Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

Dragonfly larvae serve as biosentinels for mercury pollution

Citizen scientists use the insects to investigate freshwater habitats in national parks

by Ariana Remmel

July 30, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 30

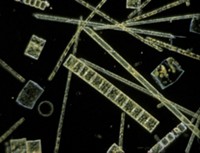

Mercury wreaks havoc in freshwater ecosystems, but monitoring the risk to wildlife can be challenging. Researchers have now shown how dragonfly larvae act as biosentinels for toxic mercury. When inorganic mercury enters the food chain, it gets converted to methylmercury, a toxin that causes neurological damage. Because inorganic mercury levels don’t always correlate with bioaccumulation of methylmercury, researchers have to sample living animals to understand poisoning risk in the environment.

“It’s very hard to find the same organism in water bodies across a broad landscape,” says Collin Eagles-Smith, an ecotoxicologist with the US Geological Survey. But dragonfly larvae—predators that accumulate mercury—are widely found in freshwater ecosystems across the continent.

With the help of more than 4,000 citizen scientists over 10 years, Eagles-Smith and his team collected dragonfly larvae from 100 national parks (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01255). They found that mercury levels detected in larvae correlated well with other organisms sampled at the same time and could be compared across sites. “That tells us we can use dragonfly [larvae] mercury concentrations to predict what’s in fish and other wildlife,” Eagles-Smith says.

The team also showed that biotic factors affect how much of the available inorganic mercury enters the food web. “The processes that generate methylmercury play a very important role in driving risk of exposure across the landscape,” he says. Eagles-Smith hopes this research will inform management techniques for mitigating mercury risk in sensitive habitats.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter