Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Natural Products

Scorpion venom yields novel alkaloid

Most scorpion venom compounds are peptides, so alkaloid comes as a surprise

by Emma Hiolski, special to C&EN

August 13, 2018

Scorpion venom packs more than a painful sting. It’s also chock full of novel bioactive compounds—most of them polypeptides—that intrigue scientists. For the first time, researchers have identified an alkaloid from a scorpion’s chemical cocktail (J. Nat. Prod. 2018, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00527).

Scorpions deliver venom through menacing stingers at the ends of their tails. Found on every continent except Antarctica, the creatures are prolific synthetic chemists: “It is estimated that scorpions synthesize approximately 100,000 venom polypeptides, but fewer than 1,000 have been isolated and characterized for their biological properties,” says Isaac N. Pessah, a molecular biologist and toxicologist at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the current study.

Though the venom of some species can deliver pain—and occasionally death—to humans, scorpion venom components have also shown promise as new ways to fight cancer or treat rheumatoid arthritis. The current study, led by Richard N. Zare of Stanford University, added the new alkaloid to the list of purified venom components.

Zare’s collaborators in Mexico, led by Lourival Domingos Possani Postay of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, collected Megacormus gertschi scorpions—a 4-cm-long species, native to the country, with venom that is nontoxic to humans—and brought them back to the lab. The team extracted venom from the bulbous gland at the end of the scorpions’ tails, then separated the components using high-performance liquid chromatography. They used mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to determine the chemical formula and structure of the most prevalent chemical species in the venom.

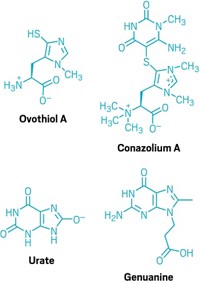

Their comprehensive analysis revealed an alkaloid with the chemical formula C16H19N3O4. The team then showed they could synthesize the compound, (Z)-N-(2(1H-imidazol-4-yl)ethyl)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methoxyacrylamide, at 73% yield from histamine and vanillin precursors.

This compound is unique within scorpion venoms, the authors note, because most of the other venom components that have been identified are peptides or proteins. The alkaloid’s function in M. gertschi venom, however, remains elusive.

Scorpions use their venom to subdue and paralyze their prey, including other arthropods, insects, and occasionally small lizards or mice. But when the team tested the alkaloid on crickets in the lab, it had no discernible effect on the insects.

Alkaloids typically serve as defensive compounds in both plants and animals (for example, in the skin of poison frogs) rather than venom components, says Kenneth J. Shea, a chemist at the University of California, Irvine. “Venom is typically a cocktail of peptides and proteins that often act synergistically, so it might be difficult to attribute a specific role to this compound,” he says.

The new alkaloid is chemically similar to feruloylhistamine, a natural product extracted from plants that can lower blood pressure, so the authors suggest the new compound warrants further study.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter