Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Slug mucus inspires possible surgical glue

Material sticks more strongly to wet tissues than commercially available medical adhesives do

by Michael Torrice

July 27, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 31

To help cling to leaves and other surfaces, some slugs secrete a sticky mucus. Engineers have used this slug secretion as inspiration to develop a synthetic adhesive that is significantly stronger than commercially available surgical glues (Science 2017, DOI: 10.1126/science.aah6362).

“It’s a really elegant and creative design to make tough adhesives that work in wet environments,” says Mark W. Grinstaff of Boston University, who was not involved in the work.

To close up wounds or surgical incisions, doctors sometimes reach for glues to hold tissues together. But sticking something to flesh can be tricky because biological tissues are wet and oddly shaped, and they move, says David J. Mooney of Harvard University.

Mooney and his colleagues came across a paper analyzing the material properties of mucus from a type of slug (Arion subfuscus). The sticky mucus has two components: polycations that help the mucus adhere to surfaces through electrostatic interactions and covalent bonding, and a tough matrix that absorbs and dissipates stress. This combination allows the slug to stick strongly to a surface by resisting forces—such as those from wind, rain, or the beak of a hungry bird—that could dislodge it.

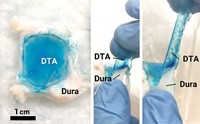

To mimic this design, Mooney’s team created a stress-dissipating matrix from cross-linked polymers, polyacrylamide, and alginate. The researchers then coated the matrix with the polycation chitosan, which inserts itself into the matrix and produces an adhesive surface. “It’s an example of simple elegance,” how the team put together already available materials in a new way to solve a problem, says Jennifer Elisseeff, a biomedical engineer at Johns Hopkins University.

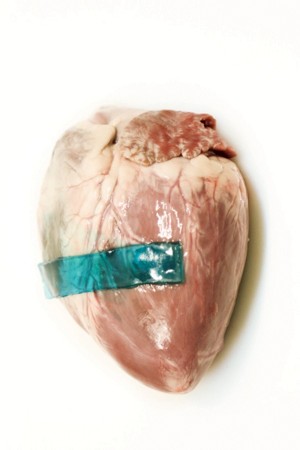

The researchers tested the adhesive on pig skin, liver, heart, and cartilage and found that it was stronger than both cyanoacrylate (superglue) and a surgical sealant called CoSeal. The experiment that most impressed Grinstaff was one involving a wound on a liver. “Getting the liver to seal and stop bleeding is currently a big clinical problem,” he says. “There are no good adhesives for that application today.”

Mooney’s team is testing the material further to optimize its properties and determine which medical applications it is suited for.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter