Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Microbiome

Gut microbes protect mice from flu

Antibiotics wipe out protection, but fecal transplants restore it

by Megha Satyanarayana

July 5, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 27

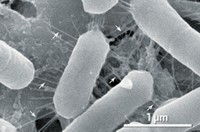

Something secreted by bacteria in the intestines of mice helps them resist influenza virus infection in their lungs, according to a new study. This protection is reversed when the mice are given broad-spectrum antibiotics. Andreas Wack of the Francis Crick Institute, who led the research, says his team is trying to figure out what this bacterial signal is. What they know is that it doesn’t affect immune cells, but rather the epithelial cells lining the lungs (Cell Rep. 2019, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.105). The signal seems to help maintain a low but responsive level of a viral defense mechanism built into these epithelial cells, which would likely encounter flu viruses first. The defense mechanism is led by interferon proteins that bind to receptors on the surface of epithelial cells, leading to a boost in production and release of antiviral proteins. Mice given antibiotics, which knock down levels of gut microbes, were more susceptible to flu infection than animals not treated with antibiotics. But the ability to resist the flu returned when the researchers performed a fecal transplant in the antibiotic-treated mice from donors that had not received antibiotics. Wack says that flu resistance is just one example—any virus that infects the lungs would be subject to this gut-lung interplay.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter