Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

The Underlying Costs Of Research

Reimbursements for the overhead costs of facilities and administrative support for grant-funded inquiry are controversial and often misunderstood

by Andrea Widener

February 2, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 5

When most people count the costs of federal research, their first calculation is grants to individual scientists.

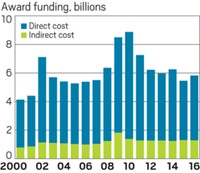

But when researchers get a federal grant, they are not getting money just to fund their research. A significant part of federal research funding goes to defray the infrastructure costs that underlie research. That reality sets up tensions among budget cutters in Congress, scientists who want more money for research, and administrators who are trying to cover costs.

Grants cover the direct costs of research, such as lab equipment, materials, and salaries for scientists and students they support. But the federal government also reimburses institutions for indirect costs, sometimes called facilities and administrative costs. These include what institutions shell out to heat and cool buildings, dispose of trash and hazardous waste, even shovel snow. Indirect costs also cover the teams of administrators many institutions say are now required to deal with the increasing number of regulations that are part of the research enterprise, from protection of human and animal health to reporting of financial conflicts of interest.

“Infrastructure costs are a necessary part of doing business,” explains David Kennedy of the Council on Governmental Relations, which studies the financial and regulatory aspects of government research.

Sally J. Rockey, deputy director at the National Institutes of Health, concurs, noting that the term indirect costs “is a bit of a misnomer. They are research costs.”

Although federal reimbursements for indirect costs may pay for necessary services, they are often a target for those who want to cut federal spending. Research institution leaders say that those attacks are unwarranted since most already spend significantly more on research support than the federal government pays for. The National Science Foundation estimates that in 2012 research universities shelled out a total of $15.9 billion in indirect costs for all grants, including $4.6 billion that they will never get back.

Indirect costs aren’t “something that universities have come up with to get more money from government. It is the only way we can recover any of these costs,” says Cynthia Hope, director of the Office for Sponsored Programs at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, and chair of the Federal Demonstration Partnership (FDP), a consortium that works to reduce federal administrative burdens.

Indirect Costs At A Glance

What are they? Also called facilities and administrative costs, indirect costs are the funds that research institutions spend in support of research grants. These include upkeep of infrastructure, such as lab maintenance, utilities, or library services. They also cover administrative support services such as grants offices and institutional review boards that grantees need to comply with government regulations.

Why does the government reimburse for indirect costs? Almost any institution that gets federal grants also receives funds for indirect costs as part of the government’s overall support for federal research. They are a particularly important issue for large universities and research institutions that get a lot of grant money. How much a research center gets is expressed as a percentage of a grant amount.

Who sets the rate for indirect costs? The rate is based on a review of a research institution’s actual costs. Each institution calculates a rate based on its financial data and then submits that rate to a federal agency for review. The Department of Health & Human Services reviews the information for hundreds of institutions. The Office of Naval Research conducts reviews for about 100 other institutions. Some smaller organizations, including the American Chemical Society, C&EN’s publisher, have their rate set by the National Science Foundation. The rate is usually updated every two to four years.

Why do research institutions get less than the rate negotiated with the federal government on certain grants? Research institutions get the full negotiated rate for most federal grants. But for some grants, federal agencies limit the amount that they will pay or require a contribution from the grantee’s home institution. For example, indirect cost reimbursements for training grants from the National Institutes of Health are capped at 8%. In addition, the amount of administrative fees that universities can collect has been capped at 26%. Congress can also set reimbursement limits.

SOURCES: Council on Governmental Relations, C&EN

When faculty members write grants, they know that the funders are paying an average of 50% above the cost of their research for indirect costs. Although many recognize that indirect costs are real, “the whole concern for indirect costs is made larger and exaggerated because there are fewer and fewer sources of grant funding,” says University of South Florida psychology professor Sandra L. Schneider, a faculty representative at FDP. If there are only so many federal dollars available, faculty wonder whether more grants might be available if indirect costs were lower. Successful grant recipients might also be concerned they are paying more than their share of facilities costs.

Without some way to pay for infrastructure, though, many centers wouldn’t be able to sustain their federal research programs, observers say. “You have a national interest in undertaking this research. How do you figure out an appropriate way to allocate the costs?” asks Howard Gobstein at the Association of Public & Land-grant Universities.

The current arrangement evolved in the 1960s, when it became clear that different institutions were getting different and arbitrary amounts to support their scientists, Gobstein says. The idea was to create a system that would reimburse research centers for their actual costs of supporting federal research.

To do that, institutions examine their actual costs of supporting research, as outlined by the White House Office of Management & Budget (OMB). They turn that figure into a percentage of funding that they say should be tacked onto each federal grant their researchers receive. This is called an indirect costs rate.

Some people in the science community seem to think that indirect costs rates are arbitrary, says Susan Sedwick, associate vice president for research at the University of Texas, Austin, but that’s not true. “There is a very stringent methodology we have to go through to set those rates.”

The research institutions submit a proposed rate to either the Department of Health & Human Services or the Office of Naval Research. Then a back-and-forth consultation begins between the institution and the government agency. “It’s called a negotiation, but what they are doing is analyzing the rate,” explains Paul Calabrese, a consultant with Rubino & Co. who works with nonprofits to help them develop their indirect costs rate.

The federal reviewers scrutinize the underlying details of the proposed rate. These include specifics about a variety of costs from an increase in utility prices to the need for additional administrative personnel.

That negotiation eventually results in a final indirect costs rate, which is good for between two and four years. The final rates vary significantly based on the costs in a particular geographic area. A recent analysis by the journal Nature showed that the top rates go to facilities in expensive urban centers, such as Boston.

The rates also differ based on type of research institution. Nonprofit research organizations and hospitals have the highest rates, in part because their primary goal is research.

“Universities’ primary reason for being is for education, and the state supports that or tuition supports that,” explains James Paulson of Scripps Research Institute California. “At a private research institution, the costs of doing research are the same, but there aren’t those other supports.”

Even with high indirect costs rates—Scripps gets 89.5%—“it is not possible to run an institution completely on grants” from the federal government, Paulson says. Institutions need other sources of revenue, such as partnerships with companies, donations, and intellectual property revenues.

One reason for this situation is that not all federal grants pay the full indirect costs rate. Most NIH, Department of Defense, and National Science Foundation grants to individual scientists now pay the full rate. But grants for training and early-career scientists or grants that agency program officers believe require local support, like partnerships with companies, are less likely to pay all of a research institution’s costs. New rules implemented by the White House last year require an agency’s director to issue a written exception if a research institution’s full costs aren’t covered.

State governments and philanthropic foundations, some of which pay no infrastructure costs, are a particular problem. As a land grant institution, “we do a lot of projects for the state. That limits us,” explains Robert Dixon at Oklahoma State University.

The problem has gotten bad enough that some research institutions are asking their scientists to apply primarily for grants that pay the full indirect costs rate. In the past, state funds or tuition costs might have made up the difference, FDP’s Hope explains, but “over the years we did ourselves a disservice by saying that it wasn’t important to recover all of the costs.”

Another problem for universities is that in the 1990s Congress capped the amount of administrative costs they can recover at 26%. Meanwhile, the administrative burden for grants has grown. “It is a moving target,” explains Daryl Weinert at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “New regulations get added every few years, and you’re adding on new systems to comply with them.”

There is some effort under way to scale back federal-grant administrative burdens. But with federal budgets strained, “I don’t think there is any momentum at this point to change that,” NIH’s Rockey says.

That won’t stop universities from doing research. “We would like to recover more costs, but we aren’t going to quit doing research,” says Michael F. Malone at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. “We do have shared goals. It is just a matter of how much it costs to achieve them.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter