Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Mergers & Acquisitions

Takeda to buy Maverick’s bispecific antibody technology

The biotech firm’s cancer immunotherapies might offer a safer and more effective dual-action design

by Megha Satyanarayana

March 10, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 9

Takeda Pharmaceuticals is exercising an option worth up to $525 million to buy Maverick Therapeutics, a biotech firm developing bispecific antibodies, a class of drugs that binds two targets instead of one.

The deal builds on a four-year collaboration between the companies, under which Takeda invested $125 million to develop Maverick’s technology for making bispecific antibodies.

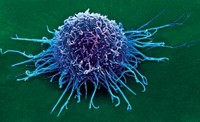

Most bispecific antibodies are designed so that one part binds to a target on a cancer cell, and the other tethers to an immune cell that can kill that cell. But creating molecules that are both safe and effective has been challenging, says Jon Weidanz, an immunologist at the University of Texas at Arlington. The molecule needs to stimulate the immune system enough to kill off cancer cells, but not send it into overdrive, causing a serious condition called cytokine release syndrome.

Safety concerns recently prompted Amgen, which has an approved bispecific antibody for leukemia called blinatumomab, to halt trials of other bispecifics. Regeneron has also stopped trials of its bispecific, odronextamab, because of cytokine release syndrome.

Maverick is trying to overcome those off-target affects by building bispecific antibodies that are inactive until they find their cancerous target. Once stuck to the cancer cell, protein-snipping enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases, which are more abundant around tumors than healthy cells, lop off a part of the drug that blocks its ability to attach to T cells, says Maverick’s head of research ad development Chad May. Now freed, the bispecific antibody forms a dimer with another of its kind, and can activate T cells to kill the tumor.

The deal gives Takeda a portfolio of early-stage bispecific antibodies, including MVC-101, which is in early clinical trials for cancers that overexpress a protein called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and MVC-280, in preclinical studies for tumors that express the immune checkpoint protein B7-H3.

Weidanz, who is exploring cancer-specific targets for bispecific antibodies as a way to overcome off-target cell killing, says that Maverick’s approach might work to get around safety issues that have recently thwarted several clinical trials.

“I do like the idea of creating a molecule that is inactive until it’s in the tumor microenvironment. I think that’s a nice step in the right direction of reducing the issues of safety and toxicity, but I’m from the camp that thinks targets are a big part of that,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter