Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Discovery

Fentanyl antibody to begin clinical trials

Researchers hope to show that immunotherapies can fight the opioid crisis

by Laurel Oldach

August 7, 2023

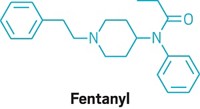

The concept of using immunotherapy to treat opioid addiction will soon see its first test in humans. An antibody that binds to fentanyl, reported recently in ACS Chem. Neurosci. (2023, DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00455), is also scheduled to start clinical trials later this month. The developers think the molecule might help treat people with addiction or even reverse overdoses.

Naloxone (Narcan), the only available treatment to reverse an overdose, blocks the receptor that fentanyl and other opioids activate. However, its half-life is shorter than that of many opioids; if it wears off, a patient can slip back into overdose.

Some researchers have worked for years on antibodies to block drugs of abuse from reaching the brain. The opioid crisis—especially the emergence of fentanyl and its analogs which are involved in the majority of overdose deaths today—has revitalized interest.

Researchers led by Kim Janda at Scripps Research Institute generated an antibody that binds to fentanyl and the more-potent analog carfentanil, but does not interfere with naloxone. In contrast to prior antibodies the lab had generated, this molecule has a fully human amino acid sequence, a plus for drug development. The researchers also engineered a stable antibody fragment.

Cessation Therapeutics has licensed and is developing both proteins, and will soon start a Phase I clinical trial with the larger molecule. The company is exploring ways to use the antibody alongside methadone or suboxone as a monthly combination therapy for cravings.

Janda is more excited about the fragment, which his lab showed could restore breathing in mice overdosed with carfentanil. He says it could be delivered into muscles with an EpiPen-like injector, potentially offering an overdose reversal that would kick in more slowly than Narcan but last longer.

Marco Pravetoni, whose lab at the University of Washington is developing different opioid antibodies and vaccines, says that this molecule may prove that immune approaches would work for opioids.

However, according to overdose prevention project coordinator Alice Bell of Prevention Point Pittsburgh, repeated doses of Narcan are adequate for most overdoses—if only people could obtain it. “People die because they are alone, because they don’t have naloxone and because they don’t know how much fentanyl is in the drugs they buy,” she says in an email. “New, more expensive agonists are not the answer to the problem.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter