Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Antibody Therapies Don’t Improve Neuron Function In Mice

Neuroscience: The proteins can clear toxic amyloid-β out of the animals’ brains but don’t calm hyperactive nerve cell firing

by Michael Torrice

November 12, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 45

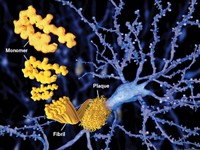

Toxic clumps of the peptide amyloid-β build up and form plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. So drugmakers have looked for ways to clear out amyloid-β, including using antibodies that bind to the peptide.

Now a study in mice suggests that these antibodies may not improve the dysfunctional activity seen in Alzheimer’s-affected neurons and may even worsen it (Nat. Neurosci. 2015, DOI: 10.1038/nn.4163).

Clinical trials of these so-called immunotherapies have yielded mixed results, with early studies reporting no improvement in cognitive function and more recent ones showing some progress.

The new mouse results “do not mean that we should stop all immunotherapy trials,” says Marc A. Busche of the Technical University of Munich, who led the study. “I think the main take-home message is that we need to better understand what these antibodies are doing in the brain.” Such information, he says, could lead to better antibody therapies.

The new study looks at the firing of neurons in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. In 2008, Busche found that amyloid-β causes neurons to fire more frequently, resulting in cells that do not function properly.

He and his colleagues, including Munich’s Arthur Konnerth, wanted to see how antibody treatments would affect this neuronal hyperactivity. “We thought what everyone thought: If you removed amyloid-β from the brain, neuronal function should improve,” Busche says. “So we were very surprised to see that this was not what was going on.”

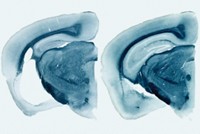

When the researchers injected one of two amyloid-β antibodies into mice genetically engineered to overproduce the Alzheimer’s peptide, they observed lower levels of amyloid-β in the animals’ brains. But when they monitored neuronal activity using two-photon Ca2+ imaging, they did not see a reduction in the hyperactivity. In fact, they saw an increase.

This neuronal dysfunction didn’t occur in normal mice injected with the antibodies, suggesting that the effect depended on interactions between the antibodies and amyloid-β. One possibility, Busche says, is that the antibodies solubilize small bits of the amyloid brain plaques called oligomers, which are known to trigger neuronal hyperactivity.

Some Alzheimer’s researchers question whether the results, observed in genetically engineered mice, are applicable to people. “While a number of clinical trials have been negative—shown no benefit—none has shown a worsening of cognitive function,” says Paul S. Aisen, a neurologist at the University of Southern California.

Busche cautions that it’s unclear whether the increased neuronal hyperactivity would necessarily lead to a worsening of cognitive abilities. There may not be a one-to-one relationship between the two, he says.

Representatives at Eli Lilly & Co. and Biogen, two companies that released clinical trial data on their antibodies earlier this year, did not wish to comment on the new study.

This article has been translated into Spanish by Divulgame.org and can be found here.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter