Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

A decent first half for pharmaceutical firms

New products give, patent expirations take away, but results overall are up

by Ann M. Thayer

August 21, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 33

Pricing scrutiny, competition from generics, and mergers remain stress factors for the pharmaceutical industry. Nonetheless, drug companies are finally seeing some improvement in their finances. After a few years of decline, major companies saw combined sales and earnings grow more than 5% in the first half of 2016.

The results are telling in other ways too. C&EN has stopped dividing the 18 companies it tracks into pharmaceutical and biotech groups because the distinction has blurred. Companies such as Amgen and Biogen that began life as hot start-ups focused on biologics now rank among the top drug firms in terms of sales, earnings, and, notably, profitability. At the same time, sales and earnings growth rates for many of these firms have cooled and are now more in line with traditional pharmaceutical companies.

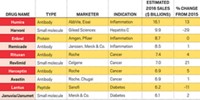

The top-selling drugs have also evolved and are now a mix of small molecules and biologics. Leading products from big pharma, which was historically associated with small-molecule drugs, are increasingly biologics. At the same time, the top drugs from so-called biotechs Celgene and Gilead Sciences are small molecules. Most drug firms are taking the middle ground, calling themselves “biopharmaceutical” companies.

One adopter of this term is AbbVie, whose industry-leading drug Humira is an antibody approved for treating at least a half-dozen inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. In the first half of this year, sales of Humira rose 17% to exceed $7.7 billion. Accounting for more than 60% of AbbVie’s sales, Humira helped the firm post its sixth consecutive quarter of double-digit sales and earnings growth at the end of June.

But as Humira faces more direct competition, AbbVie will need new products to continue growing. In July, a Food & Drug Administration advisory panel recommended that the agency approve Amgen’s biosimilar version of Humira. FDA often accepts such panels’ recommendations, and Amgen is preparing a launch later this year. AbbVie, which claims to have patents that protect Humira from competitors until at least 2022, has just filed a lawsuit to block Amgen.

At the same time, AbbVie is building its overall business with regulatory approvals for the leukemia drug Venclexta, which is partnered with Roche, and the multiple sclerosis therapy Zinbryta, which it is launching with Biogen. AbbVie also spent $5.8 billion up front, and potentially $4.0 billion more, to acquire Stemcentrx and its five clinical-stage cancer therapies, including the antibody-drug conjugate Rova-T.

Whereas Humira sales have been rising steadily over more than a decade, during the past few years Gilead has been introducing drugs whose sales vault rapidly to mega-blockbuster status only to quickly drop as the firm launches a follow-on product. This year, however, that didn’t happen. Instead of the nearly 40% growth Gilead posted in the first half of 2015, the firm’s sales fell about 2%. Earnings dropped about 11%.

Gilead’s first-half sales of hepatitis C drugs were down 12% to $8.3 billion, largely because of a 22% drop in sales of Harvoni, which in late 2014 had been the follow-on to 2013’s Sovaldi.

The company said Harvoni saw little impact in most markets from competitors Zepatier from Merck & Co. and Viekira Pak from AbbVie. Instead, Gilead attributed declining sales to fewer new patients, higher rebates, and lower revenue per patient. It anticipates a gradual decline in new patients going forward, especially in mature markets such as the U.S., Germany, and France.

But a new hepatitis C drug from Gilead is coming. At the end of the second quarter, FDA approved Epclusa, a combination product that can be used against any hepatitis C virus genotype. Gilead, which has come under fire for the prices of its drugs, will charge about $75,000 for a course of Epclusa, compared with $84,000 for Sovaldi and $94,500 for Harvoni.

Gilead also launched a new drug called Genvoya in the HIV area, which accounts for about a third of the firm’s sales. Sales of Genvoya, a product that combines four drugs in a single pill, more than doubled in the second quarter and reached $460 million for the half-year mark. Genvoya is quickly becoming the most widely prescribed HIV regimen for new patients. It’s also gaining ground as patients switch from Gilead’s Atripla and Stribild.

Meanwhile, new HIV products also helped boost sales and earnings at GlaxoSmithKline. Its half-year sales in the HIV area increased 50% to $2.1 billion, driven by Triumeq and Tivicay. Triumeq, the first single-tablet regimen not from Gilead, has been helping increase GSK’s share of the market, according to an analysis by Thomson Reuters Cortellis. The drug is expected to generate sales of $4 billion in 2020.

“The improved longevity of HIV-infected patients and widening of the antiretroviral eligibility criteria are expanding the size of the already-large HIV market,” Thomson Reuters says.

Gilead’s first-generation HIV products contain tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which is set to lose patent protection in July 2017. The entry of generic TDF will make all-generic anti-HIV regimens a possibility. But Gilead is prepared for this: Genvoya and the firm’s other new drugs use tenofovir alafenamide fumarate instead of TDF.

Generics competition continued to plague sales and earnings at other pharma companies, including AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sanofi. In the second quarter, Novartis faced the first months of generics competition for its cancer drug Gleevec. For AstraZeneca, however, losses to generics might soon be offset by new oncology products.

Similarly, oncology products contributed to double-digit sales and earnings growth at Bristol-Myers Squibb and Celgene. BMS continues to amass regulatory approvals and strong sales—$1.5 billion in the first six months of the year—for its PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor Opdivo. The antibody drug competes with Merck’s Keytruda. Both have been approved in multiple cancers and are in clinical testing for many more.

But Opdivo is not unstoppable. Earlier this month, the antibody therapy failed in a late-stage clinical trial to be effective alone in patients with previously untreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. The news sent BMS’s stock into a steep decline.

Oncology and cystic fibrosis (CF) are key markets for Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Sales of its two approved CF drugs, Orkambi and Kalydeco, jumped 172% in the first half. Their combined $830 million in sales also helped the company turn a profit. Vertex predicts that Orkambi sales will hit $1 billion this year and Kalydeco will reach about $700 million.

Another relatively small company, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, has 15 product candidates in clinical development, including 14 monoclonal antibodies. Seeking more candidates, Regeneron in April paid $75 million up front to work with the CRISPR/Cas9-based drug firm Intellia Therapeutics. For now, the company is strongly reliant on sales of the eye drug Eylea.

Regardless of their size, pharmaceutical firms continually strive to improve their R&D productivity and expand their pipelines. For example, Shire’s acquisition of Dyax in January and Baxalta in June brought about a major jump in its first-half sales and earnings.

Sanofi, meanwhile, has been trying for months to acquire Medivation. It is willing to spend more than $10 billion for a company whose lead product, the prostate cancer drug Xtandi, is on track to have annual sales of about $2 billion. But many other potential acquirers—including AstraZeneca, Celgene, and Pfizer—have reportedly stepped forward.

For Pfizer, it was the late-2015 acquisition of Hospira that provided a double-digit boost in sales and earnings this year. Excluding the Hospira contribution, Pfizer’s sales would have risen only 5%.

But the news most anticipated from Pfizer is not about another acquisition—in April it dropped a $160 billion plan to buy Allergan and in June spent $5 billion to buy the boron chemistry firm Anacor Pharmaceuticals—but whether it will decide to split into two separate companies. Speaking to analysts on a conference call last month, Chief Executive Officer Ian Read said the decision has yet to be made.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter