Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Cancer

Mice fed a low-methionine diet respond better to cancer treatments

The special diet seems to aid treatments that target one-carbon metabolism

by Megha Satyanarayana

August 5, 2019

New research in mice suggests that a simple dietary change can improve the effectiveness of certain cancer treatments.

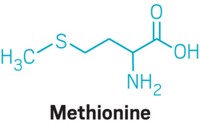

By feeding the mice a diet low in methionine, an essential amino acid that we get from meat, eggs, and some nuts, a team led by Jason Locasale of Duke University found that anticancer drugs like 5-fluorouracil could reduce tumor size in animals with cancers that were otherwise resistant to these treatments. The diet also improved radiation treatment outcomes in mice with radiation-resistant cancers (Nature 2019, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1437-3).

The study is another step toward understanding how nutrition impacts cancer outcomes, Locasale says, adding that the role of nutrition in cancer hasn’t benefited from the same rigorous molecular study as cancer genetics.

“Most of medical oncology is interested in genes,” he says, “but we now know that genes and the environment are very important. The major component of environment is nutrition.”

Locasale and colleagues thought that a methionine-reduced diet would starve active tumors, which need energy to grow and spread. These cancerous cells get a quick source of energy from a metabolic cycle called the one-carbon pathway. Several cancer treatments, including radiation and 5-fluorouracil, target this pathway.

To determine if a low-methionine diet could slow down one-carbon metabolism, the team put healthy mice on the restricted diet and used mass spectrometry to monitor metabolites in the animals. Within two days, metabolites related to methionine breakdown had dropped, indicating that the pathway had slowed. They then decided to see how the diet affected mice with cancer.

In one set of experiments, they engrafted a human colorectal cancer into mice, let the cancer grow, and then fed the mice a methionine-restricted diet. When compared with mice with the human cancer that received a normal diet, the methionine-restricted animals had smaller tumors, and analysis of their one-carbon metabolism showed lower levels of methionine-based by-products. When the team gave the mice with human colorectal cancer a dose of 5-fluorouracil that under normal circumstances would have been too low to have an effect, the tumors shrunk anyway. The treatment and the diet seemed to synergize, Locasale says.

In another set of experiments, the team gave the methionine-restricted diet to mice with a radiation-resistant soft tissue sarcoma. Tumor size didn’t change with a difference in diet alone, but the animals’ tumors became susceptible to radiation again, with tumor growth slowing markedly after treatment.

“Diet is enough, but other times it is not,” Locasale says. “Add chemo, put them together, and you get a big change.”

Lewis Cantley, a cancer biologist at Weill Cornell Medicine who trained Locasale, says that Locasale’s work is helping “establish a trend that dietary interventions with specific cancer therapies induce responses.”

Cantley has previously reported that a ketogenic diet, which is low in carbohydrates, makes certain cancer drugs work better.

The findings are interesting, but their applicability to humans remains to be seen, says Karen Vousden of the Francis Crick Institute, who had previously found that serine-depleted diets altered cancer outcomes. “This is a very exciting approach, but we will need to wait until the clinical trials have been completed before we know how well it will work in patients,” she says.

Locasale says doing methionine-restriction experiments in people with cancer is challenging, so they looked at healthy people on a low-methionine diet that was akin to a meat- and dairy-free vegan diet. What they found was that these people’s one-carbon metabolic profile matched what the researchers saw in mice, offering some hope that dietary changes might affect some tumors that rely heavily on one-carbon metabolism in humans.

“We are developing a picture that there is not a cure-all for cancer, but that diet has a big effect on cancer,” Locasale says. “But we are not at the point where you just eat that [diet] and your cancer is fine.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter