Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Petrochemicals

Instead of battling for survival in the trough, the petrochemical industry is enjoying the climb to the business-cycle peak

by ALEXANDER H. TULLO, C&EN NORTHEAST NEWS BUREAU

March 21, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 12

North American petrochemical producers are becoming reacquainted with a concept that in recent years was all too alien to them: profitability.

Given the severity of the business trough from 2001 to 2003--when producers were hit by excess capacity, weak demand, high costs, and lost international competitiveness--they might have forgotten what it was like to make money in North America. But the tightening balance of supply and demand is turning petrochemicals into a seller's market.

The industry is now climbing toward the peak in its notoriously extreme business cycle. And just as the last trough was one of the worst in the industry's history, this new peak may turn out to compare well to the 1988–89 peak that observers remember fondly.

The ethylene industry's biggest windfall last year was growth. According to Mark Eramo, vice president of olefins for the Houston-based consultancy Chemical Market Associates Inc. (CMAI), the U.S. ethylene market grew between 8 and 9% in 2004, and he expects strong growth to continue this year.

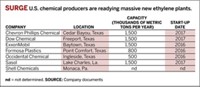

At the same time, the market's rate of capacity addition is low compared with the trough years, when several world-scale crackers came on-line in North America. The only new capacity in 2004 was a 1.1 billion-lb-per-year expansion at Shell Chemical's Deer Park, Texas, complex and 400 million lb from Huntsman's restart of its Port Neches, Texas, line. This year, only a 550 million-lb expansion at BP's Chocolate Bayou, Texas, complex is expected.

THESE ADDITIONS are offset by the roughly 4 billion lb of capacity that has been idled in the 55 billion-lb North American ethylene market since 2001. Some of the capacity--such as the 2.2 billion lb that Dow Chemical closed in Seadrift and Texas City, Texas--is shuttered for good.

Eramo says capacity reductions have been pivotal in helping to tighten the ethylene market. Effective operating rates--a utilization rate that excludes plants that are temporarily idle--have climbed from about 85% at the end of 2002 to more than 97% at the end of last year, according to CMAI.

The tightening market is driving up prices and margins. From December 2002 to December 2004, average ethylene prices nearly doubled to 41.5 cents per lb, according to CMAI. Meanwhile, ethylene cash profit margins--prices minus the costs of production--have increased from not much more than a penny to 18 cents per lb.

The propylene market has been even tighter than the ethylene market. According to Steve Zinger, director of heavy olefins and elastomers for CMAI, contract prices for chemical-grade propylene have climbed to 45.0 cents per lb--higher than the ethylene price for the first time in more than 15 years, he says.

In late December, a series of outages at Shell's Deer Park complex compounded the situation in the U.S. olefins market, particularly for propylene. Shell has put ethylene and propylene customers on allocation through April and July, respectively.

Shell also declared force majeure at its ∝ -olefins and detergent alcohols units in Geismar, La., because of its internal supply problems. But a seasonal slowdown in ethylene demand softened the market in December, allowing Shell to buy enough ethylene to cover its own downstream requirements, according to Robert Chouffot, lower olefins business manager in the U.S. for Shell Chemicals.

A. Cenan Ozmeral, group vice president for petrochemicals, plasticizers, and solvents at BASF Corp., says the impact was more severe in propylene. "In the force majeure situation with Shell, ethylene wasn't a problem," he says. "Propylene was a problem."

However, unlike ethylene, in which almost all production is from ethylene crackers, propylene is also produced as a coproduct in fluidized catalytic cracking units at oil refineries. Zinger says the high propylene prices should entice refiners to extract propylene for sale to the chemical market rather than alkylate it for blending into gasoline, even with the high prices at the pump. "Right now, the incentives are on the order of 15 to 20 cents per lb versus their alternative value," he says.

The refinery output, Zinger says, plus maximum coproduct output from ethylene crackers, should put the propylene market back in balance. "We should see some correction in the second quarter and probably some stabilization after that," he says.

Chemical producers still face high oil and natural gas prices. West Texas Intermediate crude prices jumped from $34 a barrel in January 2004 to a high of $53 in October and have since remained above $40. Except for a spike to $9.00 in November, spot natural gas prices have traded between $5.00 and $7.00 per million Btu on the New York Mercantile Exchange since January 2004. This is a far cry from the historical $2.00 to $3.00 rates, but mercifully low and steady versus other challenging years in petrochemicals.

Natural gas has mostly been trading at prices below oil on a Btu basis. But high prices for coproducts such as propylene have given naphtha-based crackers an edge over the ethane-based crackers that represent about 70% of ethylene output in North America. "Naphtha-based crackers get so much additional value out of their by-products that it gives them better margins," Ozmeral says.

But the petrochemical market has strengthened to the point where energy costs no longer drive it, even for ethane-based producers, according to CMAI's Eramo. "You get different dynamics in the cycle from the peak to the trough," he says. "Prices are higher, and you are focused more on the supply-and-demand balance than you are on the cost shifts. It is not that you forget about costs, but they aren't as big a driver as they were when margins were nil," he says.

A SIMILAR EFFECT has brought the U.S. industry back to the export market, says Theo Walthie, Dow's president of hydrocarbons, energy, and ethylene oxide/glycol. "The ethylene operating rate toward the end of the year was probably on a worldwide basis one to two points away from its absolute maximum," he says. "That means that Asia, Europe, and the Middle East were running at capacity, and the only place with spare capacity was the U.S."

However, Walthie warns that the U.S. will be chased out of the export market when it softens. "U.S. ethane is still the highest cost feedstock," he says. "The U.S. is still the highest cost producer. And the U.S. still has the highest oversupply versus domestic demand. In times like these, when the world needs the supply, it is not material. But when the demand is not being required, the U.S. will again have the problem of having the highest incremental cost."

The U.S. has a much stronger position in propylene because of the massive refining infrastructure that, at the right price, is triggered into pouring out propylene, says Shell's Chouffot. "The U.S. refineries are the swing source for the global propylene market. The U.S. should be well-positioned in propylene derivatives," he says.

Despite the ethylene industry's new prosperity, producers say they won't forget North America's poor competitive position or the lessons of the last trough. At least for now, they have sworn off building new grassroots plants. "The strategy in North America will be one of energy efficiency, feedstock flexibility, and making incremental gains from existing assets and infrastructure," Eramo says. "The realization is there that North America isn't the place to build new capacity at the same rate as in the 1990s."

Val Mirosh, president of olefins and feedstocks for Nova Chemicals, says efficiency, not new capacity, was the rationale for the recently announced improvement projects at Nova's 35-year-old Corunna, Ontario, facility. "Internally, we call the project the Corunna modernization, as opposed to an expansion," he says.

The Corunna chemical complex is unique in that it has its own oil refinery that makes feedstock for its ethylene cracker. The modernization will allow the site's cracker to use more ethane-propane feedstock and less refinery feedstock. Nova will make less gasoline and other heavy coproducts, but it will gain 225 million to 400 million lb of ethylene capacity annually as well as additional propylene.

Likewise, Ozmeral says efficiency is the aim for a potential project to add a ninth furnace at BASF's joint venture cracker with Total Petrochemicals in Port Arthur, Texas. The expansion could boost ethylene output at that plant by up to 12%. However, the project would require approvals from both partners and is not likely to come onstream in fewer than two years.

Dow is investing in cheaper energy costs by taking a 15% interest in Freeport LNG Development, a 1.5 billion-cu-ft-per-day liquefied natural gas terminal proposed for Quintana Island, Texas, near Dow's Freeport, Texas, complex. Dow has signed a contract to receive a third of the output from the facility.

Walthie says the terminal will be a step in the right direction for the North American natural gas market. But it will take more than just one new terminal importing natural gas to level out high North American prices. "We are just a drop in the ocean with this new LNG terminal," Walthie says.

In the next few years, new ethylene production can come onstream in the U.S. in the form of restarts of idle capacity. Dan Smith, chief executive officer of Lyondell Chemical, recently told analysts that his company would consider recommissioning its Lake Charles, La., unit if the profit peak turns out to be protracted. He added that margins have only recently improved for plants with an ethane-propane diet.

Eramo, however, doubts Lyondell will invest the capital to restart a plant that has been idle for four years and has no derivative units without significant customer off-take agreements to ensure profitability throughout the cycle. "You have to question what strategic value there is in ethylene in Lake Charles for Lyondell," he says.

Eramo says Chevron Phillips Chemical's 650 million-lb unit in Sweeny, Texas, has a better chance of being restarted because it is part of an integrated refining and petrochemical complex.

Major ethylene projects for North America aren't out of the question. Nevertheless, Dow has delayed indefinitely its plans to replace its two closed crackers with a new one on the Gulf Coast. Walthie says Dow has little incentive to move on the project as long as it can secure ethylene contracts similar to the ones it signed when it closed the Texas plants. "We have been successful in buying ethylene from third parties," he says. "One of the options is rebuilding ourselves to a higher capacity. That remains on the table, but if we can secure a good supply from the market, we will do so."

Shintech has said it is considering a new ethylene cracker to back-integrate its planned vinyl chloride and polyvinyl chloride complex in Louisiana, but one industry source is cynical. "If I'm going to build my own ethylene-consuming assets in North America, it makes sense for me to announce that I'm going to take a good hard look at building my own ethylene unit while I'm in the middle of these negotiations for long-term ethylene supply contracts," he says.

Nova is a partner in a study in the only grassroots ethylene complex being planned in North America, a joint venture in Mexico with Mexican national oil company Pemex and other Mexican partners slated for the end of the decade.

Nova's Mirosh says negotiations are focused on feedstock contracts for the plant. "From our perspective, one of the things we have stated is that the project is very much predicated on getting an appropriately priced and advantaged feedstock," he says.

With little capacity coming onstream in the next few years, the duration of the peak in the North American petrochemical business will depend on capacity additions in other regions, says Shell's Chouffot. "You do have a number of start-ups in the Middle East and in Asia-Pacific," he says. "Because of the exports coming out of the U.S., these plants will have an effect on the cycle here as well. We are not disconnected from the global marketplace."

CHOUFFOT SAYS 2005 and 2006 should be good years, but beyond that time, industry profitability will depend on how well global growth can absorb additional capacity in the Middle East and Asia.

Advertisement

Mirosh is more optimistic: "In North America, there are no facilities being proposed that are going to make a big difference in the overall marketplace. When you see that type of situation, it's hard to envision anything absent a fairly strong collapse of the world economy that's going to impact the length of the peak."

The intensity of the peak is a little harder to pin down. BASF's Ozmeral points out that the combination of ethylene plant restarts with the idling of derivatives units may free up enough ethylene capacity to flatten out the peak.

BASF closed two ethylene oxide lines in Geismar, La., at the end of 2002. Shell is also planning to close an ethylene oxide plant in Geismar, although the unit is running long past its planned December closure. Citing high feedstock costs, Dow says it is closing a vinyl chloride/ethylene dichloride plant in Oyster Creek, Texas, by the end of this year. And BP is closing 1.1 billion lb of ∝-olefins capacity in Pasadena, Texas, by the end of this year.

In propylene derivatives, Sterling Chemicals idled its Texas City, Texas, acrylonitrile plant in February because of insufficient feedstock. The company says it is considering an overhaul at the site and may close the least efficient line there, reducing capacity by 210 million lb per year. Solutia is exiting its acrylic fibers business.

Ozmeral says such shutdowns create local surpluses in olefin capacity but don't impact overall balances. For example, when BASF shut down its ethylene oxide capacity, it was left with excess capacity from the Geismar, La., ethylene cracker joint venture it operates with General Electric and Williams Companies. BASF is now selling that output on the merchant market.

Although that ethylene cracker is generating cash, BASF may divest its share, Ozmeral reveals. "The Geismar cracker is not strategic for BASF," he says. "So BASF would certainly entertain any interested parties for our share."

The upturn in the industry cycle already has had tangible results for chemical companies. ExxonMobil Chemical's earnings increased 70% in 2004 to $3.4 billion, the firm's highest level ever. Better margins, the company says, contributed $1.5 billion to this result.

Lyondell's Equistar unit, which operates an exclusively U.S.-based olefins and derivatives business, saw operating income climb to more than $500 million last year after generating losses of about $90 million in 2003.

Although the news is good, CMAI's Eramo says U.S. petrochemical producers will require several good years to recover from the trough. "They need not only one year but probably a couple of more years to offset the 2001 through 2003 period, which was pretty bad."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter