Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Energy Storage

Iwnetim Iwnetu Abate

This materials scientist engineers new electrode materials for energy applications

by Shi En Kim

May 19, 2023

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 101, Issue 16

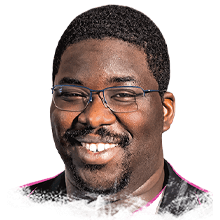

Credit: Greg Jansen/Rocket Headshots/Will Ludwig/C&EN | Iwnetim Iwnetu Abate

rowing up in a small town in Ethiopia, Iwnetim Iwnetu Abate didn’t have reliable access to power. For several nights a week, he completed his homework by the light of candles or a kerosene lamp. Abate’s experience eventually set him on a path to improve battery technologies. “I had this personal attachment to the problem of energy,” he says.

Abate—who goes by Tim in casual conversation—is now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His goal is to design high-performance materials that facilitate electrochemical reactions in batteries or offer improvements in catalysis, sensors, or computing. Throughout his research career, he has been driven to understand how atomic-level phenomena govern macroscopic behavior in layered materials.

“He’s very interested in seeing translation of his research to solve societal problems,” says Mark Asta, a computational materials scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, and former coadviser of Abate, who completed postdoctoral work as a Miller Fellow and President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at the institution. “He’s really driven to make a difference.”

Advertisement

At the heart of Abate’s materials design strategy is intercalation, the ebb and flow of ions in the surface layers of electrodes, where charge exchange and chemical reactions occur. His research scrutinizes the role and impact of these mobile charge carriers with the aim of harnessing their potential to modify their hosts’ properties. “This is a new, emergent direction,” says Will Chueh, a materials scientist at Stanford University and one of Abate’s former PhD advisers. “It’s a really powerful combination of the flexibility of electrochemistry and the interesting problems in condensed-matter physics.”

To navigate this new space, Abate wields both experimental and computational tools. While most researchers choose to specialize in one technique and collaborate with other researchers in counterpart areas, Abate has been pursuing both approaches simultaneously since his graduate school days, which gives him a holistic understanding of any scientific problem he’s dealing with, Chueh says. “He is extremely unique that he was able to put the two together.”

Abate’s proudest scientific achievement to date is applying both skills to untangle the decades-long mystery of why certain layered-oxide electrodes decline in performance after a cycle of charging and discharging. This deterioration means that batteries have to operate at half their theoretical energy density; otherwise they might fail because of material degradation and lose their rechargeability. Abate traced the cause of this problem to oxygen ions that like to pair up with each other, which may lead to structural collapses in the electrode. Armed with these atomic insights, Abate plans to develop design principles for circumventing this instability in electrode materials to boost overall battery capacity.

“I had this personal attachment to the problem of energy.”

—Iwnetim Iwnetu Abate, professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Although he’s working at the forefront of energy research, Abate recognizes that his lab’s contributions may not immediately impact many parts of the world, including his hometown, because of their lack of reliable access to power. Part of the reason for the low access, he says, is a dearth of educational opportunities to nurture the talent for engineering local solutions.

To tackle that problem, Abate and his colleagues have organized summer classes on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics subjects in Ethiopia almost every year since 2017. The volunteers also host webinars throughout the rest of the year. In 2020, Abate cofounded SciFro, a nonprofit organization that supports African youths in sciencing their way out of health- and energy-related problems in their communities—as Abate puts it, to “be creative with cheap resources.” The organization received funding from the National Science Foundation, the American Physical Society, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

How does Abate find the time to do it all? He credits his many scientific and outreach collaborators—“people with shared values and vision”—for allowing him to pursue his multiple passions in research as well as in life. But his peers also say that something about him draws collaborators to his cause. “He is inspirational,” Asta says. “You talk to the guy, and you say, ‘Man, this guy is going to change the world.’ ”

Vitals

Current affiliation:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Age: 30

PhD alma mater:

Stanford University

Hometown:

Debre Birhan, Ethiopia

If I were an element, I'd be:

“Gold. It passes through extreme conditions to be the valuable element it is. I believe adversity and challenges refine us the most to become the most valuable version of ourselves.”

My favorite movie is:

“The Pursuit of Happyness. The movie is inspirational for love, drive, and dedication—three of the characteristics I admire the most in people.”

Learn more/nominate a rising early-career chemist to be one of C&EN's Talented 12 at:

cenm.ag/t12-nominations-2024

Growing up in a small town in Ethiopia, Iwnetim Iwnetu Abate didn’t have reliable access to power. For several nights a week, he completed his homework by the light of candles or a kerosene lamp. Abate’s experience eventually set him on a path to improve battery technologies. “I had this personal attachment to the problem of energy,” he says.

Vitals

▸ Current affiliation: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

▸ Age: 30

▸ PhD alma mater: Stanford University

▸ Hometown: Debre Birhan, Ethiopia

▸ If I were an element, I’d be: “Gold. It passes through extreme conditions to be the valuable element it is. I believe adversity and challenges refine us the most to become the most valuable version of ourselves.”

▸ My favorite movie is: “The Pursuit of Happyness. The movie is inspirational for love, drive, and dedication—three of the characteristics I admire the most in people.”

Abate—who goes by Tim in casual conversation—is now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His goal is to design high-performance materials that facilitate electrochemical reactions in batteries or offer improvements in catalysis, sensors, or computing. Throughout his research career, he has been driven to understand how atomic-level phenomena govern macroscopic behavior in layered materials.

“He’s very interested in seeing translation of his research to solve societal problems,” says Mark Asta, a computational materials scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, and former coadviser of Abate, who completed postdoctoral work as a Miller Fellow and President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at the institution. “He’s really driven to make a difference.”

At the heart of Abate’s materials design strategy is intercalation, the ebb and flow of ions in the surface layers of electrodes, where charge exchange and chemical reactions occur. His research scrutinizes the role and impact of these mobile charge carriers with the aim of harnessing their potential to modify their hosts’ properties. “This is a new, emergent direction,” says Will Chueh, a materials scientist at Stanford University and one of Abate’s former PhD advisers. “It’s a really powerful combination of the flexibility of electrochemistry and the interesting problems in condensed-matter physics.”

To navigate this new space, Abate wields both experimental and computational tools. While most researchers choose to specialize in one technique and collaborate with other researchers in counterpart areas, Abate has been pursuing both approaches simultaneously since his graduate school days, which gives him a holistic understanding of any scientific problem he’s dealing with, Chueh says. “He is extremely unique that he was able to put the two together.”

Abate’s proudest scientific achievement to date is applying both skills to untangle the decades-long mystery of why certain layered-oxide electrodes decline in performance after a cycle of charging and discharging. This deterioration means that batteries have to operate at half their theoretical energy density; otherwise they might fail because of material degradation and lose their rechargeability. Abate traced the cause of this problem to oxygen ions that like to pair up with each other, which may lead to structural collapses in the electrode. Armed with these atomic insights, Abate plans to develop design principles for circumventing this instability in electrode materials to boost overall battery capacity.

Although he’s working at the forefront of energy research, Abate recognizes that his lab’s contributions may not immediately impact many parts of the world, including his hometown, because of their lack of reliable access to power. Part of the reason for the low access, he says, is a dearth of educational opportunities to nurture the talent for engineering local solutions.

To tackle that problem, Abate and his colleagues have organized summer classes on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics subjects in Ethiopia almost every year since 2017. The volunteers also host webinars throughout the rest of the year. In 2020, Abate cofounded SciFro, a nonprofit organization that supports African youths in sciencing their way out of health- and energy-related problems in their communities—as Abate puts it, to “be creative with cheap resources.” The organization received funding from the National Science Foundation, the American Physical Society, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

How does Abate find the time to do it all? He credits his many scientific and outreach collaborators—“people with shared values and vision”—for allowing him to pursue his multiple passions in research as well as in life. But his peers also say that something about him draws collaborators to his cause. “He is inspirational,” Asta says. “You talk to the guy, and you say, ‘Man, this guy is going to change the world.’ ”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter