Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Coatings

Chemistry In Pictures

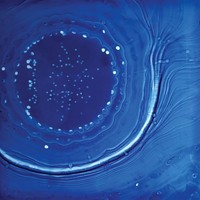

Chemistry in Pictures: CO₂ capture surprise

by Craig Bettenhausen

April 7, 2022

Chemist and inventor Kevin A. McIntyre set out to develop a cheaper way to replicate iron gall printing, which combines iron and tannic acids to create a permanent, waterproof pigment that starts off bold and darkens with age. Iron gall was the dominant ink chemistry in Europe from the 5th to 19th centuries but fell out of favor as options that were less corrosive to paper emerged. Antiquarians and historical reproduction artists still use iron gall to mimic the aesthetics and colors of that 1,400 period, but it can be expensive and incompatible with modern printing methods. McIntyre’s approach expands iron gall into inkjet and 3D printing, as well as other delivery methods, like the Prussian blue formulation coating clay balls and other objects in the photos above, mimicking the slow deepening of the retro ink. But it turns out the material absorbs CO2 out of the air as it darkens. “While originally developed as a novel printing solution,” McIntyre says, “My technology creates a unique tannin-mineral surface that acts as a passive CO2 collector.”

Submitted by Kevin A. McIntyre

Do science. Take pictures. Win money. Enter our photo contest here.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter