Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

NOBCChE cultivates young scientists

Annual conference nurtures growth of black chemists and chemical engineers

by Jeff Huber, special to C&EN

January 9, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 2

As soon as Murrell Godfrey heard mention of Cameroon, a lightbulb turned on in his head.

The director of the forensic chemistry program at the University of Mississippi was talking with Kelly Njine Mouapi, a graduate student at the University of Louisville, at a social event during November’s annual meeting of the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists & Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE, pronounced no-buh-shay). When Mouapi said she was from Cameroon, Godfrey immediately remembered meeting another Cameroonian earlier during the conference. He then scanned the room, found the person he was thinking of, and walked Mouapi over for an introduction.

Elizabeth Ndontsa, a postdoc at the University of California, Berkeley, was happy to be approached. And she became even happier when she learned about all the commonalities she shares with Mouapi. As the two discovered, not only are they both female scientists who grew up in Cameroon, but they’re also both biochemists focused on the study of proteins. And with Mouapi exploring postdoc opportunities at places such as Scripps Research Institute California, where Ndontsa’s lab was previously located, Ndontsa had contacts and firsthand experience to pass along.

NOBCChE goes to court

The verdict is in: One of the highlights of NOBCChE 2016, held Nov. 7–12, was a mock crime scene and trial that showcased the role science plays in forensics.

For the mock crime scene, Murrell Godfrey, director of forensic chemistry at the University of Mississippi, taped off a section of the conference’s exhibition hall. There, NOBCChE attendees could view a silhouette of a dead body, blood spatter, spent gun cartridges, a gun, and drug paraphernalia.

The scene then formed the basis of a mock trial in which NOBCChE attendees role-played different figures from a court proceeding. Venroy Watson, a Ph.D. candidate in chemical engineering from Florida A&M University, played the defendant, who was accused of homicide and possession of a controlled substance. Ann-Elodie Robert, an undergraduate chemistry major at the University of Pittsburgh, played the defense attorney. Maureen Craig, a chemist with the Drug Enforcement Administration, played the prosecuting attorney. Darrell Davis, a retired DEA lab director, played the judge. Godfrey served as the bailiff. And the audience in attendance acted as the jury.

During the trial, a few preselected NOBCChE attendees approached the stand pretending to be forensics experts who had been called to testify about their crime scene analysis. One expert testified on how gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy were used to identify cocaine at the crime scene and on the defendant. Another spoke about how inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry helped match gunshot residue left at the crime scene to residue found on the defendant. And other expert witnesses explained how fingerprint and DNA analyses confirmed a match between the defendant’s fingerprints and blood and those found at the crime scene.

This marked the first time that NOBCChE had ever hosted a mock crime scene and trial, Davis told C&EN following the proceedings. Previous NOBCChE workshops had focused on forensics activities in the field and in the lab, he said, so it made sense to showcase how those activities ultimately lead forensics experts to participate in the judicial system.

Attendees appreciated the insight. The mock trial “gave me a new perspective on how scientists represent themselves in court,” said Chelsey Lamar, a chemistry graduate student at the University of Maryland, College Park, who also serves as vice president of that university’s NOBCChE student chapter. “You need to represent yourself and just state the facts and not try to agree or disagree with who is being prosecuted.”

Later, reflecting upon the similarities she and Ndontsa possess, Mouapi couldn’t believe her luck. “She’s in biochemistry. She’s a black woman scientist. It’s just amazing,” Mouapi enthused. “It’s too much of a coincidence, and I’m happy about it—really happy about it.”

The coincidence might have flabbergasted Mouapi, but Godfrey, chair of NOBCChE’s southeast regional section, appeared less surprised by the encounter. As a NOBCChE veteran who attended his first conference in the late ’90s and has returned to the annual meeting every year since, Godfrey can personally attest to the feeling of camaraderie and community that pervades the conference. At NOBCChE, he explained, “we’re about family and bringing people together from all walks of life.”

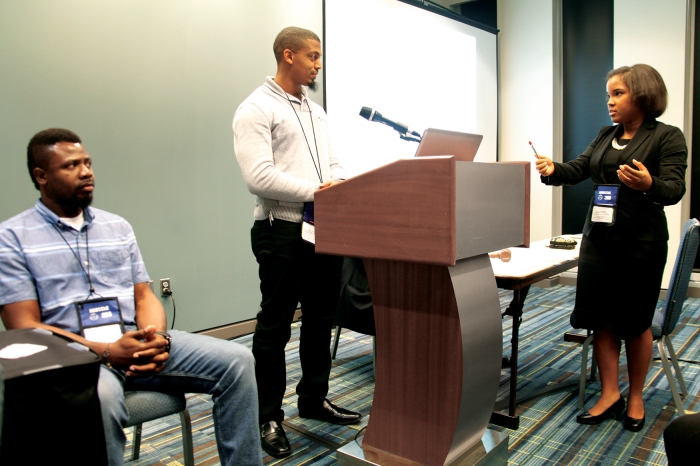

The 2016 conference, held in Raleigh, N.C., was no exception, bringing together hundreds of minority chemists and chemical engineers. It was an opportunity to reconnect with old friends, meet new ones, and participate in an array of activities including a career fair, research symposia, and professional development sessions that fell under the conference theme of “Paradigm Shift: Cultivating STEM Leadership to Solve Grand Challenges.”

This commitment to developing leaders in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics was established right from the start of the conference during the opening luncheon, which is named after Winifred Burks-Houck, NOBCChE’s first female president. Presenting the lunch’s honorary lecture, Tashni-Ann Dubroy, president of Shaw University, described the long and winding road that led her to eventually become the second-youngest person to serve as Shaw’s president—a journey that included growing up in Jamaica, stints in industry and academia, and the founding of the hair care company Tea & Honey Blends and the Brilliant & Beautiful Foundation for mentoring women in science.

“Who is going to follow this young girl who came from Jamaica, who had a big dream, and who’s been able to experience so many things in life at such a young age?” Dubroy asked as she looked at the crowd of conference attendees before her. “The answer is that it’s you. We’ve got to cultivate you.”

To foster this spirit of encouragement, the conference hosted several educational workshops, including one focused on entrepreneurship led by Nicholas H. Oberlies, a chemistry professor at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and his business partner Cedric Pearce, chief executive officer of the natural products firm Mycosynthetix. Oberlies and Pearce talked about how their respective backgrounds in academia and industry helped them found companies that work to translate basic science discoveries into commercial projects.

“Don’t be afraid of entrepreneurship,” Oberlies told the workshop’s audience of undergraduate and graduate students. “I guarantee you that if you know how to solve a structure from an NMR spectrum, or look at a mass spectrum, or you know what IR stands for,” he said, “you can figure out the business stuff. But it takes a little bit of a different mind-set and a little bit of guts.”

That message resonated with Jalisa N. Holmes, a Ph.D. candidate in chemistry at Georgia State University, who attended the workshop. “Hearing these guys, knowing that they came from other positions before starting their own businesses, lets me know that it’s possible” to launch my own start-up, she said.

Such empowerment being instilled into NOBCChE attendees is exactly why Karelle Aiken, a chemistry professor at Georgia Southern University, made it a point to bring students with her to the conference. Since helping to organize a NOBCChE student chapter at her school in 2008, Aiken has encouraged many to attend the conference and present their research. She said she does this because the opportunity augments the support that students are already receiving from Aiken and her colleagues.

When students are at school, Aiken said, “they don’t take us seriously when we say, ‘You’re doing a good job.’ ” But all that changes when representatives from academia and industry approach students presenting research at NOBCChE and recognize their hard work. “It means so much more to them,” Aiken explained.

Just as impactful, Aiken continued, is the effect that walking into a conference full of minority scientists can have on students’ resolve and determination to complete their studies and earn their degrees. For instance, Aiken remembers the first time she ever brought a group of students to NOBCChE. “They had never been in a room where the majority of the scientists looked like them,” she said. “It took them from ‘I’m really trying to do this’ to ‘Oh, I belong in STEM.’ ”

Kwaku Kyei-Baffour, a Ph.D. candidate in organic chemistry at Purdue University, said he could relate to discovering that sense of belonging at NOBCChE. Born and raised in Ghana, Kyei-Baffour noted that “there are not so many Africans or black Americans in the program” at Purdue. But after attending NOBCChE for the first time this past November, he was pleasantly surprised to meet other chemists from Ghana. “I thought I was more alone in this country being a Ghanaian here doing chemistry,” he said, but “I’ve met so many Ghanaians” at NOBCChE.

Those encounters clearly left a positive impression on Kyei-Baffour because, later, when asked whether he plans on coming back to NOBCChE again in the future, the young organic chemist didn’t hesitate in his response. “Definitely,” he said.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter