Advertisement

Imagine having an illness so severe that you would give up 15 years of your life if the symptoms would vanish. That was the average amount of time nearly 2,000 people diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, said they were willing to sacrifice if they could be symptom-free, in response to a 2007 survey (

In brief

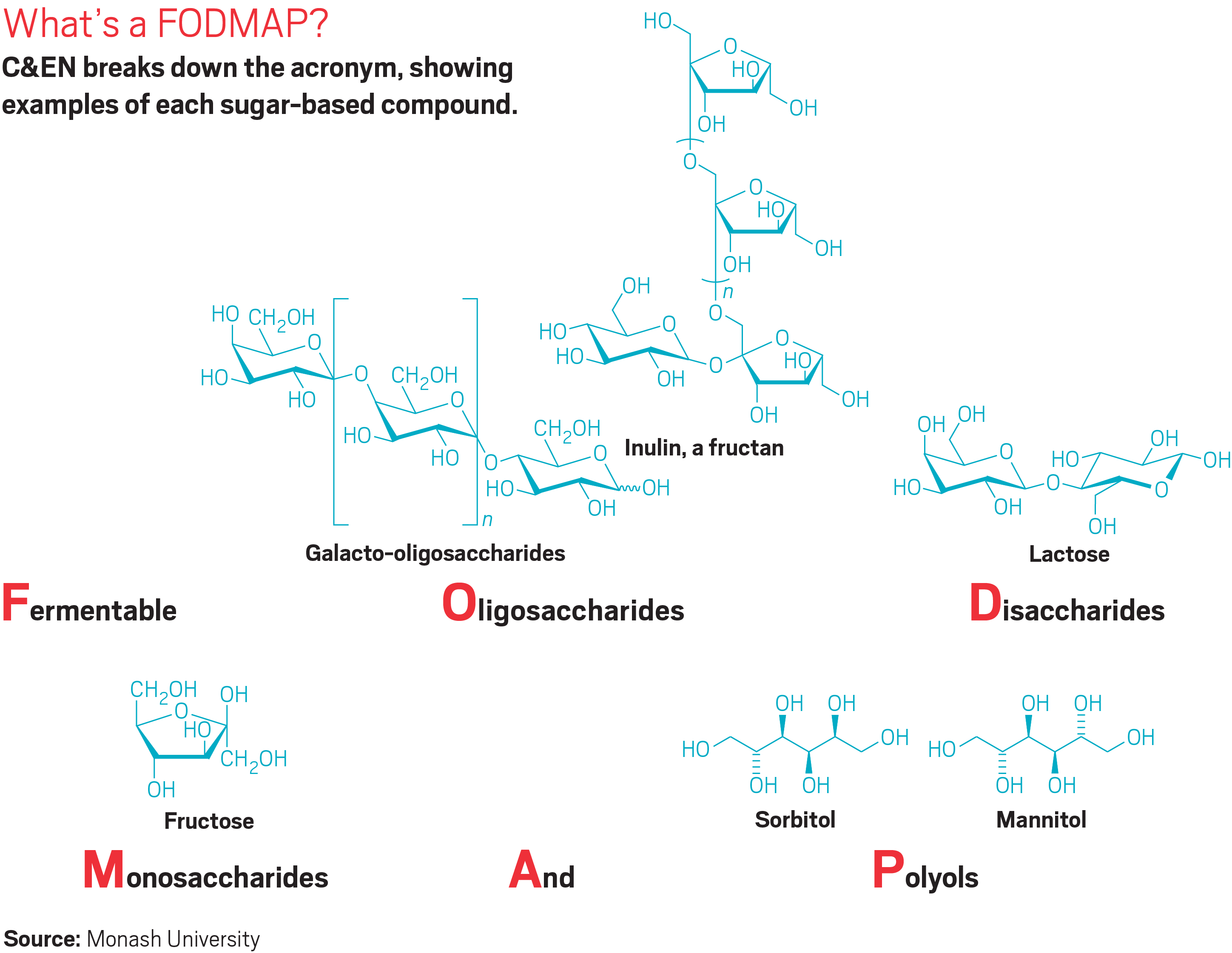

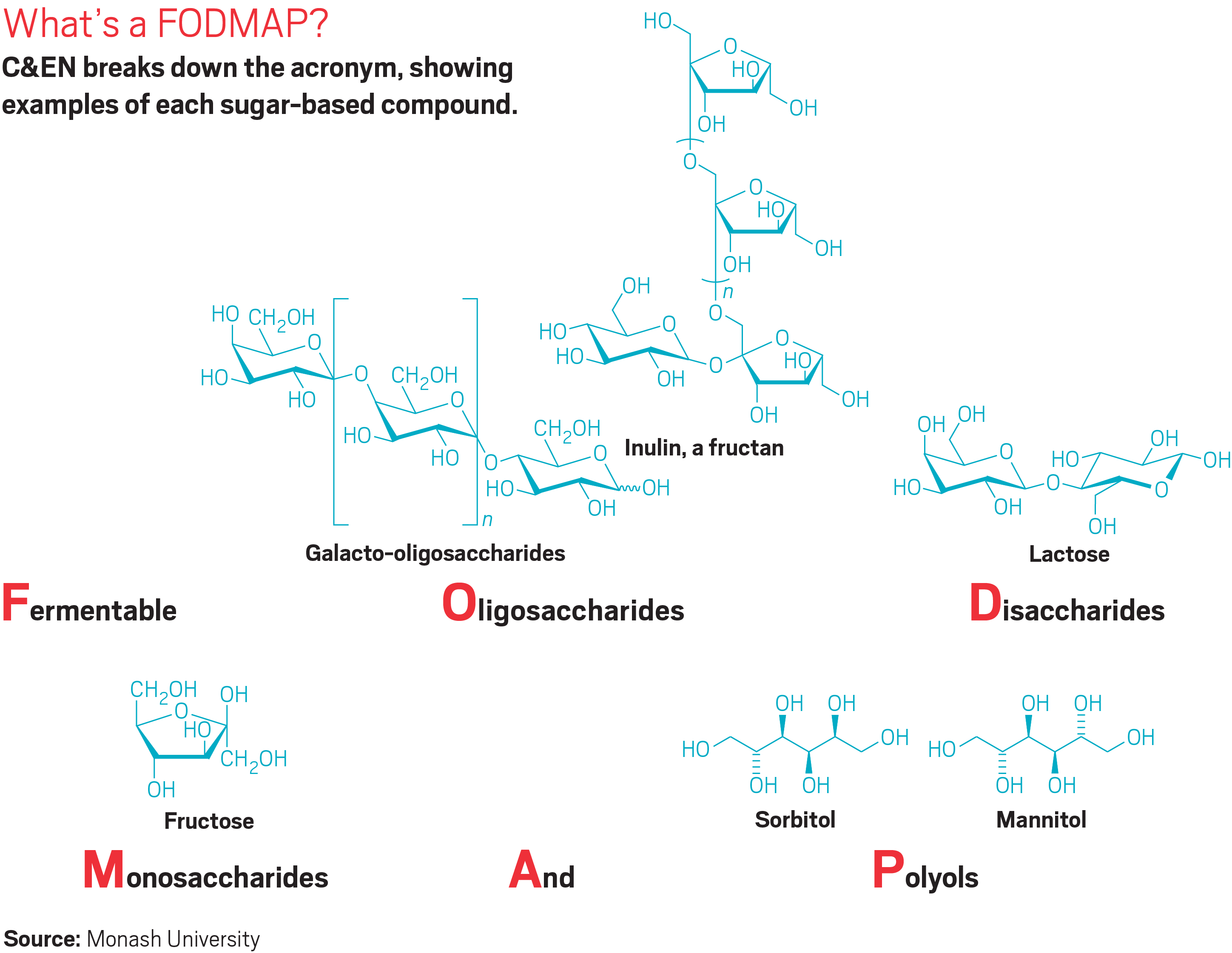

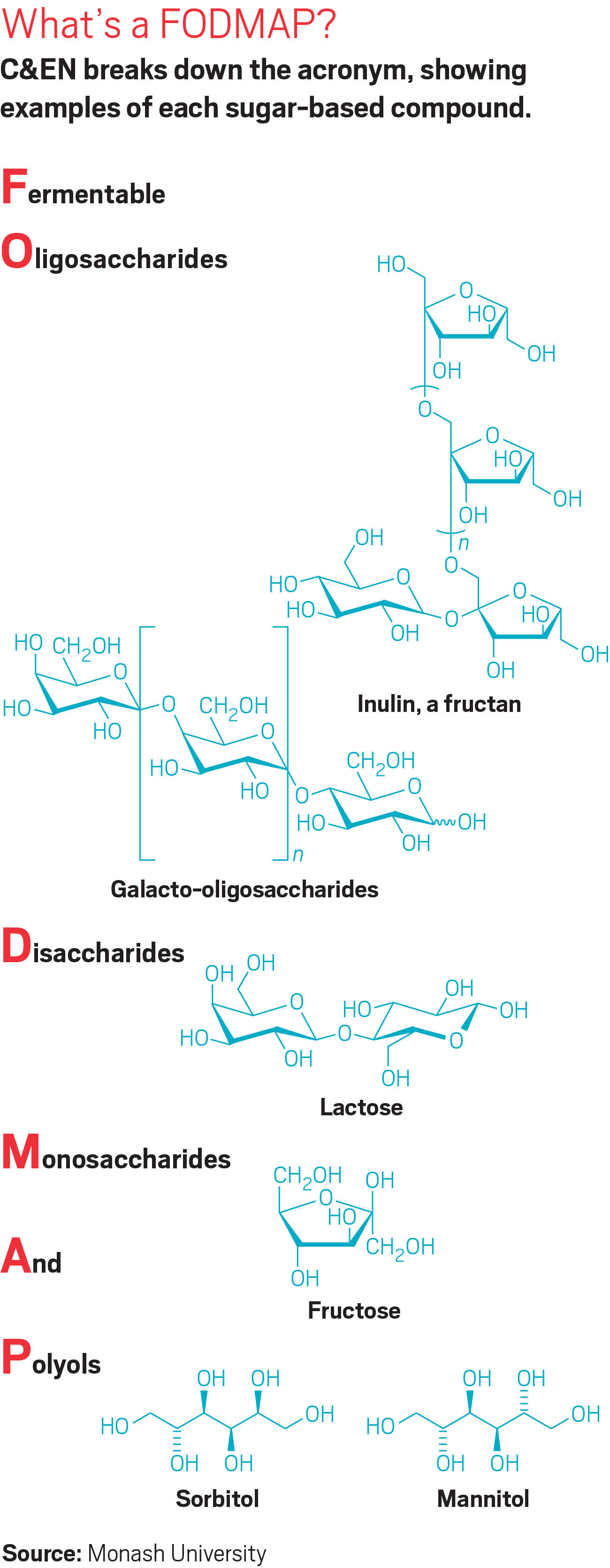

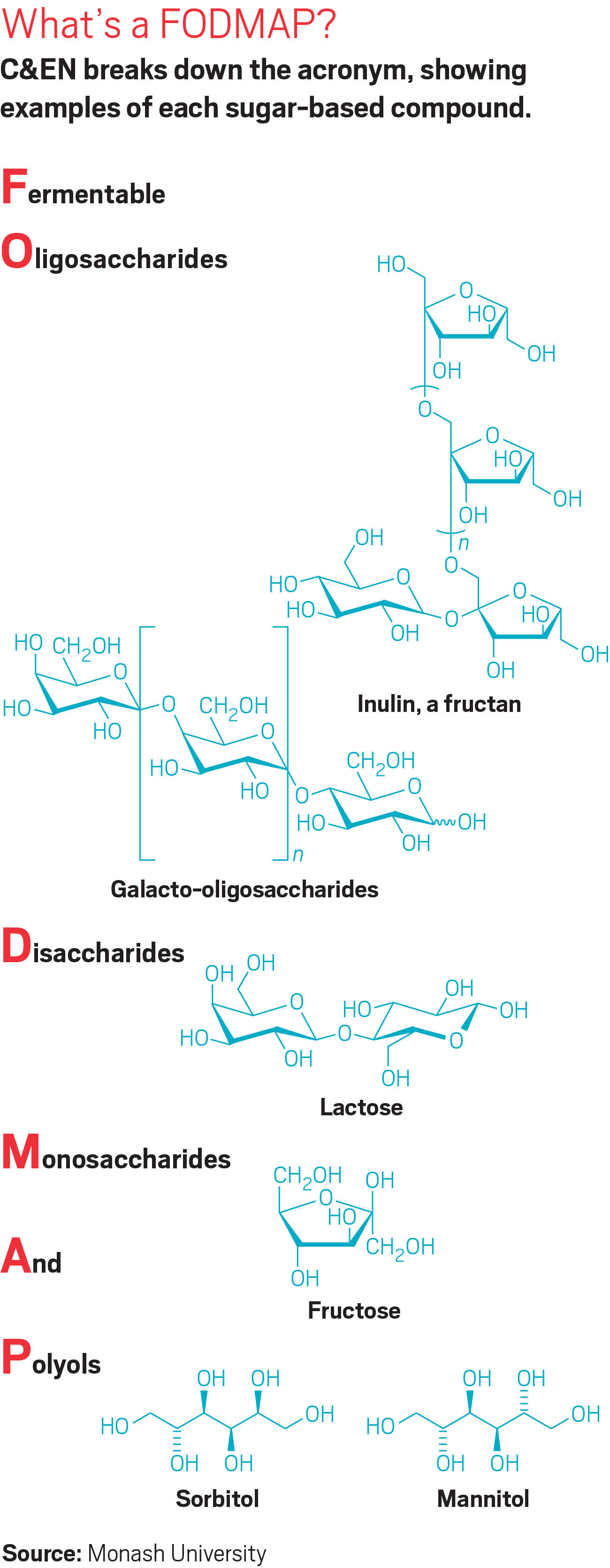

Between 10 and 15% of people in the developed world have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is characterized by unpleasant gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating and diarrhea. Over the past 12 years, doctors and scientists have systematically studied sugary substances in foods, known as FODMAPs, that they think might be triggering some forms of IBS. Read on to learn more about the low FODMAP diet, which they’ve developed to help people with IBS figure out which foods are responsible for their symptoms.

IBS—a condition characterized by bloating, abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhea, and constipation—is not the sort of thing most people talk about at the dinner table. But evidence continues to mount that what people eat could profoundly impact their IBS symptoms. Because IBS affects 10–15% of people in the developed world, relieving those symptoms could improve the quality of life for at least 100 million people.

Advertisement

“IBS isn’t a life-threatening disease. It just makes life miserable,” says Peter Gibson, a gastroenterologist at Monash University. A few years before the 2007 survey, Gibson and colleagues in Australia were beginning to suss out saccharides that may be exacerbating IBS symptoms.

They developed a regimen aimed at helping relieve IBS symptoms and began to study its effectiveness. Known as the low FODMAP diet, the plan begins with people avoiding FODMAPs, otherwise known as fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols. People on the diet then systematically reintroduce foods to figure out which of them contains the sugary molecules causing symptoms and which FODMAPs that particular IBS patient can consume without problems.

The diet pulled together a lot of information that doctors had known for years, even decades, but that they had not connected into a cohesive whole that made sense, Gibson says. For example, doctors had known since the 1960s that the disaccharide lactose in milk and in other dairy products can cause IBS symptoms. People with IBS who went on a lactose-free diet, however, rarely found relief from their symptoms because they were still consuming other FODMAPs to which they were also sensitive.

“When we put the diet together, it was much more effective than anything we had seen before,” Gibson says. “This was specifically related to definite molecules in the diet.”