Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

Evolving Anatomy of the U.S. Labor Force

Huge influx of women and big gains in education level overall hint at changes yet to come

by MICHAEL HEYLIN, C&EN WASHINGTON

June 13, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 24

In 1970, 43% of women age 16 and older were in the labor force. By 2004, 59% were. Over the same 1970-to-2004 period, labor force participation by men declined from 80% to 73%.

Between 1970 and 2004, the number of women in the labor force rose by 36.9 million, or 117%, while the number of men increased by 27.8 million, or just 54%.

In 1970, only 11% of women age 25 to 64 and in the labor force had completed four or more years of college. By 2004, 33% were college graduates. The parallel gain for men was from 16% to 32%.

In 2004, women held almost 47% of all jobs, including 56% of those in the category termed "professional and related," the one that includes chemists. Women also had 43% of the jobs in the science subcategory.

The median salary for all working women, as a percentage of the median for all men, rose over the past 25 years from 62% to 80%.

These are some of the highlights from "Women in the Labor Force: A Databook." Released last month by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), it is very much a just-the-facts document. The body of it runs 85 pages. Eighty-one of them are tables. It apparently provides all the factual data that those involved in the never-ending and at times contentious debate over working women and their status should need.

The report does not suggest what the role of women in the labor force should be, but it details what that role has been and what it is today. The report also give clues to what still needs to happen before there is parity between men and women in the workplace. The labor force is defined as the sum of those employed plus those unemployed but actively seeking employment.

The report is based on historic and current data from the Current Population Survey (CPS). This is a national monthly survey of about 60,000 households. It is conducted for BLS by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Although it is not an absolutely clean-cut division, the occupational categories that CPS uses can be divided into two broad groups.

One group comprises jobs in which physical strength and stamina are usually prerequisites for employment. Accounting for about 23% of all jobs, this group includes those working in what CPS characterizes as construction and extraction; farming, fishing, and forestry; transportation and material moving; installation, maintenance, and repair; and production.

In 2004, women held 15% of these jobs. This included just 2.5% of construction and extraction jobs and 4.6% of jobs in installation, maintenance, and repair. Women held a higher 30% of production jobs as they still dominate in some lighter industries, such as dressmaking.

The second group of jobs is those that are less likely, if ever, to require physical strength. These include employment in office and administrative support, sales, management, business and finance, professional and related endeavors, and the service industry.

In 2004, women held 56% of these jobs. Their share ranged from 37% of the management category to 76% of those in office and administrative support.

A closer look at women's equally large--56%--share in the professional and related job category confirms the traditional numerical dominance of women in the education and health care professions with 73% of the jobs in both.

In both of these fields, however, women still have a way to go to achieve the higher paying ranks. For instance, their share of teaching jobs drops from 98% at the kindergarten level to 46% at the postsecondary school level. At four-year colleges and universities, it is lower still. In health care, only 22% of dentists and 29% of physicians and surgeons are women, as are 92% of nurses and about 77% of clinical laboratory, diagnostic, and support technicians.

Such stratification still exists in the legal profession. According to BLS, women hold 49% of the jobs in the field. But this share is made up of 29% of the lawyers; 57% of judges, magistrates, and other judicial workers; and about 86% of the paralegals, legal assistants, and support personnel.

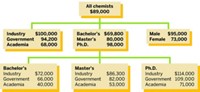

Women's 43% share of jobs in the life, physical, and social sciences category includes two-thirds of psychologists, 53% of what BLS defines as medical scientists, 45% of biological scientists, and a third of chemists and chemical technicians.

The advance of the median salary for all working women from 62% of the median for all men in 1979 to 80% in 2004 is undeniable evidence of the progress women have made in the labor force.

For some occupations, this percentage is even higher for 2004. For instance, the median salary of women in the sciences is 87% that of the men's. For other areas, the figure is much lower, including only 54% for legal occupations, 72% for management jobs, and 76% for education. These lower numbers largely reflect the continued relative dearth of women in the higher paying positions.

Women in the labor force have long been developing an educational advantage over men. Of women workers in the 2004 labor force age 25 to 64, 63% had some college or were college graduates, 29% were high school graduates, and nearly 8% had less than a high school diploma. For men, the corresponding breakdown is 58%, 31%, and 12%.

This edge for women will continue to grow. Women now earn 57% of all bachelor's degrees. Among 2004 high school graduates, 72% of young women enrolled in college compared with 61% of young men.

Apparently, parity in employment will never be a 50:50 split between men and women in all job categories.

In spite of the legendary success of "Rosie the Riveter" and her female colleagues in World War II in demonstrating that women can handle heavily physical jobs, such occupations will remain male dominated for the foreseeable future. The availability of such jobs may be a factor resulting in a lower percentage of men, compared with women, going to college.

The converse of this situation is that the increasingly superior education of women in the labor force will ensure their continued numerical majority role in the nonphysical-labor job market. Also male-female salary disparities should gradually further decline as the better educated cadre of women entering the labor force in recent years moves up through the ranks.

A factor that won't change is women's unique role in childbearing and their predominant, compared with men, commitment to child rearing. Even with the great employment gains that women have been posting, their participation rate in the workforce during their prime working years--ages 25 to 54--of about 75% lags behind the rate of about 90% for men of those ages. Also in 2004, 26% of employed women usually worked part-time. Only 11% of employed men did so.

One thing is certain: Any future changes in the gender composition of the workforce cannot be nearly as radical as those that have already occurred. In 1970, with only 43% of women working, they still represented a huge untapped resource.

The participation rate for women surged to 58% by 1990. It rose much more slowly in the '90s to peak at 60% in 1999. Since then, it has declined to 59%.

The once-unused potential of women in the labor force has apparently been about tapped out. Women's participation rate will likely stay at about its current level.

In light of the indifferent performance of the total job market in recent times, the participation rate among women is more likely to continue to drift down than to post gains. Between 1970 and 2000, the combined participation rate of men and women in the labor force never declined for more than a single year. Since 2000, it has fallen for four years in a row.

DOWNLOAD THE ENTIRE DOCUMENT OF EVOLUTION OF THE U.S. LABOR FORCE

( Adobe PDF format - 1 MB )

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter