Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

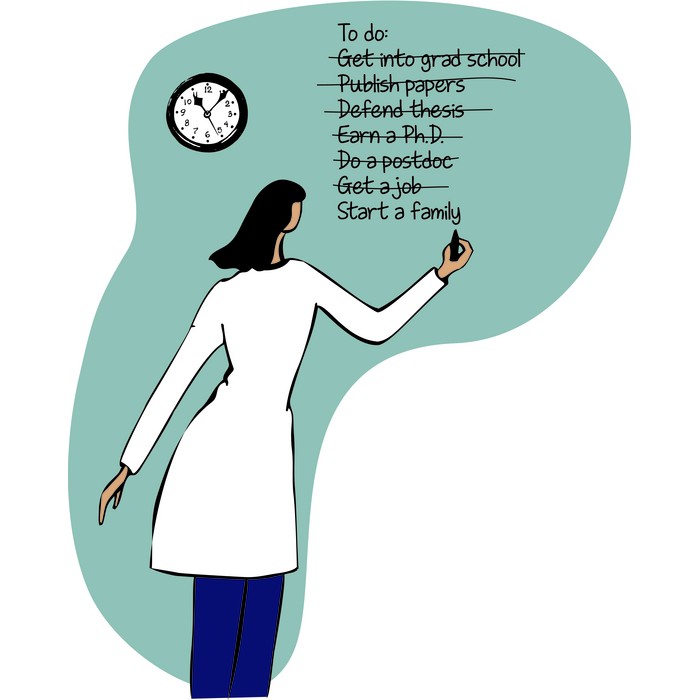

Women In Science

Movers And Shakers

Brazilian chemist Joana D’Arc Félix de Sousa on her path from poverty to PhD and inventor to teacher

Raised by a tanner and a maid, she now advocates for underprivileged youth

by Meghie Rodrigues, special to C&EN

March 10, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 10

Joana D’Arc Félix de Sousa firmly believes in science as a tool for positive social impact. Raised by a tanner and a housemaid in Franca, in the interior of Brazil, she went on to earn a PhD in chemistry from the University of Campinas.

She is listed as an inventor on several patents. Among her inventions is a way to treat pigskin to remove fat and protein to make it less likely to be rejected when used for skin grafts in humans.

In 2002, Félix de Sousa took a teaching position at Professor Carmelino Corrêa Júnior Technical School in Franca, where she has involved students in research to turn tannery waste into fertilizer and a cement for bone reconstruction, as well as to develop a dermatological shoe that releases antimicrobial enzymes to treat diabetes-caused foot cracks. She encourages students to work on projects to solve problems from their personal lives. The dermatological shoe project, for example, was inspired by a student who wanted to help his mother.

A pharmaceutical company in Brazil is interested in commercializing the pigskin technology, and another company is interested in the fertilizer, she says.

Vitals

▸ Hometown: Franca, Brazil

▸ Education: BS, MS, and PhD, University of Campinas

▸ Current work: Teacher and research supervisor, Professor Carmelino Corrêa Júnior Technical School

▸ Proudest accomplishment I’m happy to have the opportunity to pass forward a little of my knowledge to my students. Knowledge is the only thing nobody is able to steal from us.

C&EN spoke with Félix de Sousa about her path in chemistry and the work she is doing now. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you pursue science and chemistry in particular?

The desire to study chemistry came since I was very little. I was born in a house inside a tannery, where my father worked for over 40 years. His financial situation was quite dire, and when he married my mother, his boss let them live in a little house in the inside area of the tannery. My siblings and I were raised there and were known in Franca as the “smelly children from the tannery.” Our friends almost never went there because to get to the house you had to go through the workshop, which smelled horribly. Tanning is an extremely stinky activity.

But in the tannery, I also saw chemists working. Their white coats and the dyes they handled really caught my attention and made me fall in love with chemistry.

You had a harsh childhood but didn’t give up on education. What kept you going?

Growing up, I studied in a public school at the city center. There were many children from affluent people studying there, and the classes were sorted by the students’ social status. Class A was the richest. I used to study in the last class, F. In that school, I understood what racism and exclusion were: I heard that people like me couldn’t succeed in life. I was bullied and felt so much shame that I sometimes didn’t want to go back to school.

But the wisdom of my parents saved me. Even being semiliterate, my father used to say I had to keep going to school and be the best in my class, that I should study hard, succeed, and show my bullies they were wrong about me.

So at age 14, I passed the entrance test to the Universities of São Paulo and Campinas and the Federal University of São Paulo. My teachers told me the best chemistry course in the country was in the University of Campinas, so that was my choice. Students in Brazil attend public universities for free, but it was still hard to cover living expenses in the first semester. A junior research grant covered my finances from the second semester on.

You could have gone on to work in a renowned university or research center. Why did you return to Franca?

It was my dream to teach and research in a big university. But my mother became ill. Also, my sister, a mother of four, and my father had died not long before. So I came back to help and saw this call for a teacher at the school I currently work in to teach a technical course in tanning.

The school is in the outskirts of the city because it runs a technical course in farming. The neighborhood is dominated by criminal groups, drug trafficking, and prostitution. It is not uncommon that students get involved in these activities to bring money home. When I first started there, school evasion was high and lack of discipline rampant. It was quite hard to get students engaged.

We developed a research project to give incentives and grants to hard-to-reach students. It was a way to keep them busy with something that could take them out of prostitution and drug trafficking, and it worked. In a decade, I mentored 40 students. Eight went on to work as technicians, and 32 went to university to study chemistry. The worst students, when given the opportunity, will find all the dormant talent they have inside them and end up being the best students in class.

What projects are you and your students working on now?

We’re developing a flame-resistant fabric that can be used in firefighter uniforms, like the ones used in the US, but not as expensive, so Brazilian firefighters can wear them. We treated cow skin with waste Styrofoam extracts to make it impermeable and nonflammable. The idea came from a student whose uncle, a firefighter, had his back burned at work.

Other projects include antimicrobial fabrics for nurses’ and doctors’ uniforms, as well as patient pajamas and hospital bed linen in order to avoid hospital infection as much as possible. We’re also working on antimicrobial wall paint for hospital bedrooms and halls. This idea also came from a student whose aunt died from a hospital infection, even though she was admitted into hospital for a minor issue.

Meghie Rodrigues is a freelance writer based in Brazil.

UPDATE

This story originally indicated that Félix de Sousa did postdoctoral research at Harvard University. Brazilian media publication O Estado de S. Paulo subsequently raised questions about her Harvard affiliation. Félix de Sousa now says that she discussed a project with Harvard chemistry professor William Klemperer and visited his lab but did not work there for a sustained period of time. Klemperer died in 2017. Brazil’s National Council for Scientific and Technological Development tells C&EN that it funded Félix de Sousa to do postdoctoral research at the University of Campinas in Brazil. C&EN removed all references to Harvard from the story on May 21, 2019. C&EN revised the story again on June 3, 2019, to reduce the number of patents that Félix de Sousa holds.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter