Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Coatings

What’s after PFAS for paper food packaging?

As US states ban the use of ‘forever chemicals’ in these products, papermakers are turning to other materials—without disclosing what’s in them

by Cheryl Hogue

October 3, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 36

Credit: William Ludwig/C&EN/Getty

In the 1960s, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, the company that popularized Teflon-brand fluoropolymer coating for nonstick pans, started looking for new markets that might benefit from the strong fluorine-carbon bonds in fluorochemicals. The company began to sell stain-resistance treatments for carpets and fabrics. It also found success with fluorochemicals that help food packaging paper and paperboard resist grease and water.

In brief

Fluorochemicals have long been used as a treatment to make paper wraps for burgers and other foods resist grease and water. Now, several US states are banning the use of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in fiber-based food packaging. At the same time, health and environmental advocates are pushing restaurant and grocery chains to stop using wraps, paperboard, and fiber containers with added PFAS. Papermakers are rolling out new products to meet this demand—but what’s taking the place of PFAS is hidden behind a wall of corporate confidentiality. Third parties are stepping in with tools to examine the safety of PFAS alternatives while protecting trade secrets.

For decades, scores of these per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) gained approval from regulators in the US and elsewhere. PFAS are extremely good at rendering paper wraps and containers impervious to grease and moisture oozing from hamburgers, french fries, and other foods.

Today, fast-food chains and grocery stores are realizing that fluorochemicals are not always the wonder materials they were made out to be. PFAS are environmentally persistent, and some are toxic. And studies finding that PFAS in paper wraps and boxes can migrate into food have piled up in recent years (Foods 2021, DOI: 10.3390/foods10071443).Because of those concerns, many food companies are switching from single-use containers and wraps made with PFAS to packaging without these “forever chemicals” as ingredients.

But the identities of the chemicals or coatings that companies are switching to are typically proprietary information. Citing competition, most paper and packaging companies won’t discuss the products they’re making. Supermarkets and restaurants can find third-party assurances that the paper food ware they buy has no added PFAS. Yet they don’t generally know what substances are being used instead.

“Not only are these specific chemicals that we want removed from our packaging materials; we also want to make sure that we don’t introduce other hazardous chemicals” as alternatives, says Boma Brown-West, director of consumer health at the Environmental Defense Fund, an advocacy group. While in an ideal world, consumers would know what the replacement chemicals are, some organizations say such knowledge might not be as important as toxicity data, reviewed confidentially by third parties, showing that they are safer than the PFAS they replace.

A long history

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the first PFAS for coating paper and paperboard, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company’s Zonyl RP, in 1967. The company called the product, which repelled water and oil, a “paper fluoridizer.”

For the first time ever, PFAS were on food packaging. Over time, more companies entered this market with dozens of similar chemicals. In more recent years, as the biopersistence of PFAS became clear, chemical makers shifted from long-chain PFAS—such as Zonyl RP—to short-chain ones, which generally contain six or fewer carbons, for treating food packaging materials. Many researchers believe short-chain PFAS have less potential to bioaccumulate, though their toxicity is similar to that of their longer-chain cousins.

Then in 2020, the FDA announced that four chemical manufacturers were voluntarily phasing out the sale of 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol, one of the short-chain PFAS, for use in paper and cardboard food packaging. This substance degrades in the environment to form persistent and biologically active perfluoroalkyl acids.

Today, the FDA’s Inventory of Food Contact Substances, which lists materials the agency deems “demonstrated to be safe for their intended use,” contains about 50 fluorochemicals that are approved to be marketed in the US. All the fluorochemicals in the inventory received FDA approval between 2000 and 2020.

It’s unclear how many of them are still being sold for food packaging.

Pressure to shift from PFAS

Three main forces are moving food packaging makers away from PFAS, says Shari Franjevic of Clean Production Action, a Massachusetts-based organization that promotes green chemicals, materials, and products.

One push comes from state legislation enacted in Connecticut, Maine, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Washington that bans PFAS in food packaging, she says. Enhancing this movement is the European Union’s effort to restrict uses of all PFAS, Franjevic says.

A major US industry group is challenging efforts to phase out PFAS in products, including in food packaging.

PFAS-free options

“All PFAS are not the same,” stresses the American Chemistry Council, which represents chemical manufacturers, including makers of fluorochemicals. “It is neither scientifically accurate, nor appropriate, to group them all together by the entire class—especially when discussing the health profiles” of these chemicals, the trade organization tells C&EN in a statement.

Members of the ACC voluntarily agreed to phase out certain PFAS for use in paper-based food packaging, the group points out. But “for many PFAS uses, there aren’t alternatives,” it says.

Bypassing the policy debate, several US environmental and health groups are urging fast-food chains and other big purchasers to voluntarily switch to PFAS-free paper wraps and containers. These efforts are a second major force in the switch away from PFAS in food packaging, Franjevic says.

“Retailers are playing an incredibly important role in moving the marketplace away from these toxic ‘forever’ chemicals,” says Mike Schade, campaign director of Mind the Store, in a recent statement. Mind the Store is a program run by the research and advocacy group Toxic-Free Future.“With many thousands of pounds of PFAS in circulation due to their use in food packaging, we applaud those companies that commit to phasing out these toxics in food packaging.”

As of September 2021, eight fast-food and fast-casual restaurant chains—Cava, Chipotle, Freshii, McDonald’s, Panera Bread, Sweetgreen, Taco Bell, and Wendy’s—had committed to eliminate PFAS from food packaging by dates ranging from 2020 to 2025, according to Mind the Store. The group is asking for large retailers to eliminate toxic chemicals in products and packaging.

The campaign continues to target Burger King. The CEO of that chain’s parent corporation, Restaurant Brands International, announced at a shareholders’ meeting in June that the business is exploring alternatives to PFAS.

Compostability questions

A third factor driving the switch away from PFAS is the desire by purchasers of single-use food ware to move from plastic containers to compostable paper items. To the surprise of many of these buyers, some items sold as compostable were treated with PFAS, environmental advocates say. Researchers have found that these containers could release PFAS into the environment if composted (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00280).

Compostable products are certified in North America by the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI). This association sets standards for the breakdown of products that can be mixed with food scraps and yard trimmings in commercial facilities to produce compost. As of Jan. 1, 2020, the BPI has excluded products with added organic fluorinated chemicals from qualifying for its certification.

Because PFAS are persistent in the environment, traces of these compounds may be present in the wood or water used for making paper and in the final products, industry and environmental sources point out. Thus, manufacturers and activists are stressing the lack of added PFAS in products.

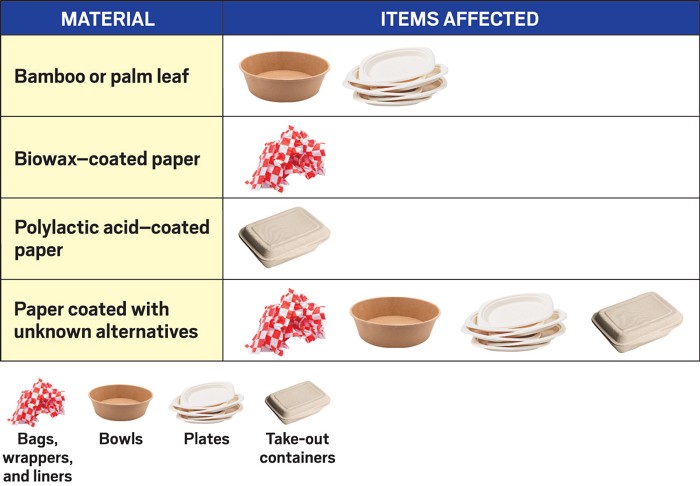

Industry is rapidly developing and deploying alternatives to PFAS for all types of single-use, fiber-based food ware. One strategy is to use mechanical means to make fibers denser—be they from wood, bamboo, palm leaves, or sugarcane waste—so they resist getting soaked through. “They squish the fibers really close together,” Franjevic says.

But mechanical means are often not enough to render fibers impermeable. Another approach is to employ a PFAS-free chemical barrier—either a surface treatment or a product added to pulp.

Some of the treatments that food-ware manufacturers rely on are disclosed in general terms and not down to the molecule. Examples include silicones, clays, waxes, and biobased plastics such as polylactic acid, according to information gathered by Clean Production Action. A 2017 report the Nordic countries compiled also lists treatment ingredients: starch, carboxymethyl cellulose, polyvinyl alcohol, wax, hydroxyethylcellulose, styrene-butadiene copolymer, the linear polysaccharide chitosan, alkyl ketene dimer, and alkenyl succinic anhydride.

Mum’s the word

Buyers of PFAS-free food ware are demanding evidence, such as BPI certification, that the paper goods they buy do not contain added PFAS. But purchasers still often don’t know what chemicals or technologies make these products resist grease and water.

Take the grocery store chain Whole Foods Market, which is focused on organic foods and environmental stewardship. Whole Foods learned in 2018 that the containers it bought for in-store use, such as at the salad bar, were treated with PFAS, says Jody Villecco, the company’s principal quality standards adviser. That December, Toxic-Free Future’s Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families program released a report showing that packaging for take-out foods sold by several grocery chains, including Whole Foods, likely contained PFAS.

“Through supplier surveys and product rtesting, we have discontinued or reformulated any food service packaging where it was disclosed or determined that PFAS may have been intentionally added,” Villeccor says in an email. “Whole Foods Market works with our packaging suppliers and a variety of non-profits, academics, and government stakeholders to avoid intentionalrly added PFAS.”

She adds, “In some instances, we were ablre to transition from product that was PFAS-treated to product that was non-PFAS treated and already commercially available. But in other instances, we had to work with our suppliers to reformulate food service packaging.”

While the grocery chain knows that the food ware it is buying now has no added PFAS, it doesn’t know what’s being used instead. “Disclosure of packaging components is not standard practice in the industry,” Villecco says.

C&EN contacted a number of companies that manufacture paper products for food packaging, asking them to discuss alternatives to PFAS and the safety of those additives. Most did not respond.

That’s probably because they’re either protecting the trade secrets of the businesses that make PFAS alternatives for treating food wraps and cartons—or they simply don’t know what’s in the treatments they buy from chemical makers or formulators, industry watchers say.

Companies that manufacture, formulate, and supply PFAS-alternative products are worried about protecting confidential business information, says Stacy Glass, executive director of ChemFORWARD, a nonprofit that promotes the use of safer chemicals.

“This space is supercompetitive,” she says of the market for water- and grease-resistant coatings without PFAS. These businesses want “to keep their secret sauce secret.”

“What’s actually being used is not well known,” agrees Franjevic, who manages Clean Production Action’s GreenScreen for Safer Chemicals, an online tool for companies to assess chemicals on the basis of their hazards and assist in the selection of safer substances.

For instance, Georgia-Pacific, maker of Dixie-brand paper products, manufactures food ware with its trademarked Soak-Proof Shield, which the company’s website says does not contain PFAS. In a fact sheet, Clean Production Action and Toxic-Free Future describe the material as “an acrylic-based coating that does not contain silicone.” Replying to a C&EN query about the material, a spokesperson for Georgia-Pacific says the information is “proprietary and confidential,” declining to discuss the matter further.

WestRock, which produces paperboard take-out containers, offers products coated with its proprietary EnShield treatment, which it says is fluorocarbon-free. WestRock did not respond to C&EN’s requests for comment.

Ahlstrom-Munksjö, a Helsinki-based manufacturer of paper and other fiber products, also won’t detail its PFAS replacements, but executives are willing to describe the broad contours of its replacement effort.

The company sells products to paper converters that custom cut the material into sheets or smaller rolls. The converters’ customers include delicatessens, fast-food chains, and other food service companies. Ahlstrom-Munksjö has multiple sustainability goals, including using locally sourced, sustainable wood supplies; using efficient water management practices; and avoiding hazardous materials.

Advertisement

Officials at Ahlstrom-Munksjö say they saw early signs of a growing market for food packaging made without PFAS and launched the Grease-Gard FluoroFree products in 2019. The company makes the lightweight, flexible paper at plants in Wisconsin and France. The paper is BPI certified.

“Part of the solution comes from the fiber we use” and how that fiber is processed, says Zack Leimkuehler, Ahlstrom-Munksjö’s vice president for technical solutions. Additives also play an important role, he says, and the company selects them with compostability in mind.

Some of the additives are plant based, says Jeff Murphy, Ahlstrom-Munksjö’s vice president for food packaging solutions. Others are food additives that are classified as generally recognized as safe by the FDA, he says.

Some of Ahlstrom-Munksjö’s manufacturing sites were making grease-resistant food packaging material a century ago, some 50 years before PFAS were approved for use on these products, Leimkuehler says. “What we are doing is going back to a lot of what we did in the past.”

California-based Zume, which makes molded-fiber food packaging, is bucking the trend by disclosing its PFAS replacement technology, which relies on products made by the specialty chemical company Solenis.

Zume began as a high-tech pizza company, developing robotic equipment to make pizzas that were baked on delivery trucks. But the boxes it used to package its pies affected the quality of the product. So Zume focused on making a better pizza box. And it succeeded, selling boxes to other pizza purveyors.

Zume then exited the pizza-making business in 2020 to focus exclusively on food packaging. It retooled its pizza-making robots to create fiber-based food packaging to replace single-use plastic items such as polystyrene clamshells.

“The big thing that we want to get rid of is single-use plastics,” says Pam Horine, Zume’s vice president of product research and compliance.

Zume once used short-chain PFAS to impart grease resistance to its US-made packaging, Horine says. But earlier this year, Zume and Solenis debuted a new method for making PFAS-free plates and bowls that relies instead on a biobased wax and new technology for manufacturing the containers. The wax and other additives are approved by the FDA for use as food-contact materials, she says.

“This is not just swapping out chemicals,” Horine says. “This is technological innovation.”

Lingering concerns

Advocacy group representatives warn that simply claiming that a food wrapper or container is made without added PFAS falls short of what’s needed for sustainability and safety. “Just being PFAS-free is not enough,” Franjevic says.

“We’re trying to avoid regrettable substitution,” says Brown-West of the Environmental Defense Fund.

She refers to swapping out one chemical because of health or environmental concerns and using another substance that performs well but may still pose hazards. For example, makers of thermal receipt paper stopped using bisphenol A, a well-researched compound that mimics estrogen, and started using the less-studied bisphenol S, which is suspected of having similar adverse health effects to those of bisphenol A.

Companies need to champion the use of chemicals for which data show they are safer than alternatives that perform the same function, Brown-West says.

To support chemical replacement efforts, some nonprofit organizations want to help food-ware makers take a critical look at the alternatives to PFAS. They are offering hazard comparisons or third-party certifications of the safety of the chemicals used in goods such as food packaging. These groups protect the identities of the substances and details of hazard data that could be valuable to competitors.

One such group is ChemFORWARD, which Glass cofounded to make hazard data about commercial chemicals and trade-named mixtures accessible while protecting trade secrets. This strategy allows companies to answer the question “Is it safe?” without disclosing to customers or the public the exact composition of ingredients, Glass says.

Apple, Nike, and several grocery chains are part of ChemFORWARD. They are seeking actionable information about ingredients—and possible alternatives—for their products while avoiding regrettable substitution, Glass says. ChemFORWARD promotes the use of circular materials, which can be recycled as raw material for the same use or composted safely. The group is focused on three sectors: packaging, consumer electronics, and personal care products.

Chemical manufacturers and formulators producing PFAS-free treatments can benefit from listing their products and toxicity data in ChemFORWARD’s database, Glass says, because they can demonstrate to potential customers the safety profiles of their products.

As part of the Safe + Circular Materials Collaborative, a partnership between ChemFORWARD and the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, some food packaging products are undergoing assessment for inclusion in the ChemFORWARD database, Glass says. For example, Ahlstrom-Munksjö is running its PFAS-free packaging materials through this process, according to a company spokesperson.

Other organizations, meanwhile, set publicly available criteria for making safety determinations for chemicals, Franjevic says. “While you won’t know the identity of all the chemicals in there, what you will know is that they meet certain minimum requirements for not being a regrettable substitute,” she says.

Clean Production Action, through its GreenScreen program, is developing a product certification that will deem an item as both free of PFAS and as using what the organization calls “preferred” chemicals. It will launch this certification later in 2021. GreenScreen already certifies certain firefighting foams as tested to be free of both PFAS and other chemicals of high concern to human health and the environment.

And in July, an international group of food service companies, advocacy groups, and technical experts launched an online tool called the Understanding Packaging Scorecard that looks beyond the chemicals used in production and assesses the entire life cycle of packaging materials. This tool is aimed at promoting a circular economy, in which discarded items become raw material for producing new goods.

For food containers, the Understanding Packaging Scorecard weighs factors such as the water needed to wash reusable dishes, the compostability of items made from paper or other fiber, and greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation, manufacture, sorting, and recycling of plastic containers.

Among its many criteria, the scorecard considers whether packaging contains ingredients that the European Chemicals Agency and the UN Environment Programme call “chemicals of concern,” including a number of PFAS.

The tool considers two aspects about chemicals of concern in food wraps and packaging, says Brown-West of the Environmental Defense Fund, one of the advocacy groups involved in the scorecard. One is whether any of these substances is intentionally added to food packaging and didn’t enter the product through environmental exposure. The other is the tendency of a chemical to migrate from food-contact materials into food or drinks.

All of the scorecards, databases, and other developments point to an expanding market for PFAS-free grease- and water-resistant technologies that are backed by safety data reviewed by third parties.

The identities of the ingredients in these food packaging products may remain protected by confidentiality claims.

But, Glass says, “We know there are good alternatives out there.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter