Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Toothpaste compounds, including triclosan, build up in toothbrushes

Bristles and tongue cleaners accumulate and release common toothpaste components, scientists find

by Emma Hiolski

October 25, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 43

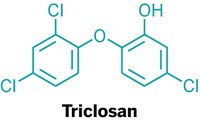

Toothpaste leaves your mouth feeling clean and tingly, but how does it leave your toothbrush? New research shows that compounds in toothpaste, including the antimicrobial agent triclosan, can build up in toothbrush heads and leach back out over time (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02839).

Triclosan was once a common component of antibacterial soaps and body washes in the U.S. Last year, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration gave companies a deadline of September 2017 by which to stop marketing those products, citing concerns about triclosan causing antibiotic resistance and a lack of evidence that triclosan-containing soaps were more effective than soap and water alone. The compound’s use in toothpaste is still approved, though, because of reports that it reduces gum inflammation, gingivitis, and plaque.

Because some nylons—materials commonly used in toothbrush bristles—can take up some compounds, including triclosan, researchers led by Baoshan Xing of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, set out to determine the fate of chemicals in toothpaste. They simulated three months of tooth brushing in the lab with 22 types of manual toothbrushes, artificial saliva, and six best-selling antibacterial toothpastes containing 0.3% triclosan (3 mg/g of toothpaste).

Triclosan and other toothpaste chemicals accumulated in elastomeric toothbrush head components such as cheek and tongue cleaners, as well as nylon bristles. More than half of the toothbrushes accumulated at least 10 mg of triclosan over the simulated three-month brushing. When the researchers switched some of those toothbrushes to non-triclosan toothpastes for two weeks’ simulated brushing, triclosan leached out of the toothbrushes.

Although triclosan uptake and release did not reach harmful levels—the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s limit for dietary exposure is 0.3 mg/kg/day—the, the authors point out that this represents previously unrecognized sources of exposure to both humans and the environment, including transport to landfills through discarded toothbrushes.

“This study really highlights how little we know about the fate of antimicrobial chemicals,” says Erica Hartmann, a civil engineer at Northwestern University who studies antimicrobial resistance. “Every time one of these chemicals winds up in a new context, that’s another opportunity for it to have unintended consequences.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter