Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Fixing Iron Levels In Lung Cells Could Treat COPD

Drug Development: Study shows that concentrations of the metal inside cell organelles increase in mice with the disease

by Michael Torrice

January 14, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 3

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—a group of disorders that include chronic bronchitis and emphysema—struggle to breathe and rely on drugs called bronchodilators to widen their obstructed airways. But these drugs just relieve symptoms of COPD and don’t stop the underlying mechanisms that cause this progressive disease.

A new study reports a possible COPD mechanism in which iron levels in the mitochondria of lung cells are elevated, damaging the critical cellular powerhouses. A small molecule capable of sequestering iron restored proper levels of the metal, preventing, and even reversing, lung inflammation and injury in a mouse model of COPD (Nat. Med. 2016, DOI: 10.1038/nm.4021).

Although smoking is the number one risk factor for COPD, scientists have identified genetic factors that make people susceptible to the disease. One such gene codes for iron-responsive element-binding protein 2 (IRP2).

Augustine M. K. Choi of Weill Cornell Medical College and his colleagues wanted to understand how this protein is involved in the disease.

The team studied mice that had spent two hours per day for up to six months in a chamber filled with cigarette smoke. Normal mice developed a COPD-like disease, but mice genetically engineered to lack the IRP2 gene did not.

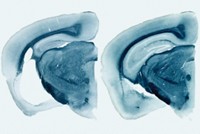

When the researchers studied the mitochondria of COPD mice, they found that the organelles were dysfunctional and damaged. In particular they had elevated levels of one form of cellular iron.

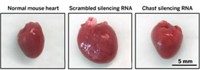

Normal mice that were given deferiprone, an FDA-approved iron-chelating drug, and then exposed to cigarette smoke didn’t develop the COPD-like disease. In animals that had already developed the disease, the drug improved symptoms and lowered mitochondrial iron levels.

Peter J. Barnes, head of respiratory medicine at Imperial College London, says the researchers next need to show that this mechanism is relevant in people. “Mice can be misleading in the context of COPD,” he says. “All mice exposed to cigarette smoke get COPD, while not all humans do.” Barnes suggests investigating whether mitochondrial iron levels are disrupted in COPD patients.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter