Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Hydrogel Helps Soft Materials Keep Up In 3-D Printing Craze

Materials: Water-logged matrix acts like liquid and solid to support printed structures made of polymers and living cells

by Matt Davenport

September 25, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 38

Researchers at the University of Florida, Gainesville, have developed a hydrogel matrix that acts as a solid support system for objects made with three-dimensional printing, yet the gel is almost entirely liquid (Sci. Adv. 2015, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500655).

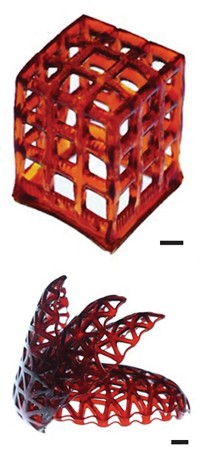

The team, led by Tapomoy Bhattacharjee and Thomas E. Angelini, has printed a variety of soft materials—such as polymers and living cells—inside this hydrogel to create arbitrarily complex structures that keep their shape. The hydrogel bolsters the ability of 3-D printers to create soft, functional structures, potentially including living tissue.

The gel contains microscopic particles made from a copolymer of polyaspartic acid and polyethylene glycol. But the copolymer accounts for less than 1% of the weight of the matrix, Angelini says. The rest is mostly water.

A 3-D printer’s nozzle can slip through the hydrogel as if the material were a liquid, but the particles are large and substantial enough to hold any printed material in place. “It’s like it’s trapped in a liquid without being able to sink,” Angelini tells C&EN.

“This is a beautiful piece of work,” says Jennifer A. Lewis, who was not involved with the study and has also developed novel support materials for 3-D printing with her group at Harvard University. She says what differentiates this granular hydrogel is its ability to flow back into place once the print nozzle passes through it.

The growing soft matter engineering team at the University of Florida now includes researchers from across campus who are working to print accurate polymer brain models that surgeons can use for practice and living human tumors for cancer research, Angelini says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter