Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Employment

Young UK chemists question what they are worth

Chemistry graduates navigating the UK industry job market are increasingly disheartened by roles that offer them disappointing remuneration and low job security

by Vanessa Zainzinger, special to C&EN

December 1, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 47

Nessa Carson, a synthetic organic chemist, says she is “extremely lucky” to be working for a big pharmaceutical company in southeast England. Since she moved back to the UK in 2017, after completing a master’s degree at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Carson says she has seen many friends and colleagues leave chemistry because of a job market that offers young chemists fewer opportunities for exciting science or financial gain than they had hoped for.

“Generally, people are frustrated,” she says. “They don’t feel valued.”

The UK offers early-career chemists interested in industry—who normally have postdoc experience, a PhD, or a master’s degree—plenty of opportunities to work in one of the country’s many thriving contract research organizations. CROs are growing and recruiting steadily as drug companies in Europe and elsewhere increasingly look to outsource their R&D. Positions in big pharmaceutical companies, on the other hand, are rare, says Carson, who runs a Twitter account (@ukchemjobs) that accumulates and shares chemistry jobs available in the UK.

In most of the industrial positions open to young chemists, remuneration and job security are low, Carson says. “I think the market selects for people who absolutely love chemistry because that’s what they want to do with their lives. Others know they will be better off going into finance or management consulting. That’s what the people I did my undergraduate degree with are doing.”

The mood in the UK among early-career chemists who actually want to do chemistry is somber. Disappointed by the roles the job market has to offer, chemistry graduates say they are feeling undervalued and underpaid. Many are threatening to leave the country for better opportunities elsewhere.

CROs consider themselves attractive workplaces for young chemists. The companies, which offer a range of drug-discovery services—including medicinal chemistry, analytical chemistry, and lead optimization—allow researchers to participate in various projects, collaborate with people with different skill sets, and learn a lot about drug discovery, says Natalie Insley, human resources operations manager at the CRO Sygnature Discovery.

The Nottingham, England–headquartered company employs about 330 people and is experiencing constant growth, Insley says. Staff turnover is “generally low.” Sygnature also runs training programs within its chemistry department that allow students and recent graduates to gain practical work experience with the company.

Nathalie Dubois, the company’s marketing coordinator, adds that most researchers in its chemistry department are in their late 20s. “It’s a young culture, and we offer continuing development, internal and external training, problem-solving sessions, conference attendance, and the opportunity to develop their skills,” she says.

Some researchers, however, say they find little passion in working for a CRO. “It’s safe to say that where I am working, nobody at the junior level is particularly happy with their jobs,” says Katy, a medicinal chemist who, to protect her job, asked that her full name not be used.

Katy works for a large CRO in east England that hires chemists on fixed-term contracts. This means job security is low for everybody, she says. “Half the people I work with are [University of] Cambridge graduates, fantastic chemists, but that doesn’t matter. The company offers them no help with career progression.” Earlier this year, the company laid off 15 chemists, then hired another 15 a few months later, she says.

The work itself lacks passion, says Katy, who misses the innovation and target validation that would be part of a research job in a company that pursues its own projects. “You’re just told: ‘Here’s your target; go make some drugs.’ I always knew this isn’t the kind of work I’m interested in, but I didn’t have much of a choice,” she says. Katy moved back to the UK earlier this year when she was forced to end a postdoc at the University of California San Diego after a member of her family was taken ill. The only industry jobs she could find were with CROs, she recalls.

Frustration with the job market is making some young chemists consider moving to mainland Europe, where they hope they’ll find a greater variety of jobs and higher salaries. At a gross salary of £32,000 ($41,000) per year, Katy says she is paid around £10,000 less than a former postdoc colleague who left San Diego with her but took a job at a drug company in Berlin.

Cheap science

Another young chemist, Javier, moved to England from Spain for grad school at a public university in the northwest. Like Katy, he asked that, to protect his job, his full name not be used. Javier picked up plenty of job offers in the UK after completing his PhD, but he rejected them all because of the low salaries on offer.

“Perhaps my expectations were high because I did my PhD on a Marie Curie scholarship, which is roughly double the normal PhD salary in the UK,” Javier says, referring to a scholarship granted by the European Commission. “But in any case, the offers I got in the UK were about 40% lower than the ones I received in [continental] Europe.”

Javier settled for a job with a large specialty chemical company in Belgium. His salary is €49,000 ($53,900), a big step up from the best offer he received in the UK, at £28,000 ($35,900).

Even if the salary were equal, Javier says he saw no benefit to staying in the UK. Companies in the country normally offer 25 days of vacation a year, compared with the 33 days he gets in Belgium. Housing costs in the UK are 57% above the European Union average, according to the European Commission’s statistical office, Eurostat, topped only by Ireland and Switzerland. In comparison, housing costs in Belgium and Germany are 14% and 11%, respectively, above the EU average.

Tax comparisons between European countries are difficult to make, but according to research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the UK imposes relatively low taxes on the incomes of median earners, which are what most entry-level chemists would be.

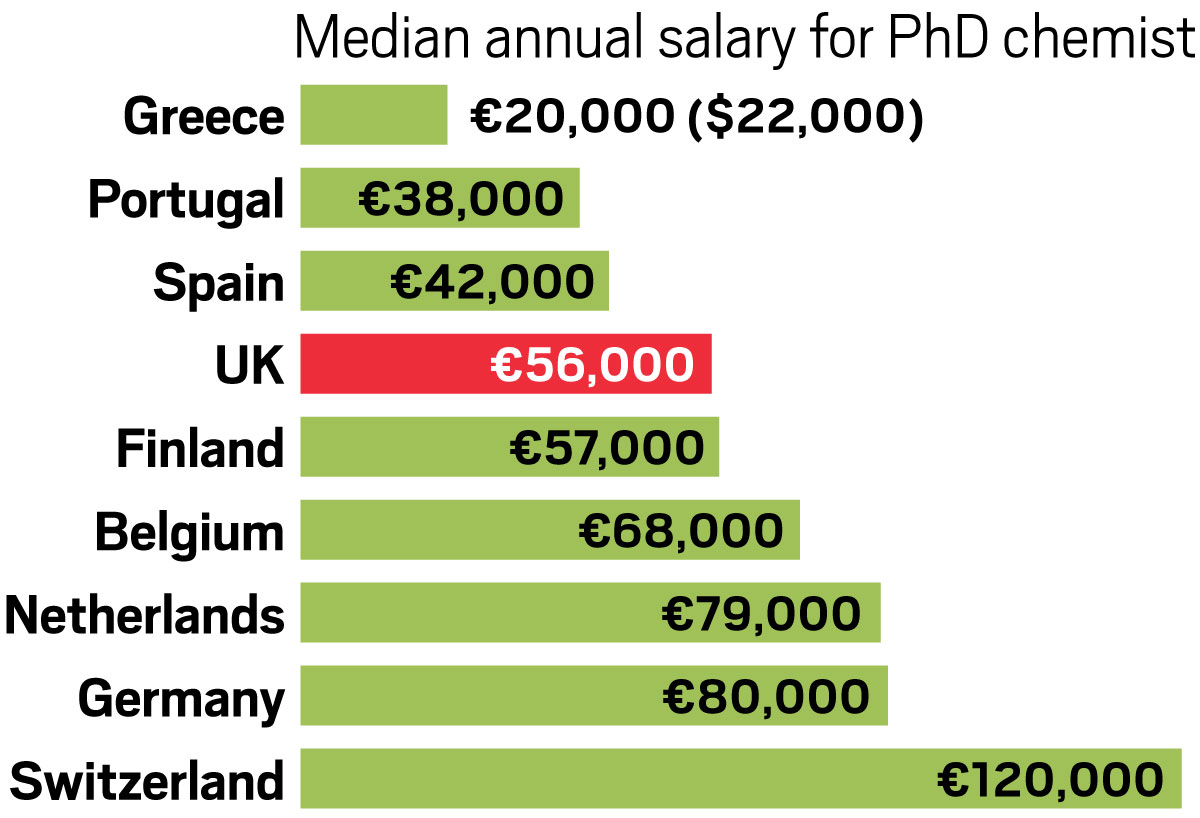

Median salaries for PhD chemists, meanwhile, are lower in the UK than in other wealthy European countries, like Finland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, according to a study published last year by two nonprofits, the European Chemistry Network Association and the European Chemical Society. There are no statistics on how this gap manifests itself in the income of entry-level chemists specifically. A Royal Society of Chemistry survey published last month found that the median salary in the UK for early-career chemists is £33,200.

Paul Mears, head of chemical recruitment at Science Solutions Recruitment in Cheshire, England, often sees early-career chemists entering the job market with unrealistic expectations. Universities don’t always prepare their students for the reality of a highly competitive market with salaries well below what is promised by industries such as financial services, which hire chemists into nonresearch roles. He advises young chemists to build relationships with recruiters before they leave school to gain a realistic picture of the market and figure out what kind of position will suit them best.

Mears’s clients are CROs, contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs), local manufacturers, and start-ups. Most of them are small, independent firms that are likely to offer young recruits job security but low salaries.

Some large companies offer great salaries under graduate schemes—programs that combine paid work and training—for a lucky few, but many more chemists are likely to be hired on a contract basis “without necessarily compensating for the lack of security,’’ Mears says. He adds that the UK chemistry job market is buoyant, despite the uncertainty surrounding Brexit, the country’s impending exit from the EU.

Still, more and more chemists are moving to continental Europe for better job opportunities and higher wages, Mears observes. This is a reverse from 10 years ago, when chemists in postrecession continental Europe were tempted to the other side of the North Sea. Mears doesn’t blame Brexit but rather the fact that the Continent now offers comparable or even better salaries and jobs.

“Ten years ago we were gaining talent; now we might be losing it. I think this is driving a skills shortage in the UK,” he says.

The Northumberland, England–based CDMO Sterling Pharma Solutions says it has not seen its young recruits shun the UK for greener pastures. “We continue to receive many applications from chemists based in mainland Europe, and our recent recruits have included several Oxbridge graduates too,” says Sterling R&D director Mike Gibson, referring to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, two prestigious British schools. “We feel that we would not be receiving those applications if there was a significant salary disparity.” He adds that the salaries the company offers go far where it is based, in northeast England.

The 400-employee-strong firm is due to start recruiting researchers for a new milling and micronization facility. Gibson says Sterling likes to hire both fresh PhD graduates and experienced chemists. He adds that the CDMO has worked hard to become an attractive place to pursue a career, with “excellent development and progression routes into different areas of the firm.”

James Ayres, a synthetic organic chemist, is skeptical of relying on progression opportunities within a UK company. When searching for an industry position after graduating with a PhD from Cardiff University in 2018, the highest job offer Ayres received was £25,000. The company offered to increase the salary to £28,000 after 3 years. He is now working as a postdoc at the University of Leeds and earning £32,000.

Academia in the UK is still a great place for chemists, Ayres says. “I’m happy in my current position—I’m learning new skills, getting paid pretty well, and the science we’re doing is excellent,” he says. The chemical and drug industries, in contrast, are not as vibrant as they used to be, Ayres says. “There are still opportunities to do interesting work, but money matters too.”

Javier calls on UK companies to do better in valuing their young talent. Working conditions—including salary, holidays, working time, and flexibility—are important, he says. “I work to have a life; I don’t live to work,” he says.

Javier says he will stay in Brussels for a while but is hoping to someday move to Switzerland, where salaries—and living costs—are significantly higher. Ayres and Katy are both considering moves to mainland Europe, depending on family circumstances and the outcome of Brexit, which is likely to make it harder for young British chemists to live and work on the Continent.

Carson, the drug company chemist, says she is happy in her current job but emphasizes that it’s her love for chemistry that keeps her going. “If I were very sensible, I would probably leave chemistry,” she says. “If I was a bit sensible, I would leave the UK, and I think I will eventually.”

Vanessa Zainzinger is a freelance writer based in England.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter