Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Chemical Weapons

Tear gas and pepper spray: What protesters need to know

Experts discuss the use and chemistry of the riot-control agents and how to neutralize their effects

by Craig Bettenhausen

June 18, 2020

“I remember dropping to my knees and just coughing, just trying to get air in,” Emanuel Waddell says. “You can’t breathe.”

That’s how Waddell, a professor of chemistry at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, describes being exposed to tear gas nearly 3 decades ago. At the time, he was in graduate school at Clark Atlanta University during the 1992 protests over Rodney King’s beating by Los Angeles police officers.

A protest march passed by the building where Waddell was working, and he went to see what was happening. Tear gas drifted into the building, and it was all-consuming. “It was a horrible, horrible feeling,” says Waddell, who is also a former president of the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE). “It’d be like taking peppers and rubbing them in your eyes.”

Twenty-eight years later, law enforcement agencies around the world still deploy tear gas and other chemical irritants to control crowds. In the US, clouds of tear gas billowing from canisters and pepper spray drenching the faces of demonstrators have become some of the defining images of 2020, as protesters gather to call for justice for George Floyd and an end to police brutality against Black people.

Because of the ubiquitous use of riot-control agents during such protests, demonstrators want to know what they’re being exposed to and how they can neutralize the chemicals’ effects. As Waddell’s experience shows, being peaceful or even uninvolved doesn’t always mean a person won’t be affected.

Riot-control agents like tear gas and pepper spray are banned from use in warfare under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). Yet they may still be used for law enforcement and riot control, explains chemical weapons specialist Marc-Michael Blum, founder of Blum Scientific Services, which focuses on analytical testing and training in the areas of chemical and biological defense.

The CWC and local regulations stipulate that certain chemical agents may only be used for riot control when officers give people adequate warning before releasing the agents and people have a reasonable route to escape any gas. Neither of those conditions makes sense in a battlefield setting, which is one of the reasons tear gas and pepper spray are banned in warfare, Blum says. He adds that the ban in warfare helps prevent conflation of riot-control agents with more deadly chemical weapons.

US Attorney General William Barr said recently that the use of pepper spray and tear gas in the US has been appropriate during the 2020 protests because law enforcement officers have “met resistance.” Law enforcement advocates such as police unions hold up nonlethal weapons such as chemical agents and rubber bullets as important, “medium-force” options for controlling crowds when verbal commands aren’t working and lethal force isn’t warranted.

Without any medical attention, the effects of pepper spray and tear gas tend to wear off within 30 min, Blum says, although pepper spray stimulates lung inflammation that can be dangerous for people with existing breathing problems. Reviews of the substances’ toxicity by Sandia National Laboratories and Virginia Commonwealth University report that long-term effects are rare.

The chemical nature of riot-control agents came into sharp focus in the US in early June after federal forces cleared protesters from the streets and sidewalks north of Lafayette Square, in front of the White House. President Donald J. Trump walked through the area to pose for photos and videos in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church, which had been the site of a small fire the night before. A week later, a CBS reporter asked Barr about the federal agents’ use of chemical agents to clear the square that day. Barr claimed that no tear gas was used, referring only to the use of pepper balls. “No, there were not chemical irritants; pepper spray is not a chemical irritant. It’s not chemical,” he told CBS.

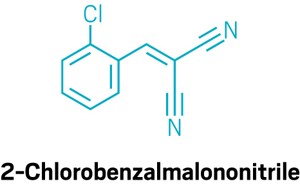

Local CBS reporters on the scene of the incident recovered still-warm spent canisters labeled Spede-Heat CS, as well as canisters labeled Skat Shell OC. CS is 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile, a common type of tear gas, and OC stands for oleoresin capsicum, the active ingredient in pepper spray. CS has mostly replaced an older tear gas chemical, known as CN for chloroacetophenone, because CS is less toxic and more potent.

“I was coughing with tear gas in my clergy collar, and my gray hair, and my old lady reading glasses,” Gini Gerbasi told a Washington, DC, CBS station. Gerbasi is a priest from a nearby Episcopal parish who was on site at St. John’s handing out medical supplies with Black Lives Matter activists.

“When they say it’s not chemical,” Waddell says, “it’s definitely chemical.”

Pepper balls are similar to paint balls, except that instead of paint, they contain fine-powdered CS, OC, or other chemical irritants, according to the company PepperBall, which holds a suite of patents on the technology. Upon impact, pepper balls burst and release their contents in a large dust cloud.

Tear gas doesn’t have a rigid definition, according to chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta, who is managing director of the consulting firm Strongpoint Security. Tear gas is a slang term that usually means CS in the law enforcement world but can also include OC and other chemicals.

OC is an oily extract from hot pepper plants. Weapons makers emulsify it in water and propylene glycol or dissolve it in organic solvents to make aerosol pepper spray. They may also compound it into a powder. OC extract is mostly composed of capsaicin, the same compound that gives spicy food its hotness. Sriracha, a popular type of hot sauce, lands between 1,000 and 2,500 on the Scoville scale, a measure of spiciness. OC pepper sprays, by contrast, clock in north of 2,000,000 on the same scale.

Exposure to OC “is basically as if your head is on fire, and you inhaled a hive of angry wasps,” says JK, a PhD biochemist who was hit in the face with pepper spray by Hong Kong police during a protest in December. Activists have been protesting what they view as the Chinese central government’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s semi-independent status. Another consequence of being exposed to OC is “you also will wind up intensely sweating during the whole experience,” says JK, who asked to be identified by only their initials for fear of retribution by the Chinese government.

The sweating is likely thanks to a human pain receptor called TRPV1. When pepper spray is inhaled or absorbed by mucous membranes in areas like the eyes or nose, capsaicin makes its way to nerve cells. TRPV1 is a cation channel on those nerve cells that activates in response to capsaicin and related molecules like allyl isothiocyanate, which gives mustard and wasabi their sting. Activating TRPV1 sets in motion a cascade of events that sends pain signals to the brain. TRPV1 is also heat-activated, so researchers suspect it’s involved in the body’s temperature regulation. Thus, the sweating.

CS is a synthetic molecule that is solid at room temperature. It and similar compounds activate a pain and heat receptor in the body, TRPA1, that is similar to TRPV1. CS boils at 310 °C, so canisters like the ones found near St. John’s use a flammable propellant and an ignition system like that found in flares or hand grenades. That’s an extra danger for this type of riot-control agent, Kaszeta says, because the canister and the smoke escaping it are hot enough to cause burns.

In addition, CS breaks down into various other compounds at high temperatures. So “you’re not just using CS, you’re using CS plus a weird unknown cocktail of mystery chemicals” with unclear toxicology, Kaszeta adds. “CS as a burning canister probably should be banned.”

Riot-control agents were originally developed to subdue enemy soldiers and rioting prisoners, so they were tested on healthy, working age men, Kaszeta says. They weren’t intended for a crowd of mixed-health protesters and definitely not for a populace in the grip of a viral respiratory pandemic.

So what should you do if you’re exposed to tear gas or pepper spray?

Get away from the area, and wash with copious amounts of water—especially your hands and face, Blum says. Kaszeta also recommends “flapping your arms like a chicken” to shake off loose particles and help evaporate volatile components. Water accelerates the breakdown of CS via hydrolysis to malononitrile and o-chlorobenzaldehyde. Alkaline water (pH 9) substantially accelerates that reaction, though JK cautions against using high-pH water on your eyes. Hong Kong protesters have used water saturated with baking soda, which creates a basic solution, to treat exposure to tear gas.

OC, on the other hand, doesn’t undergo hydrolysis. Still, water can soothe its effects, and soap can help wash the irritating compound away. Some protesters use milk or milk of magnesia to neutralize the riot-control agents on the scene, but little to no data supports those treatments as effective.

Kaszeta says that most of the effect of riot-control agents is psychological: “If you get a good lungful of CS, you feel like you can’t breathe, but you actually can.”

Washington, DC’s City Council passed a law on June 9 barring the city’s police force from using chemical irritants or rubber bullets to disperse peaceful protesters, and other cities are considering similar measures. But such legislation is unlikely to constrain federal and state forces such as those that led the charge to clear the area around Lafayette Square. And police in other areas are still using tear gas on protesters: for instance, officers deployed it during a demonstration in Richmond, Virginia, on June 15. In Hong Kong, JK says, “It’d be easier to state where pepper spray isn’t being used on a given day,” and points to heavy pepper spray use on June 12 in the Mong Kok shopping district.

Waddell says it’s painful to see the tactics he experienced in 1992 continue to be used on protesters. “Using tear gas and rubber bullets indicates that, no, you’re not free to disagree. You’re not free to protest,” he says. “It should be outlawed.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter