×

CEN's 2020 Trailblazers

Paula Hammond: Drug delivery pioneer

Oluwatoyin "Toyin" Asojo: Rare-disease drug hunter

Laura Dassama: Sickle cell fighter

Cordell Hardy: Industrial innovator

Vernon Morris: Atmosphere investigator

Isiah Warner: Materials maestro and mentor

Malika Jeffries-EL: Semiconductor materials maven

Squire Booker: Catalysis champion

Jamel Ali & Patrick Ymele-Leki: Biofilm-busting duo

Carl Bonner: Jack of all chemistries

Cato Laurencin: Tissue regenerator

Kristala Prather: Synthesis warrior

Samson Jenekhe: Polymer powerhouse

Davita Watkins: Supramolecular chemistry sleuth

Karen Akinsanya: Strategic drug discoverer

Lynden Archer: Entrepreneurial educator

Etosha Cave: CO2 converter

Kimberly Jackson: Cancer slayer

Thomas Epps & LaShanda Korley: Upcycling champions

Sherine Obare: Interdisciplinary icon

Historical profiles

Contributors

C&EN's 2020 Trailblazers Celebrating badass women entrepreneurs in chemistry

Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Atmospheric Chemistry

Movers And Shakers

Vernon Morris has uncovered the secret chemistry of atmospheric dust

This chemist has expanded field research opportunities for people of color

by Ashley Smart, special to C&EN

February 22, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 6

There’s a whole hidden molecular world floating around above our heads, and atmospheric chemist Vernon Morris is determined to demystify it. Morris, previously a professor at Howard University and now a director at Arizona State University’s New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, has spent his career illuminating the surprising chemical and physical properties of atmospheric dust. In doing so, he’s left an indelible mark in fields such as climate science, meteorology, satellite imagery, and public health.

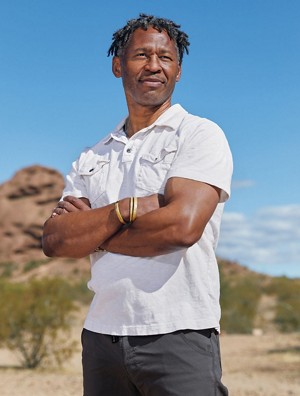

Credit: Matt Martian

Vernon Morris

Vernon Morris

Hometown: 10 cities (US Air Force brat)

Education: BS, Morehouse College, 1985; PhD, Georgia Institute of Technology, 1991

Current position: Director, School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences, New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, and professor of chemistry and environmental sciences, Arizona State University

Book that made an impact on him: The Souls of Black Folk, by W. E. B. Du Bois. It allowed me to better understand American culture and society, put into words many of my experiences and thoughts, and revealed that Black people had possessed this deeper insight for centuries.

Best professional advice he’s received: Trust in yourself, but put in the work to justify that trust.

But Morris’s chemistry career almost never got off the ground. It was only because of a chance encounter with renowned chemist Henry McBay that he even considered majoring in chemistry, Morris recalls. Four decades ago, as an undergraduate at Morehouse College, he was taking a shortcut through the chemistry building when he ran into McBay. “I was trying to go get a job to pay for some school debts,” Morris says. “And [McBay] said, ‘Look, if you major in chemistry, I’ll take care of that.’ ” McBay helped Morris land a job in an atmospheric chemistry lab, and he’s been enthralled by the subject ever since.

Years later, after Morris had joined the faculty at Howard, serendipity struck again, this time in the form of an opportune collaboration. A colleague, satellite oceanographer Roy Armstrong, approached Morris with a problem: his satellite images were being obscured by clouds of dust originating from the Saharan desert. To extract the noise, he needed help determining the dust’s properties.

Morris suspected that those properties were probably constantly evolving—his chemistry instincts told him that reactions and physical interactions with the atmosphere were probably transforming the dust midflight as it traveled from the Sahara over long distances. To test that notion, the two scientists boarded a small vessel and sailed off the coast of Puerto Rico to harvest dust samples at various locations.

“I was seasick all the time,” Morris says of that first voyage. “But we were getting some really interesting data.” They found that the dust’s properties varied from one side of the island to the other. The properties were changing over time, just as Morris had predicted.

Those preliminary data provided the impetus for what would become the Aerosol and Ocean Science Expeditions, or AEROSE, a first-of-its-kind series of transatlantic research cruises to track and characterize the properties of Saharan dust. With Morris as chief scientist, field expeditions produced data that have proved instrumental in validating satellite measurements, refining climate and weather models, and answering fundamental questions about atmospheric chemistry. These data have clarified, for instance, dust storms’ effects on ozone chemistry and hurricane formation. And they have revealed thriving airborne communities of bacteria and fungi living on the dust particles’ surfaces. Morris has found that these microbes can aggravate asthma and other health conditions when the dust finally settles back to earth.

[Morris] provided kind of a fuel to bring more people together and to create a more supportive community. It’s almost like he laid the path, or the template, for the next generation of young scientists to continue.

Gregory Jenkins, atmospheric scientist, Pennsylvania State University

Gregory Jenkins, an atmospheric scientist at Pennsylvania State University and a former colleague of Morris’s at Howard, points out that the AEROSE campaigns have also helped usher in a diverse new generation of atmospheric scientists. On the 12 AEROSE cruises conducted since 2004, Morris has brought along dozens of students from Howard and other institutions serving people of color.

“Quite often, students and faculty members of color are excluded from these kinds of big field projects,” Jenkins says. “I always have felt that the field campaigns, if we could get students from underrepresented groups on those, it would be potentially a game changer.” Indeed, Morris and others proudly point out that over the past decade, Howard’s graduate program in atmospheric science, which Morris helped create, has produced roughly one in every two Black atmospheric science PhDs minted in the US and roughly one in every three Latino PhDs.

As Jenkins sees it, these successes reflect Morris’s knack for community building and his drive to make atmospheric science a more inclusive field. He “provided kind of a fuel to bring more people together and to create a more supportive community,” Jenkins says. “It’s almost like he laid the path, or the template, for the next generation of young scientists to continue.”

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter