrutinib and soon observed signs of efficacy and patient tolerability. Lonza was an obvious candidate to manufacture this compound in larger quantities, given its earlier work for Pharmacyclics, but Heow Tan, the drug company’s chief of quality and technical operations, says Lonza was by no means a shoo-in. Nonetheless, after evaluating multiple contractors, Pharmacyclics decided to stick with its old partner, Tan says.

Lonza, a venerable Swiss contract manufacturer, did for Pharmacyclics what it does for pharmaceutical firms big and small, notes Stephan Kutzer, head of Lonza’s pharma and biotech business. It took a chemical synthesis that was developed at small scale and turned it into one that could be run at large scale in a manufacturing plant.

“The project came to us as a raw lab-scale process, and our task, as always, was to scale it up for clinical production,” Kutzer says. This included improvements such as compressing reaction time, improving yield, streamlining raw material procurement, dealing with the products of side reactions, handling waste, and eliminating dangerous solvents.

And although the cost of manufacturing an active ingredient is usually small compared with what the finished drug sells for—Imbruvica costs $130,000 per lymphoma patient per year—Lonza’s goal is to streamline the process. It wants its customers to be prepared when their products eventually face competition from generics.

Tan is comfortable enough with Lonza’s expertise and his own team’s scale-up experience that he isn’t seeking manufacturing help from Pharmacyclics’ big pharma partner, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Biotech unit. In late 2011, the two agreed to codevelop and co-commercialize Imbruvica for oncology indications.

“We believe that, as a smaller company, we can sometimes move more nimbly compared with larger pharmaceutical companies,” Tan says. “In addition, we want to continue to build this kind of scale-up experience for our future pipeline products.”

Kutzer says he is focused on getting ibrutinib right and hasn’t spoken to Tan or others at Pharmacyclics about other products in its pipeline. But given Lonza’s key role in getting Imbruvica quickly to patients, the firm is sure to be on Pharmacyclics’ short list of manufacturing partners for the future.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter