Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

Tune in to the new episode of our podcast, Stereo Chemistry, as we discuss sexual harassment in chemistry

Learn what’s changed—and what hasn’t—in the months since C&EN published its cover story on the topic

by Kerri Jansen

March 8, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 11

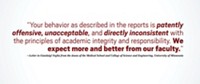

In C&EN’s second episode of Stereo Chemistry, host Kerri Jansen follows up on our September 2017 cover story on sexual harassment in chemistry to look at what has changed—and what hasn’t—since that piece was published. Jansen speaks with the reporters who worked on that story and with chemists who have survived sexual harassment, including Stanford University’s Maria Dulay and Miranda Paley of ACS. Paley posed the question shown while recounting harassment she experienced as a graduate student.

Read C&EN’s cover story “Confronting Sexual Harassment in Chemistry” at cenm.ag/harassment.

Information on the Science of Sexual Harassment symposium and harassment response workshop can be found at bit.ly/ACSNOLAworkshop.

Subscribe to Stereo Chemistry now on iTunes, Google Play, or TuneIn.

The following is a transcript of this podcast.

Maria Dulay: You know, I’d politely say no, and I kept saying no, but I sensed after the fifth no that he was getting annoyed or angry that I kept answering in the negative. Eventually I realized that the word no had no power.

Kerri Jansen (voice over):That’s Maria Dulay, a chemist at Stanford University who experienced sexual harassment while working as a research scientist there. Maria was among the women featured in last September’s cover story “Confronting Sexual Harassment in Chemistry.”

In this episode of Stereo Chemistry, we wanted to learn what’s changed—and what hasn’t—in the months since the cover story, especially in view of the #MeToo movement that exploded last fall when sexual harassment survivors across several industries—including chemistry—brought their stories to light by sharing them on social media with the hashtag #MeToo.

So today, you’ll hear more from survivors and the C&EN reporters who spent more than a year examining the role sexual harassment plays in the lives of chemists around the country. I’m Kerri Jansen.

C&EN’s September cover story on sexual harassment in chemistry, written by Linda Wang and Andrea Widener, is threaded with the stories of sexual harassment survivors. It’s on our website, you can read it if you haven’t already. We have a link in this episode’s description. But that story that got published is not the story that the team at C&EN originally hoped to write. I asked C&EN’s Jyllian Kemsley, who edited the piece, to tell us about the early days of that project.

Jyllian Kemsley: Initially we thought let’s put some data together. We know our readers, we know they’re scientists, we know they like data. So we started trying to file public records requests. We went to some of the top chemistry schools in the country and put in what we thought would be a fairly simple request just for numbers. Just the straight numbers for sexual harassment complaints in the past 10 years. And it was surprising that we couldn’t get very many numbers back. There were some schools that were super helpful and sent us exactly what we were looking for. There were some schools that said we’re not going to grant this request because we don’t have this record. Most laws are written so that they only have to provide existing records, they don’t have to create records, to which I wonder why do you not have a record of the number of sexual harassment complaints that you’ve received?

Kerri Jansen: Another thing that made getting records difficult, Jyllian says, is that schools often interpret laws in different ways, leading to an incomplete and varied dataset.

Jyllian Kemsley:Schools that want to adhere to the spirit of their state’s public records law will do things like give you the records but redact personal identifying information: names, addresses, stuff like that. But other places will say no, we can’t do this, because it’s a confidential personnel record or student record, we can’t disclose it. There’s one state in particular where written into their public records law is an exemption for any documents relating to a sexual harassment investigation of a state employee. So, I don’t know why that’s in there, but we quickly realized that we could not put together anything close to a usable data set.

Kerri Jansen: That state, by the way, is New Jersey, and that exemption applies to the state’s five public research universities.

So Linda and Andrea took the story in a different direction. They found a way to tell this story without hard numbers, ultimately speaking with more than 60 sources to piece together a picture of sexual harassment in chemistry.

Just for reference, the C&EN team started reporting this story in early 2016, a few months after BuzzFeed News broke the story about sexual harassment complaints against well-known UC Berkeley astronomer Geoff Marcy, and shortly after the New York Times covered the resignation of University of Chicago molecular biologist Jason Lieb while he was being investigated for sexual misconduct.

I asked them why they decided to dedicate so much time to this subject. The first voice you’ll hear is Andrea’s.

Andrea Widener:I think we were drawn in by the major cases we had seen in other disciplines in science and we wanted to make sure people understood that chemistry was not immune from sexual harassment just because there hadn’t been a major blow-up.

People were very reluctant to share any information even about proven cases of sexual harassment. We couldn’t really get anything that was useful.

Linda Wang:I think that’s why we decided to tell the story through the voices of the women.

Some of the women, the stories happened 40 years ago. And for others it happened within five or 10 years ago, but it was the same story of their research adviser or faculty member abusing the power that they had to take advantage of their graduate student or postdoc.

Andrea Widener: They each had their own little nuance about the horrible things that were said or done or they were made to feel bad about themselves in different ways, but I think it was pretty predictable once you’ve heard a few of them, and sadly so.

A lot of people that we would just randomly call to talk about policies or something would share their stories of being harassed. Not everyone we called, but a lot of people just had a story or could tell us about their friend or their roommate.

I think a lot of people have been in denial. They didn’t believe it was happening in chemistry. But I think it’s pretty clear from our reporting, sexual harassment happens everywhere, and it happens in chemistry.

Kerri Jansen: The impact of sexual harassment on a person’s life can be extensive, Linda says, causing not just psychological harm but also shortening people’s careers in chemistry and beyond.

Linda Wang:You really don’t know what it’s like to be a victim of sexual harassment unless you’ve been there. Some of the women that we talked to, they left chemistry because of the harassment that they experienced. I think there’s so much talent that’s lost in this, so many bright minds that feel like chemistry is a hostile environment for them.

Andrea Widener: Very few of the women that we talked to reported the situation, and when we did further reporting we found out that was very common.

Linda Wang: A lot of the women we talked to, they were afraid that nobody was going to believe them. Most of the women, they just kept quiet and they suffered through it.

Kerri Jansen: Stanford’s Maria Dulay first spoke with us for this podcast last November, two months after the C&EN cover story was published. Her story echoes that of many of the sexual harassment survivors that Andrea and Linda spoke to while reporting the story. Maria began to feel uncomfortable when a male staff member in her department repeatedly invited her to his home under the premise of a group meeting, only to later reveal she would be the only guest.

Maria Dulay: He would come up from behind and like rub my shoulders or look me up and down and say “I really like what you’re wearing” or “You look really good in that skirt.” And he would do this in front of people, and so I was embarrassed to say anything because it was public, so I just would smile and nod my head. So I didn’t do anything to stop it at the time.

Kerri Jansen: Maria’s harasser was the department manager, a primarily administrative role. Maria was a research scientist at the time, working in a lab across the street from his offices.

Maria Dulay:I decided that if I just stayed across the street and never went into that building while he was working, then I would be perfectly fine, because I would be physically away from him. The problem came when I would have to go into that building for meetings or go into the main office to even get a ream of paper for the printer. I wouldn’t go; I would ask somebody to go do it for me. I didn’t feel safe enough to go there, which is very demoralizing because, you know, I’m going to imprison myself across the street so that I would avoid him.

During all of this time I never told anybody; I didn’t even tell the professor that I was working for. Because I thought I can keep everything normal for everybody else and I’m the one who’s going to stay away, and everything will be fine. And that’s the way I thought about it for a long time, until this issue with something so simple as trying to go get a ream of paper and hoping not to run into him.

Kerri Jansen: But Maria’s plan to avoid rocking the boat by just steering clear of her harasser didn’t work.

It actually got worse after I stayed away. At the time I had to renew my contract, and he didn’t sign it for three months, and I didn’t get paid for three months. And the professor I worked for at the time, he even wondered why it was taking so long, and really these things take a couple of days, right, to get them signed and through the system. But even then, I didn’t say a word to my boss about the potential reason for the delay in signing my contract.

Kerri Jansen:The professor that Maria worked for was also the chair of the department. Years after these events, Maria says she knows he would have helped her. But at the time, Maria didn’t feel comfortable telling him what was happening.

Maria Dulay: I tricked myself into believing that the reason I didn’t tell him was because I didn’t want to upset his position as chair of the department. He interacted with the department manager, and I didn’t want to upset that relationship or perturb that balance. If it were to happen again—and I hope it doesn’t—I would make different choices. I think I would tell him. Because I thought the solution at the time was simple: just stay away, and everything else would be fine. But who knew that he was going to retaliate for so long after I said no.

For me, the main reason that I didn’t report it was not necessarily retaliation or I would lose my job or I would be demoted. It’s so much more personal than that. You know, there’s a lot of shame, I think, that comes with being involved in a situation like this. For me I thought, “I’m a reasonably intelligent person, and I’m reasonable,” and I thought that I would have been able to stop the advances of this person just by talking to him, and everybody would go on with their lives and everybody’d be happy. But it didn’t happen that way.

And that’s why I didn’t say anything because I thought people will say, “Why couldn’t you just say no and explain it to him and be done with it?” And I didn’t want to admit that I couldn’t fix the problem.

Advertisement

Kerri Jansen: Maria says she worried others in her department wouldn’t understand. Many of them were friends of her harasser and might judge her for speaking out.

Maria Dulay:I didn’t want that stigma, right? I didn’t want people looking at me a different way or whispering about me when I walked by. It was already bad enough to have the anger of this person; I didn’t want to add to that by having other people dislike me or blame me for something. So that’s why I didn’t say anything.

There’s a part of me also that didn’t want to get him fired, punished. You know, there was small part of me that thought, well, how do I prove it, who’s going to believe me? He didn’t hide it, so I thought, well, people are going to say, “She didn’t mind.” And so those are the reasons why I didn’t say anything. It’s all of that.

I wish that I had the courage back then to have reported him.

Kerri Jansen: Ultimately, Maria’s harasser resigned after being investigated for several claims of sexual harassment. Maria didn’t initiate that original complaint, but she participated in the investigation.

Maria Dulay: It felt good when it was announced that he had resigned, I thought great, we all did what we should have done a long time ago. Maybe he wouldn’t have committed all these offenses with so many other people if we had just done this sooner, or if I had just done it sooner. And that’s how I feel to this day, that I should have just said something.

Kerri Jansen: I asked Maria what she would like to see happen when it comes to how society thinks about sexual harassment.

I think we need to move away from this idea of secrecy or being anonymous, that we need to give women and men a better, clearer voice without the shame in speaking out. I think there should be much more support—in this case, right, mostly from men. That we need to be believed. I think there’s too much indifference when it comes to this topic. I just think that we should all stop thinking that this is something that doesn’t happen, or that we will address it when it does. I think we should just all be more aware of this so that we can all better control our behavior and be supportive of each other.

Kerri Jansen: When we come back from a quick announcement, we’ll talk about what’s happened since the C&EN article came out, including the #MeToo movement, how chemistry departments responded to Linda and Andrea’s story, and how Maria made an important decision regarding her own experience.

Dorea Reeser: If you’ll be attending the ACS national meeting in New Orleans, please consider attending two events C&EN has organized with the American Chemical Society Women Chemists Committee to continue the discussion of sexual harassment in chemistry.

On Monday, March 19th, sexual harassment survivors as well as people working to combat sexual harassment will come together for a full-day symposium on the science of sexual harassment. C&EN’s Linda Wang, whom you heard from earlier in this episode, will be one of the moderators of the event. Here’s what she had to say about what we can expect from the symposium:

Linda Wang: We’re going to have two great sessions. A morning session that is going to be focusing on the psychology and sociology of sexual harassment. And one of our speakers, Vicki Magley—she’s a psychologist from the University of Connecticut—she will be talking about how understanding why sexual harassment occurs can help organizations prevent it from happening. And in the afternoon, we’re going to be focusing on how universities and institutions are working to prevent sexual harassment in their departments and at scientific meetings. For example, we’re going to be hearing from Billy Williams of the American Geophysical Union about the steps that their society has been taking to prevent sexual harassment at their annual meetings.

Dorea Reeser: That symposium is on Monday, March 19th, starting at 9 AM at the Hilton New Orleans Riverside. It’s free to attend with your meeting registration. We’ll also be working to make video of that session available online shortly after the meeting for those of you who are unable to attend.

On Tuesday, March 20th, there will be a workshop on how to recognize and respond to harassment. That’ll be held from 8 to 10 AM, also at the Hilton. Tickets are required for that workshop. For details on how to purchase a ticket, follow the link in this episode’s description. Tickets cost $10.

And keep an eye on C&EN for its continuing coverage of this important issue.

Kerri Jansen (voice over): In October, the hashtag #MeToo exploded on social media as survivors of sexual harassment began sharing their stories widely in the wake of sexual misconduct revelations about U.S. movie producer Harvey Weinstein. The movement illustrates the power of these survivor’s voices, and highlighted the need to remove the barriers that often keep these stories hidden. Although the most recognizable voices came from Hollywood, one fact was made clear: Sexual harassment can happen anywhere. Even in chemistry.

Miranda Paley was among those sharing her personal experiences of sexual harassment on social media last fall. Miranda is a senior managing editor with the American Chemical Society—which publishes C&EN and thus this podcast—and she experienced sexual harassment as a doctoral chemistry student at UC Irvine. She explained her personal decision to share her story on Twitter back in October, just a day or two before #MeToo started trending.

Miranda Paley:That was sort of the backdrop, that a lot of these stories were happening. I found myself sort of explaining what it is to be a woman in science and some of the biases and harassment you face. And I went, “Oh, I’m doing this again. ‘Cause I feel like I have this conversation over and over, multiple times a year, to very sympathetic men, and they are always so darn shocked. This is from me, Miranda, not anyone else: Thank you; I do appreciate your empathy. But can we stop being shocked? It’s been a year or more of nearly constant disclosures. And that led me to posting my story.

Everyone was very supportive, and there is definitely a pretty widespread desire to change it, but maybe not a full understanding of what “it” is and what needs to change.

Kerri Jansen: I asked Miranda if, based on her experiences, she had any advice for those who want to know what they can do to work toward change.

Miranda Paley: Listen. Ask questions. Ask if there’s been a scenario when they have been made to feel “less than.” Ask what that is; find out. Because so many of these things are so micro compared to the really egregious ones, but that’s where it starts. And we’re so often told to “be cool,” not to say a joke isn’t funny. And I think men are in a unique position that they do get to make a big difference when they say a joke isn’t funny or a story isn’t appropriate. And that’s, in my mind, where a lot of it starts. You can shut it down. And you should.

Kerri Jansen: Of course, change takes time and there are still flagrant harassment cases like the ones Miranda shared in her story on Twitter; a story composed of 30 tweets that ends with “This is where I should have some inspiring, bring-it-all-together conclusion. But I don’t. Because there are not easy answers.”

The #MeToo movement gave many survivors of sexual harassment—including chemists—a chance to be heard and to support each other in their experiences. But the institutions and professional organizations where these incidents occur also have an important role in supporting survivors and helping prevent sexual harassment in the first place. C&EN reporters Linda and Andrea shared some of what they learned about how universities are trying to address this issue.

Andrea Widener: I think it’s still a hard problem for universities. Online training doesn’t stick; people don’t remember. And the kind of training that does seem to work is very intensive. You sit in a room, you discuss scenarios, you really understand what is considered harassment and what is not considered harassment, and how to report and who to report to. I think a lot of places are not either willing or able to do that kind of training.

Linda Wang: Some universities have tried mandatory reporting, which means that any staff or faculty member that sees or hears about sexual harassment are required to report it. But one of the things that people have found about that is that is takes the control away from the people who are experiencing sexual harassment.

Andrea Widener: It basically prevents people from having anyone to talk to in a position of power. They can’t even find out about their options because they can’t talk to anyone without it automatically getting reported to the university.

Advertisement

Linda Wang: What I think has happened is that there’s a greater dialogue, there’s greater conversation about this issue. A lot more people are talking about it, men, women, everybody is talking about this issue, so I think it’s something that people can’t ignore. And that it is, in its own way, making changes, but change is slow.

Andrea Widener: Even if it’s more in the community and more talked about, universities have inherent challenges. There’s a lot of motivators that push against revealing sexual harassment. We hope that more students will start reporting it, but we haven’t heard in the months since our story of a big up-swell of change happening.

Kerri Jansen: Maria Dulay still works at Stanford as a research scientist. That hasn’t changed. But what has changed is that people now know she survived harassment on that campus.

C&EN referred to Maria as Nancy in its cover story on sexual harassment to protect her identity. She later decided to go public with her name and her story.

Maria Dulay:So the C&E News article that came out in September, I didn’t reveal my identity, right, and so I was really dumbfounded by the lack of chatter in the department with regards to that article. I thought at least that, you know, I would hear people talk about or be surprised that it’s as prevalent as it is. And I spoke with my boss and I asked him if he had heard any chatter among the faculty, because there should have been, and he said no. And I thought OK, that’s very strange, and we had several more conversations about that. And I finally told him, I said, “You know, if it would make any difference to the department, you have my permission to reveal my identity. And you tell everybody—anybody, whomever you need to tell—that “Nancy” in that article is me.

I can tell you that I’m so proud of what my department has done since they found out about me to make changes locally—within the department—and then having gone out to get support or advice from the university. It made it OK, I guess, to be exposed like that.

Kerri Jansen: Maria says that policy changes are just the first step universities should take in working to combat sexual harassment.

Maria Dulay:You can make these policy changes, and they can be good policy changes, you can say, “Great, I’m glad that the university or anywhere has put this in place.” But unless the person feels safe, that they’re not going to get retaliated upon, that people believe them—that the right people believe them, if we’re talking about a university, people who can make things better for them. Unless that happens, I don’t think it matters what policy you put in place, because if people don’t come forward, what good is a policy? The people that the policy are supposed to protect are still hiding, right? And for me not saying anything, I realized was still hiding behind a secret, and if I didn’t say anything I’d be hiding behind that secret for the rest of my life. I am pretty sure that that would have happened. If there isn’t one person that believes you and supports you, or even wants to listen to you, there’s not going to be change, there’s not going to be big change. And safety is a big thing when it comes to deciding whether you’re going to say something or not. Being believed is a big part of feeling safe.

Kerri Jansen: Linda and Andrea continue to follow this subject for C&EN.

Next week on Stereo Chemistry C&EN reporter Tien Nguyen takes a close look at chemistry’s new preprint server, ChemRxiv, and how the chemistry community is reacting to it. Remember to subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or TuneIn. Thanks for listening.

End transcript.

Music credit: Audio Blocks/Footage Firm

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter