Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Cane toad microbiome transforms its toxins

Microbe management could be a new strategy for controlling toad population growth

by Melissae Fellet

August 3, 2017

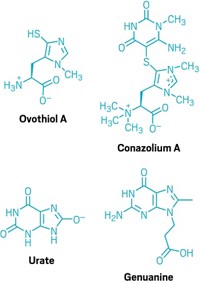

Australia’s invasive cane toads are a scourge to native species, poisoning predators with toxic secretions. But now researchers have discovered that bacteria in the glands of adult cane toads transform these toxins into hydroxylated versions found in cane toad eggs and tadpoles (J. Nat. Prod. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00134). Manipulating this microbe-mediated toxin transformation could offer a new route for controlling the exploding cane toad population in Australia, the researchers say.

In 1935, about 100 cane toads (Rhinella marina) were released in sugar cane fields in northeastern Australia to control beetles eating the sugar cane. Today, an estimated 1.5 billion toads have spread thousands of miles across the continent, killing native species, to the brink of extinction in some cases. When predators munch on a cane toad, milky secretions full of a family of steroidal toxins called bufagenins ooze from the parotoid glands on the toad’s shoulders.

Robert J. Capon of the University of Queensland previously found that Gram-negative bacteria isolated from these glands could completely degrade bufagenins (Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.064). The researchers wondered if other bacteria from the cane toad microbiome could also alter bufagenins, producing some of the types observed in cane toad eggs and tadpoles.

The researchers isolated three different strains of Gram-positive Bacillus species from the parotoid glands of two toads collected on campus. They fed the bacteria one of four different bufagenins produced by adult toads. After seven days, the researchers isolated compounds in the culture and found hydroxylated bufagenins. These derivatives are also found on cane toad eggs and tadpoles. In nature these modified toxins originate with the mother and are thought be modified in ways that protect the tadpoles and eggs in aquatic environments.

Capon speculates that a toad’s microbiome could hold clues to controlling the toad population. Inoculating the toads with other microbes that might change the bufagenin modifications as the adult females pass toxins to their eggs could be a helpful strategy, for example. “Would that reduce the viability of the eggs?” he wonders.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter