Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Infectious disease

Calculations suggest flea and tick medications for pets could benefit people by controlling mosquitoes

These drugs could have beneficial population-wide effects in areas at risk for malaria and Zika, according to modeling study

by Cici Zhang

July 8, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 28

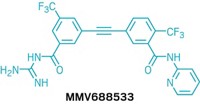

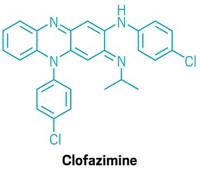

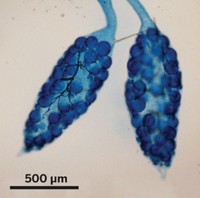

Killing mosquitoes helps control infectious diseases. A new study finds that two compounds used to protect dogs from fleas and ticks could be repurposed as human oral drugs to kill disease-spreading mosquitoes when they bite treated people. Led by TropIQ Health Sciences’ Koen Dechering and California Institute for Biomedical Research’s Peter Schultz and Matthew Tremblay, the team conducted modeling studies and found that in areas at risk, giving people these drugs would substantially reduce incidences of malaria and Zika (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA2018, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1801338115). The two compounds, known as isoxazolines, kill mosquitoes by attacking an insect-specific ion channel. Because dog and human cells clear these isoxazolines in a similar way, the team predicted that the drugs would remain in human bloodstreams as long as they did in dogs’ blood. Based on this information and other factors, such as the number of mosquitoes present in a region, modeling studies suggest that giving a single dose of the compounds to 30% of an at-risk population could reduce the clinical cases of malaria and Zika fever by 70% and 97%, respectively. The team plans to conduct human trials in one to two years.

CLARIFICATION: On July 10, 2018, the headline and deck of this story were updated to better reflect the preliminary nature of the study

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter