Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

A Cell's Vacuum Cleaner

Researchers solve the structure of P-glycoprotein, which kicks molecules out of cells

by Sarah Everts

March 30, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 13

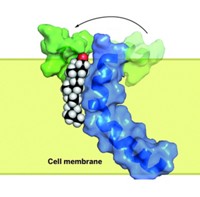

WHEN CANCERS STOP responding to chemotherapy, one of the culprits is a protein transporter that expels drugs out of diseased cells, thereby preventing the benefits of treatment. Now researchers are reporting the first mammalian X-ray crystal structure of this transporter, P-glycoprotein. The work provides a first step toward the design of drugs to thwart its action.

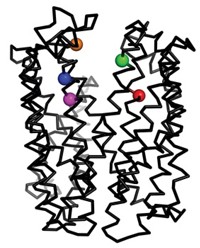

Human P-glycoprotein is often referred to as a "hydrophobic vacuum cleaner" because the membrane protein sucks up all sorts of greasy molecules—including beneficial drugs—that make their way across the lipid bilayer and sends them back outside the cell, notes Geoffrey Chang of Scripps Research Institute. He led the team of researchers that solved the structure of mouse P-glycoprotein to 3.8-Å resolution (Science 2009, 323, 1718).

Yet the pump can also do good—for example, by sitting on the placental membrane, where it protects a growing fetus from toxic chemicals. In fact, the enzyme's dual role as both an essential shield and overprotective barricade is exemplified in the blood-brain barrier, where P-glycoprotein protects the brain from harmful chemicals in blood while also frustrating drug developers by kicking out possibly useful treatments for deadly brain diseases.

"This is very exciting work," comments Stephan Wilkens, a biochemist at Upstate Medical University, in Syracuse, N.Y., who studies P-glycoprotein by electron microscopy. "Many laboratories and drug companies have been working for years on getting such a structure."

Although the structure "is a great start" for drug developers wishing to selectively block the pump, Wilkens adds, "the resolution of the side chains isn't quite good enough to do structure-based drug design yet."

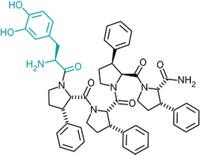

Chang's team found that the enzyme's substrate-binding pocket is a large internal cavity, open to both the membrane and the inside of a cell, and that it is full of aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids. When they solved the structure in the presence of two stereoisomers of a greasy inhibitor, they found that the isomers bound in different parts of the binding cavity, showing just how promiscuous the protein transporter is.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter