Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Climate Change

The race to preserve Earth’s historical climate record—its ice

As climate change threatens Earth’s glaciers and ice sheets, climatologists and chemists are banking ice core samples for the future

by Katherine Bourzac

June 15, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 23

Credit: Sarah Del Ben/Fondation UGA | Engineers associated with the Ice Memory Project prepare to drill an ice core from the Col du Dôme glacier in the French Alps in 2016.

Climatologist Lonnie Thompson’s voice is still full of wonder when he talks about seeing the Quelccaya Ice Cap for the first time. “It was so beautiful, like looking at layers on a cake,” he says of looking up at an icy cliffside in 1974. Like many mountain glaciers, Quelccaya comprises stacked layers, each one representing a year of compressed snowfall and a potential wealth of historical information about climate variations. The Ohio State University scientist had traveled to the ice formation, located in the Andes Mountains in southern Peru, to collect samples.

In brief

Ice cores—cylindrical samples drilled from glaciers—have played a central role in helping chart the past climate of Earth and have even helped trace human history and present-day pollution. But climate change puts these precious records at risk: many of the world’s glaciers and ice sheets are melting at an accelerating rate. While chemists continue to develop more sensitive methods to read the chemical messages in the ice, glaciologists are now rushing to study and store ice cores from vulnerable formations. Their goal is to protect this unique source of data about Earth’s natural history for future scientists.

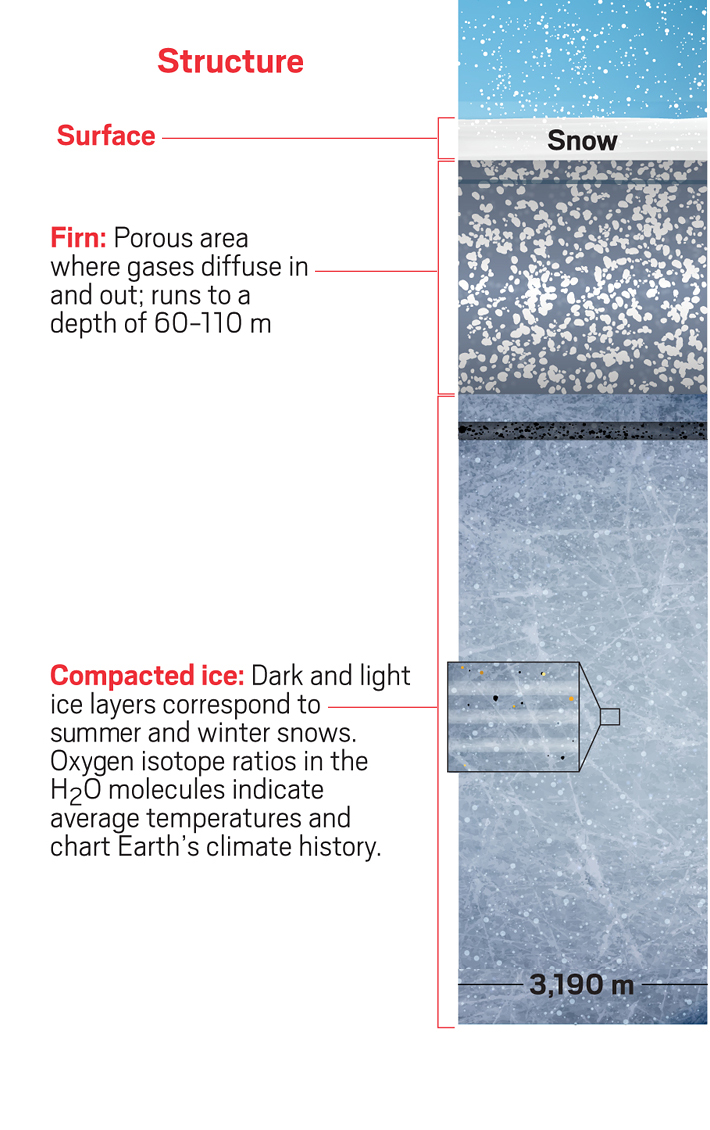

As snowflakes fall and get compressed into ice, they trap gases and compounds from the air, layer by layer building up a time-stamped record of the atmosphere’s chemical composition. Over time, the snow turns into ice formations that scientists can drill into to retrieve ice cores. Layers in these cylinders of ice, like tree rings, tell a scientific tale that stretches far into the past—in the case of ice, nearly a million years. Ever since researchers first started drilling deep ice cores in the late 1960s, these samples have played a central role in helping chart the past climate, or paleoclimate, of Earth. Isotope data from the ice cores Thompson and his team drilled at Quelccaya, for instance, provided the first long-term chart of temperature variations in the tropics—and inspired similar expeditions to high mountain glaciers around the world.

Because of climate change, today these unique records are at risk of disappearing. Each time Thompson and a growing team of collaborators have gone back to Quelccaya over the years, the ice cap was smaller. With the exception of Antarctica and much of Greenland, the world’s glaciers and ice caps are melting at an accelerating rate; some, including Quelccaya, may be gone in decades. And before that happens, surface melt will move down into the glaciers, smearing out their beautiful cake-like layers to erase thousands of years of history.

To get as much as they can from this precious resource, glaciologists are now rushing to study and store ice cores from vulnerable glacial formations in Peru, Tanzania, the Arctic, the Alps, and other places around the world. As the planet warms, says Carlo Barbante, an analytical chemist at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, “we are in a hurry.”

Earth’s temperature chart

Ice core research as it’s done today has a somewhat dubious beginning in a secret US military base at the Northwestern Greenland Ice Sheet. In 1959, during the Cold War, military workers there used scientific research as cover and dug the base 8 m down into the ice. With its proximity to the Soviet Union, Camp Century was intended to hide nuclear missiles that would be transported in and out of a buried warehouse via a subsurface railway.

By 1967, however, the scheme—which bore the code name Project Iceworm—was scrapped because the snow tunnels at the base were unstable. But before it was shut down, researchers at the site had performed foundational research in climatology. In 1966, they drilled a 1,390 m long ice core and used it to trace Earth’s temperature over the previous 100,000 years (Science 1969, DOI: 10.1126/science.166.3903.377). The drill used by the scientists was then shipped to Byrd Station in Antarctica, where in 1968 a team dug 2,164 m deep, to the bottom of the ice covering the land there. Scientists from the Soviet Union carried out similar research at Vostok Station in Antarctica, drilling ice cores at the coldest place in the Southern Hemisphere (the Antarctic Pole of Cold) throughout the 1970s. Prior to these experiments, scientists had not had access to high-power, specialized drills, and only dug holes tens to hundreds of meters deep in glacial ice, yielding limited information.

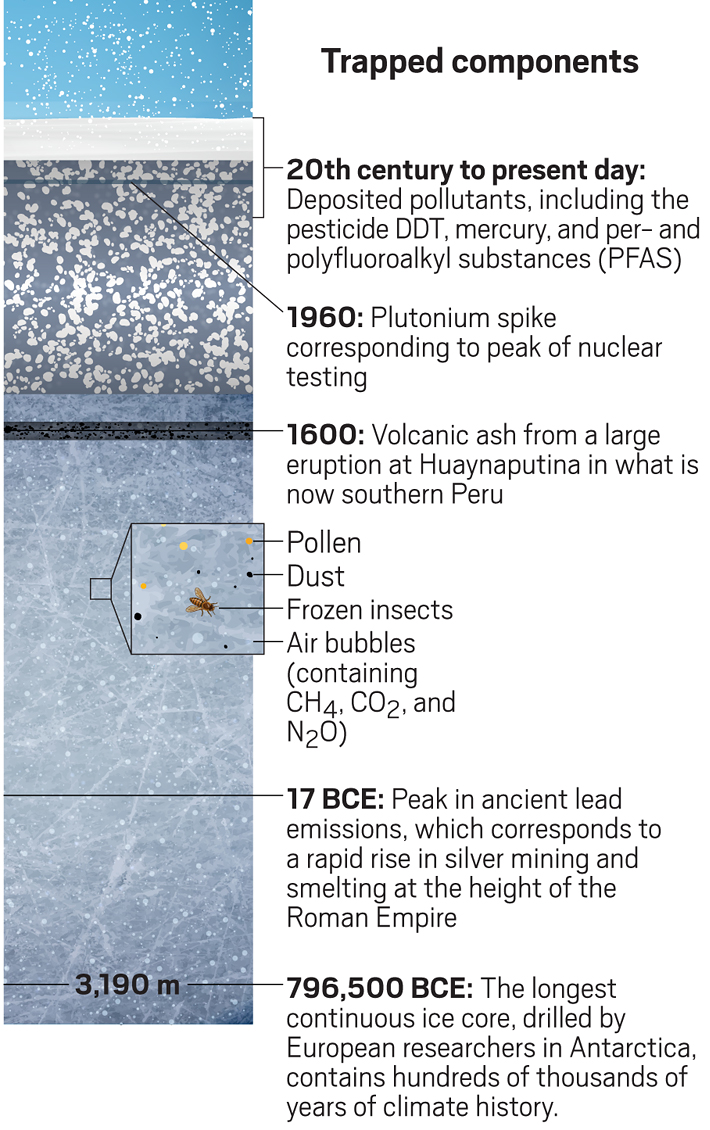

The snow that falls annually on the planet’s ice sheets and glaciers contains much more than water. “Give me an ice core, and I can tell you what was in the atmosphere thousands of years ago,” Barbante says. Those components can include dust, pollen, pollution, ash from distant volcanoes, and even microbes. Over decades, gases diffuse in and out of pores in the accumulated snow. As the snow gets compressed into solid ice, those pores turn into bubbles that trap carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and more.

Early work on polar ice helped glaciologists figure out how the layers in ice cores correlate with the passing of hundreds of thousands of years’ worth of seasons. Researchers would saw samples from the cores one layer at a time and melt them, finally examining the ratio of oxygen isotopes in the water. This ratio provides a proxy for past temperatures, one climatologists still use to this day.

“Most of the water in the world has oxygen-16,” explains Bradley Markle, a climate scientist at the California Institute of Technology. But some portion of the world’s H2O molecules contain the less abundant, heavier isotope, oxygen-18. Before atmospheric H2O from low and midlatitudes arrives at the poles, it travels the world, and some is lost to precipitation. Finally, when it reaches those cold, dry regions, it gets wrung from the skies in large snowstorms. “As the water moves from a warm place where it’s evaporated out of the ocean to a cold place like a glacier, the heavier stuff preferentially falls out,” Markle explains. That means during a cooler-than-average year on Earth, by the time the water comes down as polar snow, it will have less of the heavier isotope. Ice from cooler years is thus marked by relatively low 18O:16O ratios, and ice from hotter years by relatively high 18O:16O ratios.

Such analyses of polar ice cores have been pivotal in establishing the story of the planet’s climate over the past million years and how human activity has changed it. The oldest continuous ice core, taken from Antarctica, holds 800,000 years of records. (Homo sapiens emerged a mere 300,000 years ago.) European researchers working on a project called Beyond EPICA plan to go back even farther in time. They have chosen a site in Antarctica where, during this decade, they hope to drill a continuous, 1.5-million-year-long core.

Ancient ice from Antarctica and Greenland can give researchers an overall picture of the planet’s past and present climate—and these formations, located in the coldest places on Earth, are not at imminent risk of melting. But for the regional details that illuminate the climate in the places where most people live, scientists have to look elsewhere.

Between the poles

In the early 1970s, when Thompson was working on his PhD, he began wondering what might be locked in the ice in high mountain glaciers between the world’s poles. This area hadn’t yet been drilled for ice cores as the poles had. He thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to connect that evidence with something in between?”

Because Earth is a sphere, almost half its surface area is located in the tropics. The tropics play a major role in the climate—monsoons and El Niño patterns arise there.

Thompson found Quelccaya in a box of aerial photos of glaciers. It took a decade to figure out how to drill the 5,670 m peak. One trip to Quelccaya, in 1976, was plagued by mishaps. The ice cap was a 2-day journey on foot from the nearest road; neither horse nor helicopter could transport the heavy drill and generator Thompson and his teammates brought with them.

Like many glaciologists who work at high elevations, Thompson is a combination mountaineer, chemist, and engineer. So he realized he could replace the heavy generator with solar panels, which were a relatively new technology at the time, enabling his team to build a lightweight drill that could be carried up to the ice cap.

In 1983, the team finally got its drill to the top of Quelccaya and took two cores. The scientists cut out samples with handsaws and meted them out into 6,000 bottles, which they carted out on horseback and shipped to Willi Dansgaard at the University of Copenhagen for analysis.

Data from Quelccaya have filled in the historical picture of Earth’s tropical climate. They have also helped anthropologists study how annual rainfall and drought patterns tracked with the rise and fall of ancient South American civilizations—including the Tiwanaku civilization, which peaked sometime before 1000 CE.

Since this first expedition, cores drilled from midlatitude glaciers in other places—including in the Alps and Himalayas, and on Mount Kilimanjaro—have provided their own regional insights into climate and human history. “Those ice bodies preserve everything that is in the atmosphere, and they do it at the latitudes where human civilization developed,” Thompson says.

As analytical technology has developed, environmental chemists and climatologists have been able to ask more sophisticated questions of the ice. Analysis has gotten much easier than it was for climatologists working on the first ice cores in the 1960s, says Joseph McConnell, a hydrologist at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada. Instead of individually sawing out each layer, cleaning off the resulting slice, melting it, and analyzing it, researchers can now take measurements of the chemicals trapped in the ice during a continuous melt-measure process back in the lab.

McConnell carries out such a continuous process with a system he and his team developed that melts and analyzes ice cores simultaneously. Using this method, the researchers can process 6 m long cores in about 2 h. McConnell’s system holds an ice core vertically over a heated ceramic melter plate. Channels in the plate capture water only from the innermost section of the core. Meltwater is funneled to a cavity ring-down spectrometer, which continuously measures its chemical contents. This system provides more data in one day than students were able to generate during their entire PhDs, McConnell says.

One key marker of the passing of summer and winter seasons is the water isotope ratio. When doing continuous measurements, “you can watch chemical levels going up and down and count the cycles like you would a tree ring,” McConnell says. Annual marks in an ice core can often even be seen with the naked eye: thicker layers of winter snow are denser and darker in color; smaller, lighter colored streaks represent summer snow, which is more porous—far less of it falls. These oscillations mark the years.

Advertisement

“Every once in a while you see a volcano,” McConnell says. Bands of ash from volcanic eruptions and radiation from atomic bomb tests show up as isochrons, time markers that are the same in samples taken from anywhere around the world. And McConnell’s analyzer can see them in precise detail. His group was able to chemically detect plutonium levels in an ice core for the first time, instead of just observing the radiation. The researchers found one part per quadrillion of 239Pu in ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland, deposited there by nuclear testing in the mid-1960s (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01108).

Ice cores can trace other human activity, too. McConnell’s team has made high-resolution measurements of lead pollution in the Arctic that serve as a record of silver production from 1000 BCE to the present. Silver mining and smelting operations—both of which boomed in times of economic prosperity in the ancient world and waned in troubled times—caused lead emissions that were transmitted through the atmosphere around the world, including to the Arctic. These silver ores were rich in lead, and the toxic metal was used in its extraction. Ice core lead levels are therefore a marker of ancient economic activity, war, and plague extending from the Bronze Age to today (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1721818115). “You can see the Greeks and the Romans, plagues like the Black Death,” McConnell says.

“There’s no way we could have ever conceived you could get so much information from a glacier,” Thompson says. “They are fascinating archives,” he adds, and “they are disappearing rapidly.”

Disappearing ice

The world’s ice is melting at an accelerating rate. A recent study based on satellite measurements from April 2002 to September 2019 estimates that the planet’s ice sheets and glaciers (excluding the most stable ones in Antarctica and on the periphery of Greenland) lost a tremendous amount of ice during that period: a total of 4,540 gigatons, which is the equivalent of 13 mm of sea level rise. And the loss accelerated by an average of about 5 gigatons per year (Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, DOI: 10.1029/2019GL086926). The greatest losses were in Alaska, the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, and the southern Andes.

And if that’s not enough bad news, before the ice disappears, its record is damaged. As meltwater from the surface of an ice formation seeps downward and refreezes, the temperature record will “now have material showing up from another year,” says Alison Criscitiello, director of the Canadian Ice Core Lab at the University of Alberta.

Criscitiello is drilling ice cores from the Canadian High Arctic, where more recent records—from the industrial revolution to the present—are starting to get washed out. Like Quelccaya cores, ice from the Canadian Arctic provides a unique regional record, in this case, one that reflects climate variability in the Pacific.

Not only is surface thaw ruining climate records, it’s also affecting people’s water supplies. Researchers have estimated that Quelccaya will stop accumulating ice and begin shrinking in just 30 years (Sci. Rep. 2018, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-33698-z). People who rely on the ice cap’s banked water to fill their rivers are likely to experience water shortages, both in the municipal water supply and in the water that drives hydropower at the Machu Picchu Hydroelectric Power Plant.

Another mark against glacial melting is the contaminants unleashed by the process. Pollutants are transported through the atmosphere and laid down in the snow in even the most remote areas, says Kimberley Rain Miner, a climate scientist at the University of Maine. Ice cores from Mount Everest contain toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Glaciers in the Alps contain the pesticide DDT. Far from pristine, these remote formations are “almost like a landfill of legacy pollutants,” Miner says. And as the ice melts, those pollutants are “re-emitted in places where they were never used in the first place,” she says.

When the glaciers recede, this important water source will be gone. At the same time, environmental chemists will lose a key tool for tracking pollution transport both historically and in the future, Miner says. And it will be harder for atmospheric chemists to trace back which countries are violating international treaties that ban persistent organic pollutants such as DDT. “We’re losing this incredible repository of data that covers all of human history, and before,” Miner adds. But it’s not too late to bank samples.

What's in an ice core?

After snow falls on the world’s ice sheets, it eventually becomes compacted into a porous layer called firn. At a depth of about 60 to 110 m, depending on the site, the firn transforms into solid ice permeated with trapped air bubbles. Ice cores contain a rich historical record of the atmosphere, from modern pollutants to ancient pollen and bacteria to prehistoric CO2.

Frozen heritage

Ice banks around the world—in Alberta, in Colorado, in Grenoble, France, and elsewhere—keep these precious records in large freezers. Thompson and his collaborators keep their cores in the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at the Ohio State University. Some of the samples there are rare, coming from ice caps that have either disappeared or have melted to the point where they can no longer be reliably drilled. The question about these samples is when to analyze them. “Is it better to use it 20 to 30 years from now, when there will be new techniques we haven’t thought of?” Thompson asks. Or would it be better to analyze it now to learn as much as possible today? The ice Thompson and his team collected from Mount Kilimanjaro is particularly precious because there’s not much of it left in storage, and the dormant volcano’s ice cover has shrunk by 85% since 1912.

Thompson says deciding how to mete out finite, irreplaceable ice core samples for research is “a balancing act.” Climate change is already altering life on Earth, and today’s scientists have inarguably urgent questions about what’s going to happen to our planet. The ancient ice holds answers. Insights about the past climate—how temperature, greenhouse gas levels, sea level rise, ice sheet dynamics, and more are interlinked—help scientists model what will happen in the future.

More sophisticated analytical techniques of the future are likely to give scientists a lot more information from the same precious ice. Barbante notes how much analytical techniques have improved during his own career. When he looks back at the lengths he had to go—sawing and cleaning ice slices, for instance—to study ice cores even as recently as the 1990s, it’s “really ridiculous,” he says. He hopes today’s technologies look similarly primitive to future scientists. Thirty years from now it might even be possible to analyze ice cores without melting them, Barbante says.

Barbante had for years been ruminating over the idea that our ice record is melting while analytical techniques improve. In 2015, he found a kindred spirit in colleague Jérôme Chappellaz, director of the French Polar Institute Paul-Emile Victor. Over beers, the two came up with the Ice Memory Project, which will drill ice cores and bank them in Antarctica for future scientists.

Scientists contributing to the Ice Memory Project will drill two or three cores at each site, analyze one to see what’s there, and send the rest to the project for storage. The Ice Memory team started with Col du Dôme glacier at the foot of Mont Blanc in the French Alps, and contributors have so far drilled at the Illimani glacier in Bolivia, the Elbrus glacier in the Caucasus Mountains in southern Russia, and the Altai Mountains, which border Kazakhstan, Siberia, China, and Mongolia. Until the Ice Memory team completes its storage facility, the cores will continue to be stored in lab freezers. Drilling at four sites may not sound like much, but each complex scientific expedition takes years to plan and execute.

Even though today’s glaciologists have lightweight drills and other high-tech equipment, these missions are extremely complicated, expensive, and can be canceled due to unsafe weather coming on suddenly at high altitudes. The Ice Memory team scrapped plans to core Kilimanjaro in January, and it’s unclear when they will be able to reschedule, due to the COVID-19 pandemic; another expedition in the Alps couldn’t go forward because of dangerous weather conditions.

Barbante hopes to start moving “heritage” ice cores to the Ice Memory facility in Antarctica for long-term storage in the next five years. It’s located in East Antarctica, near a research station operated by France and Italy. “It’s literally in the middle of nowhere, where the average temperature is –52 °C,” Barbante says. Because the facility is a natural freezer, operating costs will stay low, and the remote location means the cores should be safe from most human interference.

So far the team has done preliminary tunneling tests to demonstrate that they can build the facility—a kind of benign Project Iceworm. They used a snowblower attached to a snowmobile to clear an area, then laid down “a big rubber sausage” filled with air, Barbante explains. The scientists covered the sausage with snow, sintered the snow to make a compact roof, and removed the sausage, leaving what Barbante calls “a perfect tunnel under the snow.”

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization has endorsed the Ice Memory Project, but its unusually future-focused nature has made it difficult to find funding, Barbante says. Science agencies want to invest in science happening today—not in gathering material for projects that will happen 30 years from now. To move forward, Barbante says the team is seeking private funding.

Barbante is optimistic about the future. Even if the project has to drill cores that are partially damaged by melting caused by climate change, future scientists might still be able to analyze them with more sophisticated techniques, he says. For now, he and other glaciologists are eager to get back into the field to collect precious ice, as soon as COVID-19 restrictions are lifted and expeditions are considered safe. “We are not just a science project,” he says. “We are bringing forward a heritage for the future.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter