Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Gene Editing

Chemistry In Pictures

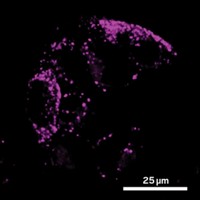

Chemistry in Pictures: Glow monkey

by Craig Bettenhausen

July 22, 2022

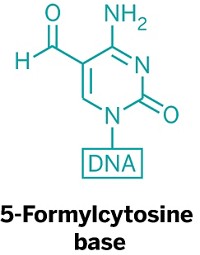

Okay look, mammals that have been genetically engineered to express fluorescent proteins have been around for a while. In fact, this writer’s first-ever article for C&EN in 2011 featured fluorescent kittens. It’s still cool. Scientists generally make glowing animals because it’s easy to tell if gene transfer was successful—just scan over the embryos with an ultraviolet light and look for the ones that glow. Sometimes, the scientists are inserting a gene of interest and are using the fluorescence as a tag, as was the case with the cats. Other times, as is the true for this fluorescent rhesus monkey, the researchers are advancing the gene-editing toolkit. Specifically, Yu Kang and coworkers at China’s Kunming University of Science and Technology were using a technique called “off-target analysis by somatic cell nuclear transfer” to evaluate the accuracy of gene-editing tools called adenine base editors. Though it has a science-fiction flair, the goal is noble: adenine base editors are being explored as a way to correct mutations that lead to gene-linked diseases, so it’s important to characterize their strengths and limitations.

Credit: Yuyu Niu; Sci. Adv. 2022, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abo3123

Do science. Take pictures. Win money. Enter our photo contest here.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter