Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Cell-Based Screens Detect Drugs Active Against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

Preliminary results will be tested in animals infected with the MERS coronavirus

by Carmen Drahl

June 2, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 22

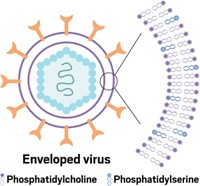

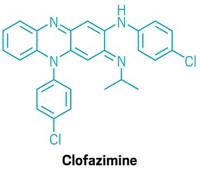

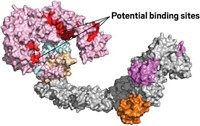

The coronavirus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) first appeared in humans in 2012. An unexplained spike in MERS cases this spring, including the first two cases in the U.S., has placed public health officials on alert. About 30% of the more than 600 confirmed infections have proved fatal. No specific treatment exists for MERS, so researchers are seeking drugs or vaccines to combat the disease in humans or its animal hosts. Two screening efforts, each of a different small library of FDA-approved drugs, have turned up potential MERS leads (Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, DOI: 10.1128/aac.03036-14 and 10.1128/aac.03011-14). One screen was carried out by Matthew B. Frieman of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and colleagues. The other screen was conducted by Eric J. Snijder of Leiden University Medical Center, in the Netherlands; Johan Neyts of Catholic University of Leuven, in Belgium; and coworkers. After confirmatory tests, the two hits the teams had in common were chloroquine and chlorpromazine. Both compounds prevent endocytosis, which is the cell’s process of engulfing outside molecules and absorbing them. This finding suggests the compounds interfere with entry of MERS into cells. The teams are preparing to verify their results in small-animal studies.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter