Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biosimilars

New federal rules are supposed to make biosimilars more accessible. Will they work?

The FDA's new guidance defines interchangeability and will use insulin as a test case

by Megha Satyanarayana

June 3, 2019

In a long-awaited move, the US Food and Drug Administration has released a set of guidelines intended to stoke the market for biosimilars, generic versions of complex biological drugs, frequently proteins, that are used to treat diseases like cancer and autoimmunity.

The FDA has already approved 19 biosimilars. However, none of those drugs can be substituted—or interchanged by a pharmacist—for the reference biological drug from which they are derived. The new guidelines set testing standards for a biosimilar to be declared interchangeable, allowing pharmacists to replace a branded drug with a generic biologic in the same way they currently do for small-molecule drugs, without having to talk with a doctor first.

Both patient advocates and the FDA hope that bringing more biosimilars to market will improve access to these groundbreaking drugs by giving consumers more choices and by lowering prices. In one study of patient costs for biologics to treat autoimmune disorders, annual out-of-pocket costs ranged from $22,000 to $29,000. The wholesale prices of the biologics examined in the study ranged from about $700 to more than $7,000 per dose.

The FDA plans to use insulin as a test case of the new guidance. Generics versions are rare in the US, and increasing costs of the drug in recent years have led to reports of people with diabetes rationing supplies or skipping doses.

But not everyone is convinced the new guidance will make a big difference for consumers. The rules appear to apply to only a narrow subset of biologics that can be sold through a pharmacy directly to consumers rather than treatments that are given by a doctor through infusion or injection. Development costs for biologics are high. New interchangeable biosimilars might get stuck in patent litigation, which has been the fate of many biosimilars already approved. And in Europe, where more biosimilars are used, prices haven’t dropped as drastically as some people anticipated.

“Anything the FDA can do to encourage competition in this space is very useful to the consumer,” says Michael Carrier, a professor at Rutgers Law School who specializes in pharmaceutical patent law. “As helpful as it is, though, there are still many hurdles to biosimilar competition,” he warns.

One of those hurdles for a biosimilar maker is in recreating the manufacturing process of a reference biologic. Unlike the fairly straightforward steps required to synthesize a small-molecule drug, biologics are typically made in living cells.. Cell culture conditions have to be just right to create a properly folded therapeutic in good quantity. Biologic proteins may need chemical modifications to function properly in humans. These modifications can include the addition of carbohydrate groups or the removal of amino acids to make a protein more soluble. And all this must be scaled up for manufacturing.

Meeting these challenges has already proved to slow the introduction of some biosimilars to the market. FDA approval of Celltrion’s biosimilars of cancer treatments Rituxan and Herceptin has been held up because of manufacturing issues.

And then there are the testing requirements.

To be fully interchangeable, per the FDA guidance, a company developing a biosimilar that it wants to be interchangeable might have to perform pharmacological tests to show how the body uses and metabolizes the protein and that providers can switch between drugs for the same illness without any safety and efficacy issues; the company may also need immunological tests to show that the protein isn’t inadvertently setting off the body’s defenses.

For some candidate biosimilars, this testing might be a bit like reinventing the wheel, says Gillian Woollett, an industry analyst at Avalere Health. In Europe, where dozens of biosimilars have been approved and are in use, and many are assumed to be interchangeable with their reference drugs.

In addition, US and European doctors also switch patients between different brand-name biologics with similar modes of action to treat the same disease. For example, several brand-name biologics attack the tumor necrosis factor pathway to thwart the inflammation seen in diseases like psoriatic arthritis. Evidence from Europe, she says, shows that such substitutions have little cause for concern.

“The FDA knows the science better than anyone,” Woollett says about the process of making and testing biologics and biosimilars. Information from Europe and from doctors who prescribe biologics should be enough to show that a biosimilar would probably be just as good as the reference therapeutic; the FDA’s new guidance does not represent a higher standard, Woollett argues. The testing “is just additional data on a product that is already biosimilar. So you’re not polishing and making it better—it’s exactly the same product.”

Overall, it takes more time and money to reproduce a biologic than it does a small molecule, according to a report from the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

“A biosimilar manufacturer must recoup its development costs, which are much higher” than for small-molecule generics, Carrier says.

As for the FDA’s test case for its interchangeability rules, a quirk of history means that insulin—a peptide hormone made of 51 amino acids—is not currently considered a biologic, but a small molecule. The FDA must first reclassify the drug, which FDA acting Commissioner Ned Sharpless says will happen in March 2020.

At a recent hearing, Sharpless said the guidance should affect the market for and availability of insulin, the cost of which has skyrocketed. He said that the maker of one insulin formulation has raised the price of the drug some 600% from 2012 to 2016.

“As a physician, I find this intolerable. No patient should have to choose between paying for medicine and paying for their rent,” Sharpless said.

Abhijit Barve, head of global clinical research at Mylan, noted during the hearing that Mylan’s biosimilar insulin glargine is already available in Europe. Insulin is more like a small molecule than a complex biologic, he said, and researchers already know a lot about how insulin behaves in the body. Barve conceded that there could be questions about biosimilar insulin’s effect on the immune system, but he emphasized that requiring a bunch of additional testing “would only be a barrier to development.”

Even if more biosimilars make it to market and become broadly used, prices might not drop that much. The biosimilar version of Janssen’s Remicade for chronic inflammation is only 15% cheaper than the branded product, according to the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes report. The researchers predict that, as in Europe, US prices for biosimilars won’t go much lower than 30% below the brand-name therapeutic. But brand-name-biologics manufacturers are already testing that prediction, at least in the case of insulin. Eli LIlly and Company recently undercut itself, releasing a generic version of Humalog, its multibillion-dollar-per-year insulin, at half the price.

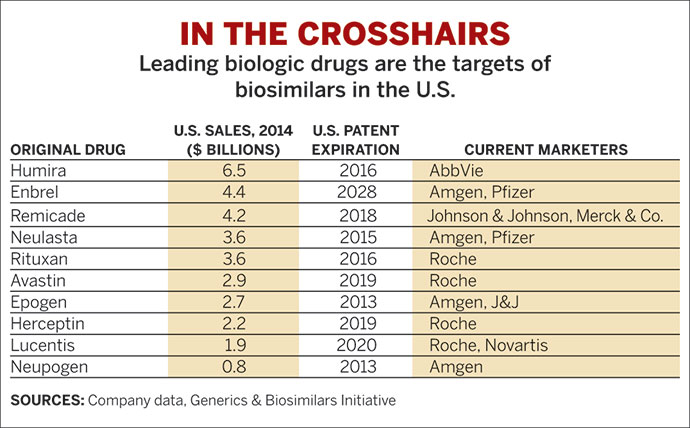

And another challenge to making biosimilars broadly accessible is patent protection. Of the 19 FDA-approved biosimilars, not all are on the market. Some are tied up in patent and other litigation, Rutgers’s Carrier says, noting that AbbVie, the maker of the industry’s top-selling biologic, Humira, has more than 130 patents on nearly every aspect of making the antibody. As part of a settlement with AbbVie, companies creating generics of the drug have agreed to stay out of the US market until 2023.

But the US market is key, Woollett says. About 60% of biologics spending happens in the US. The availability of biosimilars worldwide hinges on success in the US market.

“If we fail in the US when we are the single biggest market in the world, we have to ask whether this impacts the ability of the rest of the world to have economically viable biosimilars either,” she says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter