Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Chemical Communication

Volatile soil molecules entice ants to nest

The smell of actinobacteria tell ant queens the soil is safe from fungus

by Ariana Remmel

September 26, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 37

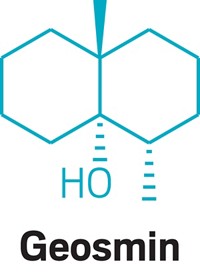

Realtors know that the smell of freshly baked cookies may entice humans to buy a house, but to red fire ants geosmin smells like home. A research team led by Daifeng Cheng, an entomologist at the South China Agricultural University, has shown that Solenopsis invicta prefer to nest in soil that gives off the fragrance of actinobacteria—namely geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol (PLoS Pathog. 2020, DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008800). That’s because actinobacteria in S. invicta nest sites help protect the ants from infectious microbes such as fungi. The researchers showed that newly mated queens are attracted to the odor of these volatile molecules, which are released from soil rich in actinobacteria—specifically Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis—and low in pathogenic fungi. As a result, the microbial perfume indicates to the queens that the soil is a safe place to start a new colony. The team went on to show that the S. invicta queens that nested in such sites were more likely to survive than queens that nested in soil without actinobacteria. This is the first study to show that chemical signals from bacteria can affect the nesting behavior of ants, Cheng says. Now his team aims to determine if these chemical signals can be leveraged to manage S. invicta infestations in public parks and crop fields.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter