Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Breaking Up Biofilms

Microbiology: Amino acids dismantle bacterial communities

by Jyllian N. Kemsley

May 3, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 18

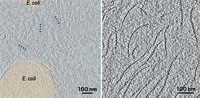

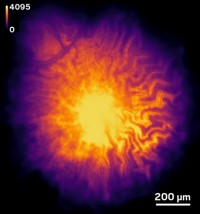

Bacteria release amino acids with the D rather than the biologically more common L stereochemistry to break up the microbial communities they live in, commonly known as biofilms, a new study shows (Science 2010, 328, 627). The findings could inspire the design of molecules that destroy troublesome biofilms.

Biofilms are aggregates of microorganisms and likely serve to protect cells from environmental threats. They have been implicated in up to 80% of microbial infections in humans, including dental plaque and chronic sinus problems. They can also cause trouble in industrial settings by corroding pipes, ship hulls, and other surfaces.

Biofilms do have a finite lifetime. As they age, they can become limited by nutrient availability and their waste products can build up, thus it becomes better for the microorganisms to return to independent life.

But “biofilm dispersal is far less studied and understood than biofilm formation,” says Ece Karatan, a biology professor at Appalachian State University who lauds the new work for its fresh insights into the mechanism behind biofilm breakup. And as bacteria Dthat reside in biofilms become resistant to existing antibiotics, the possibility of new drugs that dissolve biofilms across a variety of bacterial species is an exciting prospect, she adds.

In the new research, a group led by Richard M. Losick, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, studied Bacillus subtilis to see whether they could pinpoint a chemical signal that the bacteria use to initiate biofilm disassembly. They found that the bacteria produce four amino acids—D-tyrosine, D-leucine, D-tryptophan, and D-methionine—that can both break up existing biofilms and prevent them from forming in the first place.

A mixture of just 10 nM of each amino acid is sufficient to disrupt biofilms. Losick and colleagues believe that bacteria in the biofilm incorporate the D-amino acids into their cell walls, where they interfere with the anchoring of protein amyloid fibers that normally help hold the community together.

The researchers also found that the D-amino acid mixture can prevent biofilm formation of the common human health pathogens Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter