Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Farming a flower to help fragrance last longer

North Carolina’s clary sage crop protects a perfume’s last drop

by Melody M. Bomgardner

April 21, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 16

Credit: Ashland | Farmers in North Carolina grow clary sage for the perfume industry.

COVER STORY

Farming a flower to help fragrance last longer

Northeastern North Carolina, not far from the coast, is a long way from the fine fragrance houses of Europe. But the best noses in France have farmers in this region—and its peculiar-smelling purple flower—to thank for their perfumes’ lasting charms.

The farmers cultivate clary sage for Avoca, a natural products company owned by the specialty chemical maker Ashland. Avoca has been in the clary sage business for more than 40 years. Each year it contracts with farmers to grow its special clary sage cultivar, which has been bred to produce high quantities of a waxy substance called sclareol.

Sclareol is an important raw material for perfume and other fragrance products. It is made into a replacement for ambergris, a substance so rare that it trades for about the same price as gold. A waxy secretion from the stomachs of sperm whales, ambergris on rare occasion washes up on beaches.

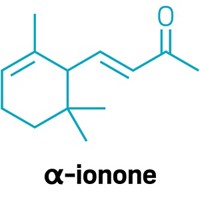

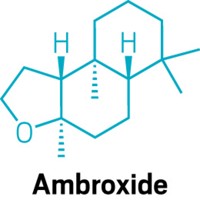

Ashland uses solvent extraction to get sclareol from clary sage. From that it produces sclareolide, which major fragrance houses then transform into an ambergris-like compound called ambroxide.

But what would perfumers want with whale vomit, anyway? Perhaps surprisingly, ambergris has a pleasant aroma—a bit musky, sweet, and earthy. Similarly, ambroxide brings a woody amber note. But the substance’s main role is as a fragrance fixative.

“There is a fixative in every fragrance formulation,” explains Guus Gerritsen, Avoca’s director of sales and marketing. “It lowers the vapor pressure of all the volatile compounds in a fragrance so they will not disappear.” In a fine fragrance, the fixative helps the last drop in the bottle smell just as good as the first.

And those fabric softeners that promise to make your towels smell like spring flowers for 2 full weeks? They get an assist from ambroxide, too.

Another benefit of ambroxide is that it boosts the performance of other scent molecules in a fragrance formulation, meaning perfumers can use them in lower quantities.

These days, perfume ingredients obtained from animals are not trendy, but ones from plants definitely are. And while some plant-based ingredients can be difficult to source reliably, that’s not the case for sclareol.

Gerritsen says the clary sage crop is sustainable for the farmers and the environment. Avoca buys the output from every contracted acre, even if that means a surplus for the year. All the clary sage is grown within a 2 h drive of the production plant. After sclareol is extracted, the spent biomass is hauled back to the farms to be spread on the fields.

Avoca has great confidence in its supply chain, but the firm isn’t resting on its laurels. It is working with Elo Life Systems, a gene-editing company, to further increase the amount of sclareol found in its clary sage plants.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter