Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Liquid metal solidifies new method for growing semiconductors

eGaIn enables easy electrochemical route to high-quality germanium films

by Matt Davenport

June 5, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 23

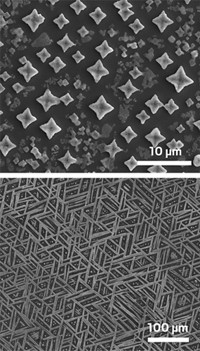

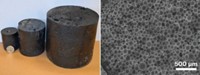

Growing high-quality semiconducting crystals isn’t easy. It typically takes high temperatures, highly reactive precursors, and extensive equipment. Electrochemical deposition could simplify the process, but attempts using conventional solvents yield “amorphous junk,” says Stephen Maldonado of the University of Michigan. Working with colleagues at Ohio State University, Maldonado’s team has found that a liquid metal can help electrochemistry conquer this shortcoming (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b01968). The researchers started with an aqueous germanium oxide solution and introduced eutectic gallium-indium, or eGaIn. This liquid metal forms an intermediate layer between the solution and a solid silicon substrate. Germanium reduced in water can cross the interface into the eGaIn and migrate to the silicon. By tuning the thickness of the eGaIn layer, the researchers ensure that germanium accumulates into a high-quality, crystalline film. This low-cost, benchtop approach works at room temperature, unlike conventional semiconductor growth, Maldonado says. The group is exploring liquid metal solvents further, hoping to inspire others to rethink how they make semiconductor circuits and devices.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter