Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Persistent Pollutants

Checking drinking water for PFAS and lithium

US EPA proposes that utilities monitor 30 chemicals

by Cheryl Hogue

February 24, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 7

Public water systems in the US would have to monitor their drinking water for the presence of 29 environmentally persistent synthetic compounds and of lithium under a proposal the Environmental Protection Agency released Feb. 22.

![Drawing shows the chemical structure of 2-[(8-Chloro-1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8-hexadecafluorooctyl)oxy]-1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethanesulfonic acid. Drawing shows the chemical structure of 2-[(8-Chloro-1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8-hexadecafluorooctyl)oxy]-1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethanesulfonic acid.](https://s7d1.scene7.com/is/image/CENODS/09907-polcon1-chlor?$responsive$&wid=300&qlt=90,0&resMode=sharp2)

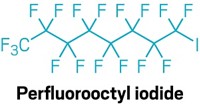

The 29 compounds are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that are either sulfonic or carboxylic acids, some with ether or sulfonamido groups (four examples shown). Exposure to a number of PFAS is linked to reproductive, developmental, liver, kidney, and immunological problems.

The alkali metal lithium occurs naturally in some groundwater, including brines pumped from oil and gas wells. Exposure to lithium can impair thyroid and kidney function.

About 45% of US public-supply water wells contain levels of lithium that potentially could pose a risk to human health, according to a US Geological Survey study released in February (Sci. Total Environ., 2021, DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144691).

The EPA does not currently limit the amount of any PFAS or lithium in drinking water. However, the agency announced in January that it officially determined it needs to regulate two toxic PFAS that contaminate drinking water supplies across the US, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). Formerly used in fire-fighting foams, PFOA and PFOS are no longer manufactured in the US.

Under the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Act proposal, utilities would monitor for the presence and amount of the 29 PFAS and lithium from Jan. 1, 2023, to Dec. 31, 2025, and report their findings to the agency. The EPA would then use the data to determine whether federal legal limits are needed on any of these substances in drinking water to protect public health. Congress could speed up the regulatory process by passing legislation requiring the EPA to set limits on the chemicals in drinking water.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter