Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biologics

Hurricane Maria’s lessons for the drug industry

Keeping Puerto Rico’s pharmaceutical industry intact after the storm was a monumental task. A year later, companies consider how they can better prepare for the next natural disaster

by Lisa M. Jarvis

September 17, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 37

On the eve of Hurricane Maria, the most devastating natural disaster to hit Puerto Rico in a century, the staff at Amgen’s manufacturing site in Juncos had reason to feel confident that they would come out the other side of the storm unscathed. Sitting in the shadow of El Yunque rain forest, the site—Amgen’s biggest manufacturing facility worldwide—is typically protected from storms. And everyone on the island will tell you that hurricanes tend to swerve away from Puerto Rico, anyway.

Cover Story

Maria’s lessons for the drug industry

Not this time.

During the storm, the headcount was stripped back from its usual 2,700 to the bare minimum needed to run the critical manufacturing lines at Juncos. Still, with 158,000 m2 to cover, about 100 people were scattered across a few key buildings.

And they were busy: At 9 PM on Sept. 19, 2017, the night before Maria made landfall, employees finished up a tableting operation. Two other manufacturing lines were operational during the storm, with one batch wrapping up the morning the hurricane blew in.

Puerto Rico’s bioscience industry by the numbers

▸ 3.3 million: Population of Puerto Rico

▸ 38,000: Number of bioscience employees on the island

▸ 2%: Proportion of total U.S. biopharmaceutical employees who are located in Puerto Rico

▸ 30%: Proportion of Puerto Rico’s GDP that came from biosciences in 2016

▸ 5: Number of the world’s top 10 selling biologic drugs manufactured in Puerto Rico

▸ 11: Number of world’s top 20 pharmaceutical products manufactured in Puerto Rico

That those lines were still running wasn’t some act of corporate heroism. Amgen, like a handful of other drug manufacturers on the island, had little choice but to maintain those complex and delicate lines: They harbor vats of microbial cells that churn out critical antibody drugs, like the anemia treatment Epogen. The cells need food and energy to survive and have very specific preferences about the temperature of their bath. Living factories don’t just pause their work at the whim of Mother Nature.

Losing those lines could have cost the company millions. But there were also bigger stakes to consider: With 50-odd pharmaceutical manufacturing sites squeezed onto a landmass the size of Connecticut, Puerto Rico is a critical component of the global drug supply chain. On a dollar basis, people in the U.S. take more drugs made in Puerto Rico than from any other state or country. Some medicines are made only there. If plants like the one in Juncos went down, the effect would be felt around the world.

The local impact would also be enormous. The industry is a vital part of the Puerto Rican economy—a major source of both employment and revenue.

What would unfold in the next hours, days, and months would all be in the service of maintaining that steady flow of pharmaceuticals. During that time, the industry was kept afloat by a symbiotic relationship between companies and their staff. Companies provided significant support, turning their sites into oases for employees whose lives outside work felt overwhelming and chaotic; employees displayed a tenacity and loyalty that allowed a critical segment of our global pharmaceutical supply chain to be maintained, despite significant challenges. Achieving that balance required a gargantuan effort and cost.

A year later, site leaders from major drug firms have done much reflecting on how their teams pulled together during an incredible catastrophe on the island. They’ve spent many months swapping lessons learned from situations no one predicted and have outlined changes being made to try to mitigate some of the most critical issues to emerge after the storm. Above all, they acknowledge that without their employees’ incredible resiliency—a word repeated time and again in interviews with C&EN—the following story would be much different.

Weathering the storm

Around 6 AM on Wednesday, Sept. 20, 2017, Maria’s eye hit Puerto Rico’s southeastern shore, passing just shy of the small city of Yabucoa before grinding diagonally across the island. By 8 AM, it had moved—along with its 250-km/hour winds—near Caguas, hovering due east of Juncos.

Strong winds and searing rain had arrived long before then. The predawn hours at Juncos were punctuated by minor emergencies, recalls Kerry Ingalls, vice president of site operations for Amgen Manufacturing, who runs the site. Like every big company, Amgen has a detailed business continuity plan meant to provide guidance for the minutiae of every disaster. But, as Ingalls puts it plainly, “Crises don’t follow the script. Weird things happen.”

Scenes from Amgen’s Juncos site

Like, for example, when fire alarms start ringing simultaneously in three separate buildings. It happened at 6 AM, at the height of the storm, and Ingalls was able to quickly assess that two were false alarms. But the third, in AML1, the oldest building on-site, appeared real. Using cameras to search around the building, the team could see that the roof had partially collapsed, triggering a water-flow alarm in the process. The lack of a fire was a relief, but nothing could be done about the damage.

Meanwhile, the waterproof seal protecting the administrative building where most staff had congregated began to leak, so even those huddled in a conference room on the third floor had to slosh around. Between that and flooding elsewhere in the building, employees scrambled to divert water to the cafeteria, sacrificing it to preserve offices and other essentials on the first floor.

By 2 PM, Ingalls felt confident enough to go out in a security truck and get a first assessment of the damage. Maria was by then making an exit at the northern border of the island. Debris was everywhere, some trees were flattened, and water had seeped into buildings across the campus, but Ingalls was pleased to find that, aside from the one roof, buildings had held up well.

In the distance, El Yunque was almost unrecognizable. The storm had denuded the trees, turning the typically verdant landscape into a splotch of brown.

As Maria made its way toward the mainland U.S., Puerto Rico was coming to terms with the magnitude of the disaster. Flooding, mudslides, and flying debris had destroyed tens of thousands of houses and blocked roads across the island.

The challenges were magnified by the double-whammy loss of power and loss of communication systems. People were cut off from help at the time they needed it most. Beyond the lives lost as a direct cause of the hurricane’s force, recent assessments conclude that thousands more perished in the days and months after the storm.

As crisis management teams at Amgen and other pharma sites across the island began to take stock of the damage, they balanced a number of priorities: making sure all their employees were safe and assessing their needs while coming up with a plan that would allow sites to get back up and running as quickly as possible.

Among their first tasks was to track down employees—thousands of them. Some lived in areas made impassable by downed trees and light posts or a fallen bridge. The gravity of the situation was difficult for those outside Puerto Rico to grasp. Ingalls would phone into headquarters by satellite phone and mention that he was working hard to account for all his employees, “and they’d say, ‘Well, why don’t you just post something to Facebook?’ ” he recalls with equal measures of amusement and exasperation.

It took Amgen nearly a month to find everyone. Many companies, like Johnson & Johnson, which took 23 days to account for its roughly 3,700 people who work at six plants across five municipalities on the island, began going door to door to find the last employees on its list.

Some were easy to find; they showed up at the gates a few days after the storm, ready to work. Amgen, like every other pharma firm, had broadcast messages on multiple radio stations to let employees know that only essential staff would be needed. But on Monday morning, when José Vidal, at the time the vice president of drug substance operations at Amgen, made his way to Juncos, he found hundreds of employees lined up, ready to work.

Similar scenes were unfolding at drug sites across the island.

The lines of workers also drove home the desperation to return to normal life. Although the Juncos site had enough backup power to be fully operational—and one microbial production line continued running for several days after the storm—it was nowhere near ready to spring back into the everyday routine.

“That’s when it got really emotionally bad for us,” Vidal recalls. “Seeing your colleagues—your friends, right?—who are day in and out with you, and they had no food or gas, and you had to tell them, ‘You have to go back home.’ That was just heartbreaking.”

Home to some 50 pharmaceutical manufacturing sites, Puerto Rico is a key component of the global pharmaceutical manufacturing chain.

1 Juncos: Amgen's Juncos site is the largest in its manufacturing network, with roughly 2,700 people working across its five plants to produce 13 of the company's drugs.

2 Las Piedras: Merck & Co., which employs roughly 600 people on the island, shipped over a 1,500-kW generator from its West Point, Pa., site to support operations in Las Piedras.

3 Jayuya: Many employees living near Abbvie's site in Jayuya were still without power 11 months after the hurricane.

4 Barceloneta: Abbvie's Barceloneta site benefited from a cogeneration plant, which allowed it to power another company and the local bakery after the storm.

5 Vega Baja Pfizer's Vega Baja site, one of three that collectively employ about 1,900 people plus contractors, packed its first batch of medicines on Nov. 2nd, about six weeks after the storm.

6 Guaynabo J&J's Guaynabo site, home to corporate and commercial functions, is part of a broad network on the island, with some 3,700 employees working across six manufacturing sites.

7 Carolina Eli Lilly & Co. is one of six companies to manufacture biologic products, like the insulin made at its Carolina site.

A new normal

One of the big lessons that pharma site leaders learned in the aftermath of Maria was that “aside from the buildings and products, the first thing we needed to manage was establishing society,” Vidal says. “Everything was chaos, so we needed to establish order within the confines of Juncos. There was a bubble where you should feel normal, you should follow some rules, you have shelter.”

Carlos Martis, site leader at AbbVie’s Jayuya site, recalls everyone’s shock when, just days after the storm, an employee who had lost her dad in a landslide appeared at the gate. The funeral home wasn’t open yet, and until then, she told Martis, “I just need to work. I need to reestablish my world,” he recalls.

The first step of reestablishing order was to mitigate, as much as possible, the humanitarian crisis unfolding across the island. Site leaders, coordinating with crisis teams at headquarters on the mainland, worked to quickly assess and, where possible, address the needs of their staff. But with relief personnel and aid rightfully taking priority at the airport and ports, getting supplies in—and, later, pharmaceutical products out—was a logistical nightmare.

Before the storm, J&J had set aside supplies at a warehouse in Jacksonville, Fla., just in case. The company managed to pack them onto a flight that reached San Juan two days after the storm.

When the truck carrying pallets of water and other relief items pulled into the loading dock of the company’s Guaynabo site at 3 AM on Friday, executives—and their families, who had been hunkered down with them—were reinvigorated.

“The level of satisfaction when we saw that truck—that made a whole difference in the world,” Ernesto Lugo, global senior director for risk and crisis management at J&J, says with a wide smile. That shipment would be the first of 27 flights and 20 ocean containers carrying emergency supplies sent by J&J.

By the third week, Amgen had set up “Camp Phoenix,” an ad hoc assembly of temporary shelters and tents to distribute aid. The amenities offered went far beyond just the basics of potable water and food. Dozens of washers and dryers were set up, and employees could drop off two bags of clothes per week. Staff could take a hot shower—a true luxury—or eat a hot meal. Amgen also brought in ice makers, and employees took home bag after bag to help keep food, and more critically, medicines, from going bad. A gas station set up on the north end of the site saved employees from queuing for hours to fill up their tanks to get to and from work.

Advertisement

“We decided we were going to make this site an oasis for the staff where we help give them the tools to not only take care of their families but to help us get the site back. To enable both, really,” Ingalls says. He jokes that the site had everything but a barbershop, an amenity the former Navy captain continues to be perplexed was left out, “because I love getting haircuts.”

That concept was repeated at pharma sites across the island. As more employees began returning to work, childcare was set up to account for the many schools and day-care facilities that were knocked out of commission. Collectively, companies shipped thousands of generators and gas stoves for employees from the mainland at a time when it was otherwise impossible to track one down on the island.

They provided such basic services for months. While some people got power back within six weeks, many more living in the communities surrounding these big drug manufacturing sites went without for months. In early August, nearly a year after Maria, a substantial number of workers at AbbVie’s site in Jayuya, a small town that sits at the highest point on the island, still had no electricity.

“Many people talked about how being here at work was not the reality—it was a luxury at the time,” says David Thompson, general manager at AbbVie’s Barceloneta site. “We had air-conditioning, we had communication, we had running water, hot food. And you can work. When people left to go back home, it was a different life.”

The vulnerable points

Creating a safe space for employees was a crucial element to restoring drug manufacturing to normal levels, pharma site leaders readily admit. Executives were keenly aware of the need to get operations back up and running as quickly and with as much stability as possible, for the benefit of global drug supplies as well as Puerto Rico.

Of the top 20 medicines sold worldwide, components of 11 are manufactured on the island. The drug supply chain has some flexibility—companies can shift manufacturing to sites in other countries, for example—but the portion of the pipeline potentially affected by Maria risked bottom lines as well as the overall pharmaceutical supply chain.

The stakes were high for Puerto Rico itself too: As of 2016, the drug and devices industry represented nearly 30% of its overall gross domestic product, and some 38,000 people worked in the biosciences.

As media began to report the outages at plants on the island, and U.S. Food & Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb issued statements on the issue, worries over drug shortages heightened.

Even as sites began to feel more stable than the outside world, executives knew that order was fragile. Site leaders took extreme measures to keep things on track. For example, Amgen’s four senior vice presidents, which included Vidal and Ingalls, took on 24-to-48-hour shifts to ensure that someone would always be at the site in case of an emergency. “It proved to be a very helpful and wise decision because every night after the hurricane, for the next four or five weeks, something happened,” inevitably at 2 or 3 AM, Vidal notes wryly.

That routine lasted about 40 days. Vidal was a lucky one: His office carpeting had remained dry even at the height of the storm, so he had a reasonable place to sleep. Ingalls took to crashing on the large U-shaped table in the main conference room. At first, he was avoiding the wet floor, but colleagues say he stuck to that spot even after the carpeting had aired out—the former Navy officer’s time on submarines must have conditioned him for uncomfortable situations.

During that frenetic period, site managers had to close gaps in companies’ seemingly meticulous business continuity plans. Among the issues laid bare by the storm was the widespread assumption that communications and operations would continue so long as power was on. Everyone planned for plants to run according to paper versions of the standard operating procedures.

Amgen’s Juncos site, however, didn’t have printed versions on hand, and flooding of the site’s main computer control room severed its connection to servers in California. The makeshift solution was for a team at the company’s headquarters in Thousand Oaks, Calif., to print out the paperwork and fly it over to the island. “These guys spent 48 hours in rotations continuously printing documents,” says Vidal, who happened to be in Thousand Oaks when Maria hit. When he and colleagues from Juncos returned to San Juan four days after the storm on Amgen’s corporate jet, they took along a half-dozen boxes of documents.

Lack of internet access also meant that inventory couldn’t be tracked. “Not having that connectivity to systems kind of prevented operations from starting up,” J&J’s Lugo says.

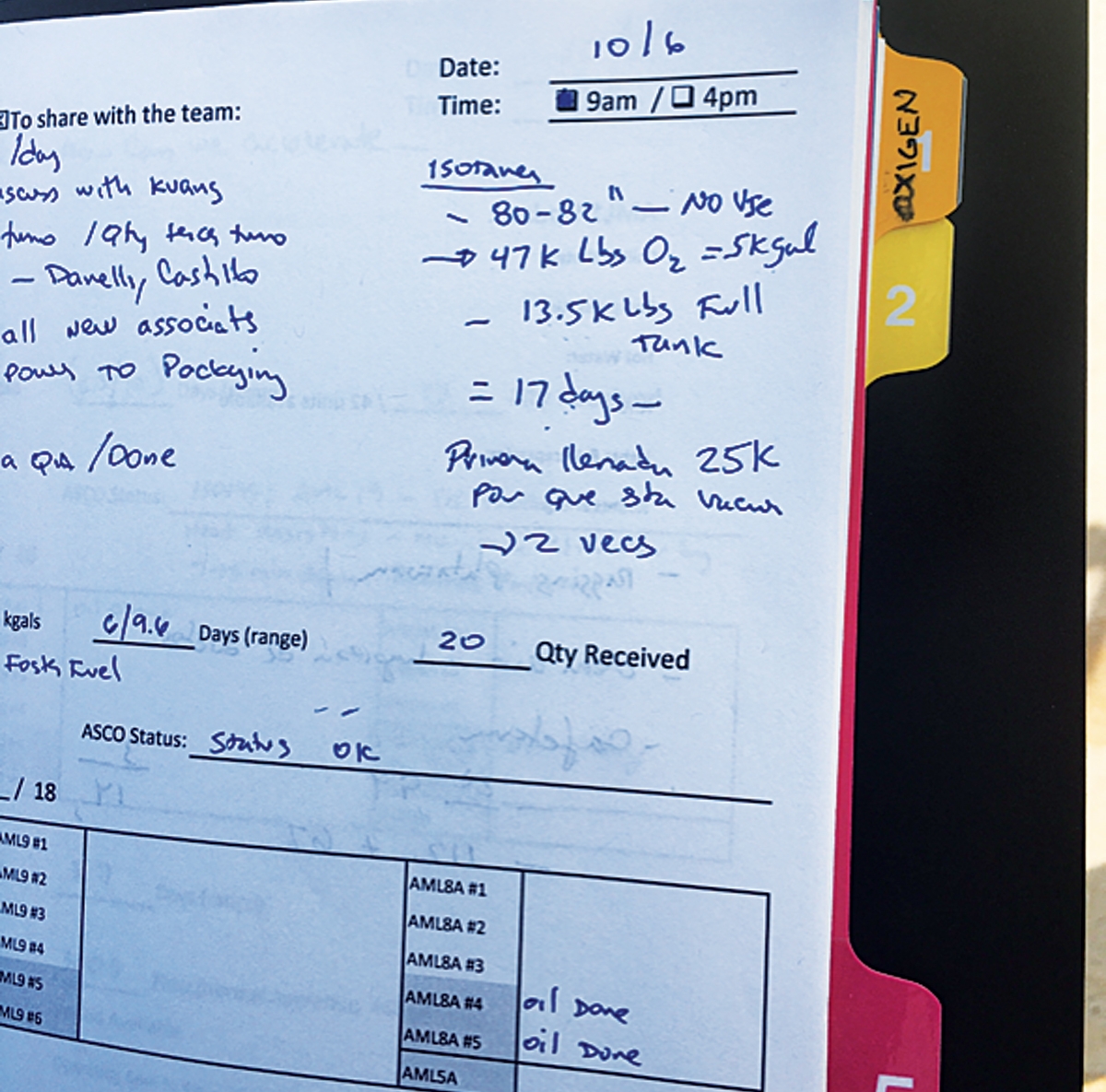

Perhaps the most critical situation in Juncos and for several other biologics manufacturing sites across the island was a shortage of high-purity gases. Site leaders found themselves in a real bind. Those delicate cell lines need oxygen and nitrogen to survive. “Without oxygen, you’re dead in the water—no product, and millions of dollars in waste,” Vidal says. The storm put companies’ suppliers out of commission, and any oxygen that made its way to the port was diverted to hospitals.

The situation reportedly became so dire that according to sources, one company risked losing $200 million in material as it got down to its last two days of oxygen.

In that moment, the island’s size—just 160 by 56 km, as everyone is quick to tell visitors—began to work in its favor. The life sciences community is exceptionally tight, and soon, Amgen executives found themselves working with their counterparts at AbbVie and Becton, Dickinson & Co. to share their dwindling supplies and source gases.

“We ended up having to work externally to bring material in from Europe and the U.S.,” AbbVie’s Thompson says. He adds that although they were competitors, “work between companies was tremendous and, I think, unique to Puerto Rico.”

Lessons learned

The first thing any drug company executive sitting down to discuss Maria and its aftermath will say is, “This was a 100-year event.” The last time the island witnessed a storm anywhere close to this magnitude was Hurricane Georges, a Category 3 storm that struck in 1998. Although well versed in the statistics, the executives concede that a changing climate could bring more Marias more often. The question is whether drug companies can ever prepare enough to mitigate the next big storm—and avoid potentially disastrous drug shortages.

The question is fair, but it should be broadened beyond Puerto Rico or even hurricanes more generally, says James Bruno, president of the consulting firm Chemical & Pharmaceutical Solutions. “You can’t really schedule” a natural disaster, and they come in all shapes and forms, he says. For example, when Eyjafjallajökull erupted in Iceland in 2010, the weeks-long disruption to air travel reverberated across the pharmaceutical industry. Companies had to scramble to ship drugs from Ireland, one of the other critical manufacturing hubs, to ports in France and the Mediterranean for global distribution.

“The cost of eliminating the risk is going to be so astronomical, none of us could afford it,” he says. “We’d have to put up superstructures that can defy anything—volcanoes, earthquakes.”

Moreover, no two disasters unfold in the same way, making it impossible to fully predict and prepare for every possible scenario. Even for Puerto Rico, “If a hurricane were to come through again, I can’t tell you that the island or the site would be exactly the same, you know, two hours after the storm’s gone,” Ingalls says.

That’s not to say that in the wake of Maria, drug companies have maintained the status quo. Manufacturers identified several key areas where improvements have already been made or are being planned.

The two biggest changes to big pharma firms’ planning for this and future disasters are in developing more robust communications and power systems. No one expected communications to be down at all, let alone for months. “We had some satellite phones that sometimes worked, that sometimes didn’t, depending on if it was too cloudy or if there were interruptions or blockages,” J&J’s Lugo says. “It was a struggle.”

J&J has since revised its basic telecommunications requirements for each facility and is creating backups for the backups. In addition to satellite phones, sites now have high-frequency radios, microwave technology, and satellite dishes. “In case something like this ever happens again, at least we have some better tools to communicate,” Lugo says.

Other companies are responding similarly. “The majority of the changes we have made to business-continuity plans for readiness, during an event, and recovery were based on ‘What if we don’t have communication channels?’ ” says Lourdes Colón, vice president of operations at Eli Lilly & Co.’s manufacturing site in Carolina, P.R.

AbbVie’s communications upgrades mirror those at J&J, and the company is also working on developing a concept it calls “plant in a box.” “We either have local servers or images on our local servers of everything that is necessary to be able to run our quality systems, our maintenance system, our production system within the plant without connectivity” beyond the site, Thompson says.

Sites have additionally bolstered backup power systems. Everyone had backup generators, but no one anticipated the strain put on them. When Hurricane Irma arrived two weeks before Maria, Amgen’s Juncos site ran on diesel generators for nearly a week. “It set a new site record—six straight days,” Ingalls says. “And then comes Maria, and we were on diesels for over 120 days straight with no interruptions in site operations due to power.”

“I’m not talking about just keeping the warehouse cold,” Ingalls emphasizes. “I’m talking about everybody at work, all factories operating at full production on diesel power.” Amgen has since invested $40 million in a cogeneration (cogen) plant, an efficient system that provides both heat and power, that is expected to be operational later this year.

Pfizer has also added more generators and is investing in a cogeneration unit at its Vega Baja site. The additions will give it full redundancy, says Sigfrido García, the facility’s director of competitiveness, technology, and business development.

AbbVie’s Barceloneta site was one of the few that already had a cogen unit, which allowed it after the storm to power not just its own operations but also an adjacent manufacturer and a local bakery. But AbbVie is now installing two more cogen units plus other backup generators at its sites. “We have the redundancy of the redundancy,” Martis says with a grin.

Companies are also working with the Puerto Rican government in hopes of improving the coordination of relief efforts during future events. Executives note that, unlike during Maria, the government has now established a central location, a Sheraton hotel in San Juan, to house agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Department of Homeland Security. That will give companies an immediate one-stop shop for help.

Meanwhile, they are also pushing the government to have a better plan for bringing in aid as well as the supplies needed for businesses to run as usual. After Maria, “the backlog of containers at the port was huge and lasted weeks, if not months,” says Rafael Castro, vice president of operations for the Pharmaceutical Industry Association of Puerto Rico. That traffic jam “really hindered both the emergency rescue operations and the recovery operations.” One possible solution under discussion is to maintain regular goods at the port in San Juan and shift emergency supplies to another port, possibly in Ponce or Mayagüez.

Another area that companies are addressing is contingency plans for external suppliers. Big companies themselves might have managed to create an oasis after the storm, but the situation for critical suppliers—the medical gas companies, for example—was more dire.

“We’ve looked hard into changing some of our business-continuity approaches to take into account the fact that we are on an island,” Amgen’s Ingalls says. “Maybe the backup needs to come from off the island, not somewhere else on the island.” After all, “it doesn’t matter how many backups you have if everyone’s affected by the same crisis.”

Bruno of Chemical & Pharmaceutical Solutions agrees that companies should be taking a closer look across their entire supply chain and adjusting their business contingency plans. The smaller cogs in the elaborate pharmaceutical manufacturing machinery could mean the difference between supply continuity or shortage. “I don’t think people realize how vulnerable we are in the United States for drug shortages,” Bruno says.

Even as pharmaceutical site managers who led their teams through Maria and its aftermath acknowledge planning weaknesses, they fiercely defend their sector’s strengths. The pharmaceutical supply chain did not grind to a halt. They point out that aside from one manufacturer that had preexisting issues, the global flow of drugs or devices was steady. Companies were back to running some or all parts of their facilities on average within two weeks, a statistic everyone is quick to cite.

That was due in part to strict manufacturing requirements by FDA. “We complain every year about all these inspections and how tough they are, but it paid back for us,” Amgen’s Vidal says, adding that companies “were in such a state of compliance” that the right procedures were in place to bounce back after the hurricane.

Nearly a year out and fully immersed in yet another hurricane season, employees are still emotional when talking about the events and lessons of Maria. They say they are personally better prepared this time around—everyone has their generator tucked away and plenty of supplies on hand just in case. At least while the memory is fresh, no one is going to underestimate another storm.

And at Amgen, employees are hoping for a more formal memorial. The roof that collapsed and set off a fire alarm at the height of the storm had sheltered one of the site’s original buildings. That exposed area has been razed, leaving the concrete foundation as a large, bare rectangle that employees call Maria Plaza. They hope it will be turned into a lasting tribute to what they endured, together.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter