Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Seventh Row Of The Periodic Table Is Now Complete With Addition Of Four Elements

Nuclear Chemistry: IUPAC gives its stamp of approval and will issue a new table

by Jyllian Kemsley

January 7, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 2

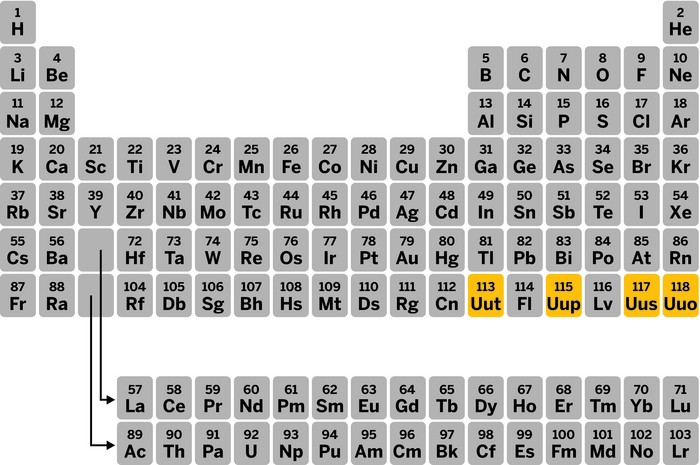

With the addition of four new elements, the seventh row of the periodic table is officially full, the International Union of Pure & Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) announced on Dec. 30.

A joint committee made up of IUPAC and the International Union of Pure & Applied Physics gave its stamp of approval, and IUPAC temporarily gave element 113 the name ununtrium (Uut), 115 the name ununpentium (Uup), 117 the name ununseptium (Uus), and 118 the name ununoctium (Uuo).

.@helenarney extends Tom Lehrer's chemical element song with today's 4 new ones.https://t.co/Pmyd693y9x

— Jon Snow (@jonsnowC4) January 4, 2016

The people credited for first discovering an element get the right to propose a permanent name and symbol. For element 113, that honor goes to scientists at Japan’s RIKEN research institution. It will be the first time that Asian researchers name an element.

For the other three elements, credit and naming rights go to European-American collaborations involving Russia’s Joint Institute for Nuclear Research and the U.S. Lawrence Livermore and Oak Ridge national laboratories.

IUPAC plans to issue a new periodic table with the four added elements and other updates by the end of January, says Lynn M. Soby, IUPAC’s executive director. She hopes that the elements will receive their final names in about six months, at which point IUPAC will again update the table.

What fascinates researchers about superheavy elements in the seventh row and beyond is their potential chemistry, says Dawn Shaughnessy, principal investigator for the Heavy Element Group at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. As the number of protons in an atomic nucleus increases, electrons speed up and generate relativistic effects that alter orbital energy levels. That could mean that group reactivity trends don’t hold as elements get heavier.

But doing chemistry on short-lived atoms created one at a time in heavy-ion accelerators is challenging. “The periodic table says that 118 is a noble gas. How could we determine that based on a single atom?” Shaughnessy asks.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter