Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Neuroscience

Cancer Drug Could Help Binge Drinkers

Neuroscience: Mouse study suggests an enzyme often associated with cancer could be a new target for alcohol abuse

by Michael Torrice

January 27, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 5

There are only a handful of drugs approved by the Food & Drug Administration to help people with alcohol abuse disorders control how much they drink. The drugs have limited effectiveness, and one, disulfiram, works by making people ill when they consume alcohol. This has led some neuroscientists to look for better therapeutics.

Researchers at the University of Illinois, Chicago (UIC), report they may have found a new target for alcohol abuse—an enzyme previously linked to cancer. They demonstrated that a recently approved drug that inhibits the enzyme reduces binge drinking in experiments with mice (Addict. Biol. 2016, DOI: 10.1111/adb.12358).

The target is anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). UIC professor Amy W. Lasek and others previously found that variations in the ALK gene have been associated with alcohol dependence and heavy drinking in people.

But most scientists have studied ALK because changes to its gene can cause cancer. FDA has approved three ALK inhibitors to treat certain lung cancers, most recently giving its stamp of approval to Genentech’s alectinib.

Lasek and her colleagues tested alectinib in mice that binge drink. The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism defines binge drinking in people as consuming enough alcohol in about two hours to increase a person’s blood-alcohol concentration above 0.08% by mass—that’s about five drinks for men, and four for women.

To create a similar situation for the mice, the researchers replaced the animals’ water with a 20% ethanol solution for two or four hours during the time when the mice were most active. The team used a type of mouse known to enjoy a stiff drink. “This mouse will drink in two hours enough alcohol to get intoxicated,” Lasek says.

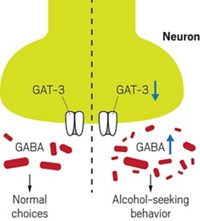

Mice treated with alectinib drank significantly less alcohol than those that didn’t get the drug. The inhibitor didn’t reduce consumption of all beverages, though: The treated mice continued to guzzle a sugary solution—a drink they also really enjoy—to the same extent as untreated animals, suggesting the drug was acting on a pathway in the brain affected by alcohol.

The researchers think the ALK inhibitor regulates alcohol consumption by changing how neurons act in the brain’s reward center, which generates motivation and reinforces behaviors.

Todd E. Thiele, who studies the neurobiology of addiction at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, is excited that alectinib has already gone through clinical trials for another indication. That means there are already safety data for it in people, a fact, he says, that could help ease the drug’s path to clinical testing for alcohol abuse disorders.

Lasek says her team plans to next test alectinib in mice that have become dependent on alcohol to see whether ALK could serve as a target not just for binge drinking but also for alcoholism. Clinical tests would be needed to determine whether the results translate to humans.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter