Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Coatings

Names for elements 113, 115, 117, and 118 finalized by IUPAC

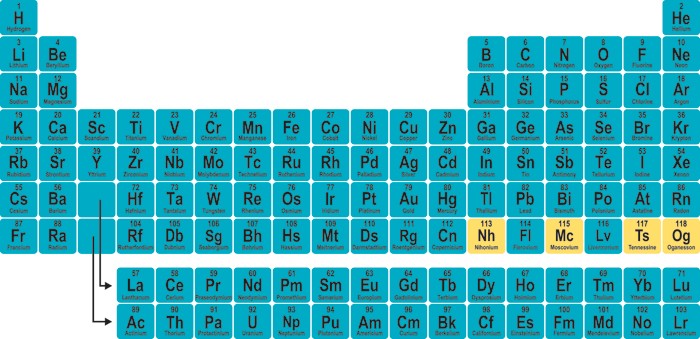

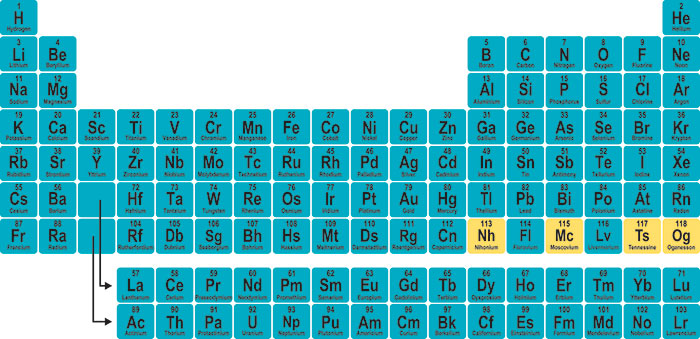

Nihonium, moscovium, tennessine, and oganesson complete the seventh row of the periodic table

by Jyllian Kemsley

November 30, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 48

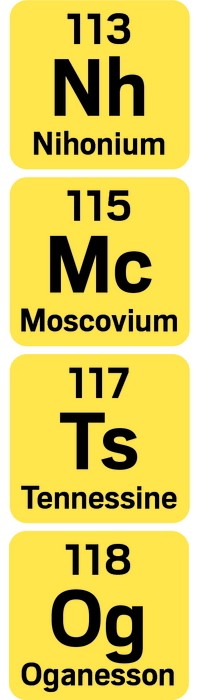

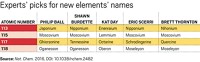

Nihonium, moscovium, tennessine, and oganesson are the permanent names for elements 113, 115, 117, and 118, the International Union of Pure & Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) announced today.

IUPAC officially recognized the elements at the end of 2015.

The discoverers of new elements get to propose names and symbols. Japan’s RIKEN research institution named nihonium (Nh). Nihon is one of two ways to say “Japan” in Japanese.

European-American collaborations involving Russia’s Joint Institute for Nuclear Research and the U.S. Lawrence Livermore and Oak Ridge national laboratories named moscovium (Mc), tennessine (Ts), and oganesson (Og). Moscovium and tennessine recognize the Moscow and Tennessee areas, respectively. Oganesson honors Russian nuclear physicist Yuri T. Oganessian, who leads the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research

The endings of the four names conform to the naming traditions of their respective periodic table groups.

After revealing the proposed names in June, IUPAC accepted public comments on them for five months. An upcoming paper in Pure & Applied Chemistry about the names and symbols notes that chemists raised concerns about possible confusion regarding the symbol for tennessine, Ts, which is also used as an abbreviation for the tosyl group (p-toluenesulfonic acid). “Other symbols such as Ac (element 89) or Pr (element 59) are also used by chemists as abbreviations for the acetyl and the propyl groups, respectively,” the paper says. “Any chemist would be able to discriminate between the different meanings from their contexts, and therefore there was no need to sacrifice the name proposed by the discoverers.”

“Overall, it was a real pleasure to realize that so many people are interested in the naming of the new elements,” says Jan Reedijk, a chemistry professor at Leiden University and president of IUPAC’s inorganic chemistry division, in a press release. He adds that even high-school students wrote IUPAC essays about possible element names, noting how proud they were to participate in the process.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter