Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Specialty Chemicals

Can superglues get better? Arkema thinks so.

The firm wants to bring new chemistry to the cyanoacrylate adhesives business, which hasn’t seen any in 60 years

by Michael McCoy

March 24, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 11

Most of us have used Krazy Glue or another brand of cyanoacrylate adhesive. We may even have an old tube in a drawer somewhere, hardened and rendered useless with time. We think of these instant superglues as good for fixing a broken mug or trophy and not much more.

Things are different in the industrial world, where cyanoacrylates are robust members of the class of glues known as engineering adhesives. They are appreciated for their ability to bond a wide range of substrates quickly and tightly. Improved over the years with viscosity modifiers, tougheners, and other additives, they are applied in areas such as electronics, auto and jewelry assembly, and footwear.

But the basic chemistry of cyanoacrylates has changed little since the technology was developed just after World War II, says Guillaume Desurmont, senior vice president of the durable goods business at Bostik, the adhesives division of Arkema.

Desurmont and his colleagues want to shake the industry up. After entering the superglue business through an acquisition, Arkema has formed a production venture that, Desurmont says, will lower costs and allow new cyanoacrylate monomers to be synthesized for new applications. Competitors are unimpressed, saying they are constantly improving the adhesives and going after new markets.

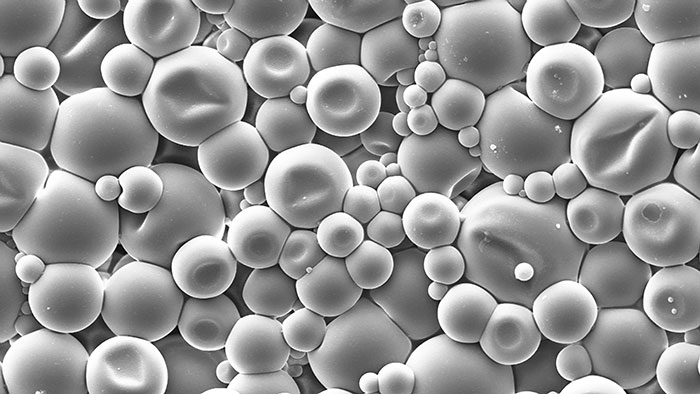

Cyanoacrylates occupy a unique niche in the adhesives world. Whereas most adhesives are viscous polymers or large molecules, cyanoacrylates are fluid small molecules that penetrate many surfaces, and their polar nitrile and ester groups react with most of them. Polymerization and bonding take place almost instantaneously upon contact with moisture or neutralizing chemicals.

The first commercial cyanoacrylate glue, based on methyl cyanoacrylate, was invented in the 1950s by the Eastman Kodak chemist Harry W. Coover Jr. It was named Eastman 910 and, later, Permabond 910 after the business was sold. Today, more than 95% of cyanoacrylate glues on the market are based on ethyl cyanoacrylate, or ECA, Desurmont says.

James E. Swope, senior vice president at the ChemQuest Group, a specialty chemical consulting firm, was involved with Permabond 910 and other cyanoacrylates for many years while an executive at Permabond. Some of his best customers were car companies, which use cyanoacrylates to adhere interior plastic trim, and speaker makers, to glue cones and dust caps.

“We used to call them convenience adhesives,” Swope says. They are easy-to-use, single-component products, but they aren’t as strong as polyurethanes or epoxies. They work great on plastics but less well on metals or in applications that require moisture or chemical resistance.

Permabond and competitors like Henkel, 3M, and Cyberbond, now part of H.B. Fuller, made improvements to cyanoacrylates, such as adding rubber to increase toughness and rheology modifiers to alter flow. “They were basically formulary changes, not backbone changes,” Swope says. “Historically, developments in cyanoacrylates have been incremental.”

Despite their limitations, cyanoacrylates are big business. Swope estimates the North American market for industrial cyanoacrylates to be worth roughly $250 million per year. Joe Silvestro, one of the founders of Cyberbond and now H.B. Fuller’s global business director for health and beauty, says cyanoacrylates and other acrylates are the second-largest engineering adhesives category, after silicones.

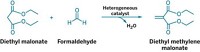

Since Coover’s day, cyanoacrylates have been synthesized via the Knoevenagel condensation, in which an alkyl cyanoacetate and formaldehyde react in the presence of a basic catalyst. The problem is that the reaction doesn’t stop there. It continues to create a prepolymer that must be broken down, or cracked, back to the monomer at high temperature. The process is costly and precludes the creation of certain temperature-sensitive monomers.

Although companies have fine-tuned the Knoevenagel condensation over the years to create ECA at decent yields, few other monomers can be made effectively. “This process is old. Very, very old,” Desurmont says. “Some people have found very interesting properties with new monomers, but no one could produce them.”

In 2013, Ramón Bacardit, a research executive at Henkel, left the company to form Afinitica, a spin-off based in Barcelona, Spain, with ambitions to update the Knoevenagel condensation.

The following year, Afinitica filed for a patent on a “crackless” method of making cyanoacrylates and other 1,1-disubstituted ethylene monomers using an ammonium or iminium salt as a catalyst. By sidestepping the high-pH conditions of the Knoevenagel condensation, the patent says, the new process stops at the monomer and eliminates the depolymerization step.

Separately, Afinitica developed a system that uses ultraviolet light and a photoinitiator to speed up cyanoacrylate curing.

Although Henkel and Afinitica cooperated for several years, Henkel ultimately decided not to pursue the crackless technology. Arkema, in contrast, saw in Afinitica an opportunity to get into the cyanoacrylate business as part of its overall goal to become a player in engineering adhesives, a category that also includes silicones, anaerobic adhesives, and epoxies. Arkema acquired Afinitica in 2018.

In January of this year, Arkema took a next step, forming a joint venture with the Taiwanese cyanoacrylate maker Cartell Chemical. The venture, in which Arkema has invested about $11 million, will build a plant at Cartell’s site in Taiwan to scale up the crackless technology. Desurmont says he expects it to open by the end of the year.

The new plant’s initial target will be 2-methoxyethyl cyanoacrylate. Known in the trade as MECA, this cyanoacrylate can be made with the Knoevenagel condensation, but yields are low, Desurmont says, and the purification process is costly. Adhesives formulators like MECA because, unlike ECA, it’s odorless. It also doesn’t cause blooming, the white glaze that appears after ECA hardens.

Also on Bostik’s wish list are products like n-butyl cyanoacrylate, which has good bonding to rubber substrates, and 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, which is used in wound-closing adhesives. But what excites Desurmont the most are the dozens of phone calls and emails Bostik has received since the scale-up plan was announced from firms seeking cyanoacrylate molecules they’ve always wanted but couldn’t find or make.

Desurmont sees opportunities for the crackless method—with or without the light-curing technology—in industries including electronics, eyewear, auto manufacturing and repair, filtration products, and toys. Potential customers will have other ideas as well, he says. “Some companies are reaching out to us for access to a particular monomer, but they don’t tell us why.”

New monomers aren’t the only way to innovate in cyanoacrylates, H.B. Fuller’s Silvestro points out. Another is purity. At a facility in Japan, H.B. Fuller makes what Silvestro calls the world’s purest butyl and octyl cyanoacrylate for eyelash extension and medical bonding applications.

And customizing monomers for particular applications is key. In eyelash extension alone, H.B. Fuller offers roughly 50 formulas, Silvestro says. Likewise, Dan Alb, the company’s senior chemist for engineering adhesives, points to the filter industry, where H.B. Fuller formulates custom hybrids of cyanoacrylates and other ingredients that bond filter material to multiple metals and gaskets for use under a range of conditions, including diverse pH.

Swope, the consultant, says he’s happy to see innovation continue in the industry he served for many years. He’s particularly keen on the prospect of new cyanoacrylate chemistry, though he’s seen too many lofty claims in his career to be a convert yet.

Desurmont is confident that Swope will be a believer soon. “We are bringing innovation into a market that hasn’t seen innovation in 60 years,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter