Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Editorial: Skin-care science and skepticism

by C&EN editorial staff

April 19, 2024

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 102, Issue 12

The pitch was bold: suntan without the sun. One of the ingredient maker Givaudan’s big pushes at this year’s In-Cosmetics Global, a trade show held last week in Paris, is a plant extract that the firm says grants the benefits of being out in the sun without the drawbacks.

Specifically, Givaudan claims that Neuroglow stimulates the skin to produce melanin, the pigment behind human pigmentation and tanning. The firm says the ingredient also promotes the release of endorphins, vitamin D, and oxytocin—molecules that promote peaceful, good feelings. All this without sitting in the sun and the risks of cancer and premature skin aging that conventional tanning brings.

Such claims are exciting but a little hard to believe.

Personal care ingredients are split into two groups, three if you count fragrance separately. Functional ingredients include the surfactants, moisturizers, solvents, and other compounds that give products their physical properties and generally make up most of their mass.

Active ingredients, the other category, elicit targeted chemical or biochemical responses from the skin, hair, or other tissues they’re used on. They are the ingredients that allow companies to advertise special claims, such as those that Givaudan makes with Neuroglow.

A typical clinical trial for a personal care“active” involves 20–30 people and one round of testing per claim. Givaudan had panels of 22 and 41 for the tanning and mood-boosting claims, respectively, along with in vitro tests for the biochemical claims. In contrast, a drugmaker seeking approval from the US Food and Drug Administration has to put its molecule through animal tests and then two to three rounds of human trials involving hundreds to thousands of people. The results must demonstrate both safety and efficacy.

Drugmakers can recoup these costs with high prices, but the margins are thinner in personal care. A Givaudan representative at the show said the firm crafted its biochemical claims carefully to keep Neuroglow on the cosmetic side of the FDA. That must have been quite the tightrope to walk, given the broad US regulatory definition of drugs.

This is not to disparage the scientific work that goes into clinical trials for personal care ingredients, but we should be wary of equating the resulting assertions with those from pharmaceutical-grade trials.

Consumers might accept a different burden of proof for the efficacy of drugs that save lives than for that of cosmetics, which serve softer purposes. Maybe, given how costly it is to prove that a molecule works, it’s OK to leave it up to consumers to decide whether they see an improvement to their skin or hair.

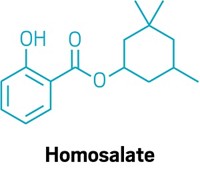

But when it comes to safety, standards should be as ironclad for cosmetic actives as they are for drugs. We still see too many examples of unsafe cosmetics, including talc, hair straighteners, and, in parts of Africa and Asia, creams that lighten skin to fulfill racist beauty standards.

On safety, the European Union arguably has a better system than the US does. The EU requires rigorous safety testing before any new personal care ingredient is allowed on the market. The US, meanwhile, has a relatively short list of banned substances; consumer product makers are largely free to roll the dice with anything else.

If a personal care product starts hurting people in the US, the FDA can ask for, but not demand, a recall. It’s mostly up to injured consumers to punish the offending company with lawsuits. The burden of proof and the risk of loss are on the public, not the corporation looking to make a profit.

This editorial is the result of collective deliberation in C&EN. For this week’s editorial, lead contributors are Craig Bettenhausen and Laurel Oldach.

The views expressed are not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter