Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Jupiter is a big old planet

Chemical clues in meteorites provide new insight into planet’s age

by Matt Davenport

June 19, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 25

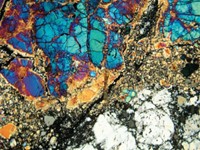

Jupiter is a case study in solar system superlatives. The gas giant is the biggest planet orbiting the sun, it’s the most massive, and new evidence suggests it’s also the oldest (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1704461114). Using mass spectroscopy, researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the University of Münster observed that Earth’s iron meteorite samples cluster into two groups: those that are enriched in heavier isotopes of tungsten and molybdenum and those that aren’t. These data suggest that the solar system once had two distinct reservoirs where meteoric material amassed. Something must have kept these reservoirs separate, and a baby Jupiter, roughly 20 times the mass of Earth, is the likeliest explanation, say researchers led by Livermore’s Thomas S. Kruijer. On the basis of the ages of the dichotomous samples, the team posits that Jupiter’s birthday was about 1 million years after the formation of the solar system. That’s within the predicted age range of Jupiter, but at its oldest end. Jupiter continued growing after its formation and eventually became massive enough to help stir up the reservoirs. Today, billions of years later, meteorites still carry clues that chemists can study to learn about the early solar system.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter