Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biotechnology

Engineered cotton grows on alternative fertilizer

Crop feeds on phosphite, potentially allowing it to outwit weeds and mitigate pollution from traditional fertilizer runoff

by Carmen Drahl

June 17, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 25

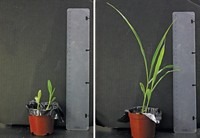

Wily weeds can develop resistance to herbicides, allowing them to compete with genetically modified crops designed to tolerate weed-killing chemicals. Now, a team is proposing another approach to genetically engineering crops to outgrow weeds: cotton that feeds on an alternative fertilizer, one that weeds can’t use (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1804862115).

“This work is exactly the sort of genetic engineering that I would like to see more of, traits that expand the realm of what farmers can do while protecting the environment,” says Anastasia Bodnar, a plant geneticist who was not involved with the work and is the policy director for Biology Fortified, a nonprofit organization that fosters discussion on biotechnology and agriculture.

Regular plants need phosphate to grow, but the new cotton can survive on phosphite instead because the crop is engineered to contain a bacterial gene that confers the ability to convert phosphite to phosphate, explains Luis Herrera-Estrella of Mexico’s National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity, who co-led the work with Texas A&M University’s.

Keerti Rathore. Their combined teams developed transgenic cotton that grows just as well on phosphite as regular cotton grows on phosphate. In soils with varied chemical and nutrient profiles, the plants outcompeted a bane of cotton farmers’ existence: Palmer amaranth, or pigweed, which resists the common herbicide glyphosate. The first trials outside the greenhouse commence later this month in Texas. A spin-off company cofounded by Herrera-Estrella, StelaGenomics, is developing the technology for use with other crops.

Phosphite is used to kill fungi in crops, but manufacturers would need to scale up production to accommodate fertilizer demands, if this strategy ever reaches widespread use. Farmers might be able to apply less phosphite than they would phosphate, Bodnar says. Phosphate can run off farmlands into waterways, where the compound promotes the growth of toxic and harmful algal blooms. But phosphite should be used carefully, Bodnar adds, because long-term use might select for bacteria in soil and waterways that convert phosphite to phosphate, thus recreating the phosphate problem.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter