Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

China Reduces Coal Use And CO2 Emissions, Boosting Global Climate Talks

Energy adjustments by world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter propels international negotiations

by Steven K. Gibb

April 27, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 17

China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, is claiming it significantly slowed both carbon dioxide releases and coal consumption in 2014. If confirmed and sustained, that trend could galvanize other countries’ climate change mitigation efforts as they prepare for upcoming treaty talks in Paris.

China’s CO2 emissions remained roughly flat between 2013 and 2014, according to Chinese government statistics and other sources, says Glen Peters with the Global Carbon Project, an international environmental research consortium that tracks CO2 emissions. The findings have surprised experts who watched China’s CO2 emissions nearly double over the past decade.

The Chinese government recently announced that 2014 saw a 2.9% reduction in coal consumption in absolute terms. The news follows years of double-digit annual growth: The 2002–12 period saw a 142% increase in coal burned in China, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Moreover, China’s largest coal producer, Shenhua Energy Co., projects a 10% drop in domestic coal sales from 2014 to 2015. These shifts could result in a substantial reduction in CO2 emissions given that China alone consumed a whopping 3.8 billion tons of coal compared with 4.3 billion in the rest of the world as recently as 2011, according to DOE.

Although it remains to be seen whether they can be sustained, these early indications of an absolute slowdown in China’s greenhouse gas emissions—combined with the country’s unparalleled investment of $90 billion in renewable energy last year—are encouraging to climate activists preparing for international climate talks set to conclude this December in Paris.

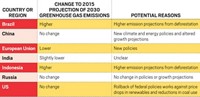

In November of 2014, China and the U.S. announced a bilateral climate agreement committing the U.S. to emitting 26 to 28% less CO2 in 2025 than it did in 2005. China pledged to peak its CO2 emissions by 2030 and then lower them. “That was a fantastic piece of diplomacy between two countries that represent the largest global emitters,” says Fabrice Vareille, head of the Transport, Energy, Environment & Nuclear Matters Section at the European Union’s office in Washington, D.C.

China appears to be well ahead of that promised pace. Climate concerns are one driver: Chinese officials recognize that their low-lying, densely urban coastal areas are some of the most vulnerable to sea-level rise and other anticipated impacts of human-caused climate change. Air quality is another driver, and China’s aggressive action to reduce dangerous concentrations of air pollution, such as particulate matter from burning coal, also carries climate benefits.

But observers say a confluence of other dynamics also helps explain the reductions.

The drop-offs are a result of strong policy mandates, a strategic shift to a service-oriented economy, and the slowing growth of China’s gross domestic product, or GDP, says Elliot Diringer of the Center for Climate & Energy Solutions, an advocacy group. He notes that those policy mandates include coal consumption caps in some Chinese provinces and the fact that a national cap is under consideration.

Climate scientists say there is inherent uncertainty in all nations’ CO2 emissions numbers. But U.S. climate experts say aggregate provincial emissions estimates may significantly depart from the top-down government numbers, warranting careful scientific review and confirmation.

Nevertheless, uncertainty over these emissions has not prevented environmental activists and the International Energy Agency (IEA) from heralding what they’re calling a “decoupling” of global economic growth and CO2 emissions.

Globally, CO2 releases from the energy sector were basically unchanged last year compared with 2013, the first time in 40 years that a halt or dip in these emissions wasn’t associated with an economic downturn, IEA says. China and developed nations such as Germany have encouraged investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency measures, and “for the first time, greenhouse gas emissions are decoupling from economic growth,” according to IEA.

But others say industrial growth and rising pollution levels are still considered to be strongly correlated. Former Chinese climate negotiator Xueman Wang, currently with the World Bank, says the economic transition to a service-based industry would be one key driver for maintaining GDP growth and lowering pollution. She adds that Chinese economists continue to debate optimal levels for annual GDP growth. “The arguments range from 4 to 8% because there is much uncertainty over the speed and success of managing China’s economic restructuring and rebalancing.”

Environmental advocates are praising China’s reductions even as they acknowledge that there are still unanswered questions. “China committed to peak its CO2 emissions by 2030, but it didn’t say at what level that peak would occur,” says Barbara Finamore of the environmental group Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), who bases her advocacy work in China.

The leveling off of coal consumption “augurs well for China’s ability to follow through. In fact, it indicates that such a peak could be achieved even earlier, which is good news for all those who are working for a meaningful climate agreement in Paris,” says Alden Meyer, director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists.

But China will face challenges in its efforts to sustain cuts in CO2 emissions. The World Bank’s Wang says China’s goal of sourcing 20% percent of its electrical power from nuclear plants and renewables by 2030 is based on some shaky assumptions. When this target was set, it included the planned construction of one new 1-gigawatt nuclear power plant every three weeks. Those plans are now on hold after Japan’s 2011 Fukushima nuclear plant disaster. China has “almost maxed out” hydroelectric opportunities, and would have to continue installing four 300-MW wind farms each week for 15 years to meet the renewables goal, she says.

Nevertheless, scholars say China’s actions to date are still impressive. “Showing that one of the world’s largest economies can turn around carbon dioxide emissions is a very exciting development as we head into Paris. It shows other rapidly developing countries that it is possible,” says atmospheric scientist Veerabhadran (Ram) Ramanathan of Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

U.S. officials and others say efforts to improve air quality are what is really driving changes in China’s coal consumption rates, with cuts in CO2 as a side effect. But even with dual benefits, the goal to peak emissions by 2030 will require strong and sustained leadership. “The only way to achieve these goals is a steady annual effort,” both in China and the U.S., says Jonathan Pershing, a senior adviser to the U.S. energy secretary and a former State Department climate change negotiator.

As for the talks leading up to and in Paris, some advocacy groups are predicting the negotiations will conclude with a successful treaty without a hitch. But others warn that significant work remains. For example, the World Bank’s Wang says the outcome of the talks may hinge on the validity of “very challenging and complex modeling efforts that must reliably make projections 15 years out.” The modeling is what countries must rely on to make commitments now to control greenhouse gas emissions in the future.

China’s move certainly gives momentum to the international talks. But the test is whether the treaty expected to emerge in Paris can deliver sufficient greenhouse gas controls to meet the goal policy-makers set more than a half-decade ago—preventing Earth from warming by 2 °C above preindustrial levels before 2100, if not sooner.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter