Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Newscripts

Spirals, spinners, and science

by Corinna Wu

August 7, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 32

Whorl watching

Staring at a rotating spiral pattern produces a hypnotic effect; the pattern seems to either expand or contract, depending on the direction of rotation. Now a team of researchers has found that being exposed to this visual illusion can allow people to read finer print (Psychol. Sci. 2017, DOI: 10.1177/0956797617705391).

Martin Lages and Stephanie C. Boyle of the University of Glasgow and Rob Jenkins of the University of York asked volunteers with normal vision to watch a spinning spiral and then tested their ability to read letters on a standard optometrist’s chart. The researchers found that watching a spiral that appeared to contract improved volunteers’ abilities to recognize letters. Watching a spiral that appeared to expand worsened their performance.

These volunteers experienced what’s known as the spiral motion aftereffect. After a person adapts to the spiral’s motion, a subsequent static image seems to either shrink or grow in the opposite direction. The aftereffect is well-known, but until now no one had demonstrated its impact on visual acuity.

At first, Newscripts was excited by the prospect of permanently ditching our reading glasses. But Jenkins says the effect is modest and lasts for only tens of seconds before fading. The study does show that visual acuity depends not only on the optics of the eye but also on the early layers of visual processing in the brain.

Fidget spinner centrifuge

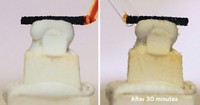

Over the past year, schoolkids have gone dizzy for fidget spinners—so much so that some school districts banned the pinwheel-shaped playthings because of the distraction they might cause. One scientist, though, has come up with a way to put that fidgeting to work. Using a low-cost three-dimensional printer, he made a handheld centrifuge based on the toy.

The mini centrifuge holds three 1.5- or 2.0-mL sample tubes at 45° angles, one in each of its lobes. Pinching the center of the centrifuge and giving it a push sends the tubes spinning between the user’s fingers. The designer, a graduate student in biophysics, doesn’t claim that the centrifuge can do separations because it’s not possible to control the speed, temperature, or duration of the spinning. But quick spins with the device can remove drops sticking to the tops of the tubes—important for scientists working with small volumes of liquid, he says.

The designer, known as Matlek, tells Newscripts that he thinks of the device as “a toy with scientific features” but that scientists might find it useful because it’s small and doesn’t need electricity. Although he printed the device’s ball bearing out of plastic, Matlek thinks that with a metal bearing the centrifuge could reach tens of thousands of revolutions per minute. Not bad for a centrifuge that fits in your pocket.

Corinna Wu wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter